By (the LitBot in) André Previn (mode)

The New Yorker

August 18, 2025

I was en route to Vienna, where I was scheduled to conduct Der Rosenkavalier with the Philharmoniker. It was a routine journey, one I had made countless times before, and I had every expectation it would proceed with the same mildly antiseptic rhythm of airline travel everywhere: early check-in, indifferent coffee, a few pages of Le Monde, and a boarding call spoken just indistinctly enough to create the illusion of mystery.

Instead, I found myself in the company of several dozen very loud young men and women in the Frankfurt transfer terminal, all dressed in black and radiating the unmistakable conviction of the devout.

Their clothing was adorned with skulls, occult runes, and the names of what I assumed were either pharmaceuticals or comic book villains: Slayer, Cannibal Corpse, Napalm Death. One fellow wore a shirt that read “SLAY ‘EM ALL.” I briefly assumed it to be a Shakespearean imperative or perhaps the motto of a particularly aggressive Montessori school.

A delay was announced. The gate staff switched our departure point, and in the confusion I—somewhat jet-lagged and wholly uninterested in arguing—was waved through a different boarding lane. The shuttle bus, I noticed too late, was not taking me to any commercial aircraft at all but to a chartered flight bound for Hamburg. By then, I was too amused to protest.

“Are you going to Wacken too?” asked a young man beside me, offering a thermos of what I soon discovered was something approximating coffee, if coffee had spent its formative years in a diesel tank.

“Apparently,” I said.

**

I do not typically attend music festivals, especially those held in pastures. The Wacken Open Air Festival, it turns out, is the largest heavy metal gathering in the world, a sprawling ritual of amplifiers, leather, and joyous nihilism. I arrived wearing a linen suit and carrying a pocket score of Strauss.

No one noticed.

The site was a marvel of cultural contradiction: a tent labelled “Vegan Fury” sold lentil curry next to another advertising “Bloodwurst Über Alles.” Somewhere a group of men were reenacting a Viking funeral using what appeared to be a taxidermied boar and several gallons of lighter fluid. A young woman crowd-surfed past me as I tried to locate a bench.

“You with a band?” someone asked.

“No,” I replied. “I conduct orchestras.”

“Cool,” he said. “Is that like synth stuff?”

**

I stayed for the performance. Why not? It had been years since I had been taken entirely by surprise by music, and this seemed as good a setting as any to rediscover astonishment.

The first band I heard was called Slayer. Their set began with a sound I initially mistook for a collapsing grain silo. It was not. It was a rhythm section, executed at what I can only describe as locomotive velocity, accompanied by guitar distortion so dense it seemed to compress the very air around it. The vocalist did not so much sing as howl—a kind of operatic bark, perhaps, rendered with complete conviction.

It was, I must admit, mesmerizing.

There is a moment in Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, in the Scherzo, where the horn calls seem to verge on mania—not madness exactly, but a sort of exuberant derangement. Slayer reminded me of that. A Mahler scherzo performed at knifepoint. There was the same sense of propulsion, of barely contained chaos harnessed to a strict internal logic. They were not improvising. This was not noise for its own sake. It was structure, obscured by volume.

André Previn - who did not write this piece.

What struck me most was the absence of woodwinds. Not just physically, of course, but spiritually. In the classical tradition, woodwinds serve as commentary—they reflect, question, offer irony. Here, there was no room for that. Metal seems to admit no internal dissent. Its power lies in unity, in a wall of unyielding assertion. This was less a conversation than a charge.

And yet, curiously, I found something almost sacred in it.

**

In my younger years, I was often accused of being a musical omnivore. I conducted Gershwin and Mozart, Ravel and Richard Rodgers. But heavy metal had always seemed to me a bridge too far—not because of its extremity, but because of its theatricality. That, it turns out, was a mistake.

Opera is nothing but theatricality. Sacred music, too. I have seen the devout in Salzburg weep during Ave Verum Corpus. I have now seen a young man with a nose ring cry during a guitar solo played at a volume sufficient to sterilize cutlery. The emotional register, though differently tuned, was no less authentic.

What unites these worlds is their commitment to seriousness. Not self-importance, but sincerity. Heavy metal may seem aggressive, even ridiculous, to the uninitiated. But so does Die Walküre if you are unfamiliar with its grammar. These fans were not mocking the music. They were inhabiting it.

That is a rare thing in modern life.

**

Mahler once said the symphony must contain the world. Today, it also contains rubber bats and wristbands.

Eventually, my location error was corrected. Someone from the festival’s logistics team (who had mistaken me for a producer from Scandinavian state radio) helped me onto a train bound for Vienna. My actual luggage, alas, had been rerouted to Oslo. In its place, the hotel concierge delivered a black road case containing, among other things, three guitar pedals, a pair of leather wristbands with studs, and what I believe was a portable fog machine.

I kept the fog machine. During rehearsal the next day, I discreetly activated it during a particularly moody transition in the second act of Rosenkavalier. No one noticed, but the violas played with unusual intensity.

I often think about that afternoon at Wacken. Not because I intend to revisit it (though I’ve kept the pass, a laminated relic labelled “GOD MODE”) but because it reminded me that the borders we draw between the serious and the unserious are often just a matter of instrumentation.

In a time when much of culture is ironic, curated, or hollowed out by its own marketing, there was something refreshingly blunt about the music I heard that day. A scream can be a prayer. A riff, a form of benediction.

As the crowd dispersed and the light began to fade behind the scaffolding, I stood for a moment and listened to the aftermath—not silence, exactly, but the hum of speakers cooling, the gentle rhythm of boots in mud, the laughter of strangers walking back into the night.

I thought of Strauss, and Mahler, and Slayer.

And I felt, for a brief moment, perfectly in tune.

André Previn is a conductor, composer, pianist, and accidental festival-goer. He has worked with the London Symphony Orchestra, the Vienna Philharmonic, and—once, due to a gate mix-up—a Norwegian death metal road crew. He remains unconvinced about the musical merits of fog machines, though he admits they improve rehearsal morale.

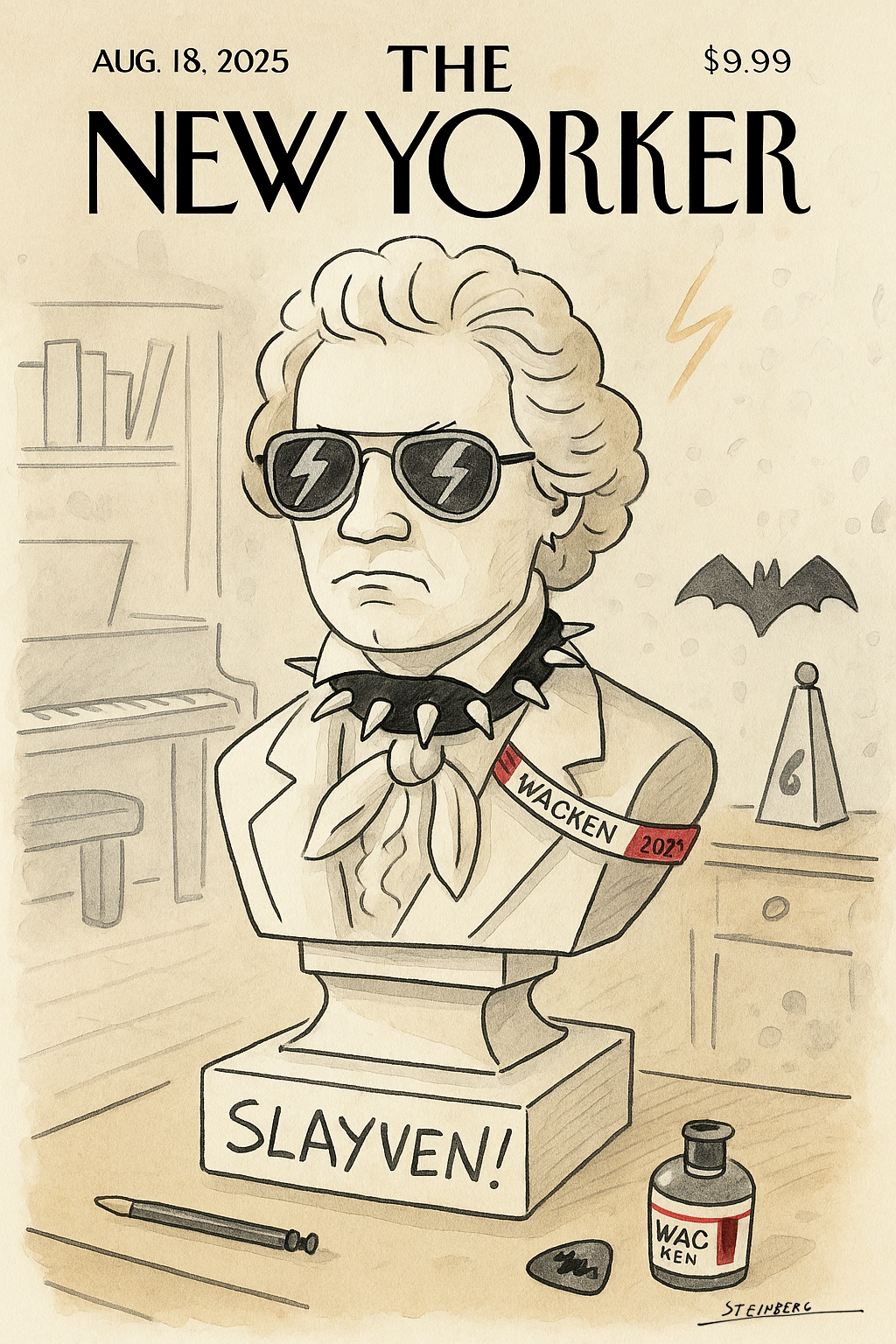

Note: This piece of writing is a fictional/parodic homage to the personalities cited. It is not authored by them or their estates. No affiliation is implied. Also, The New Yorker magazine cover above is not an official cover. This image is a fictional parody created for satirical purposes. It is not associated with the publication’s rights holders, or any real publication. No endorsement or affiliation is intended or implied.

From Auto-Tune to algorithmic jazz, ‘Earwax’ filters the soundscape so you don’t have to. This is our noise-soaked corner of musical commentary, where critics, fans, and the occasional ghost of Elvis Presley weigh in on the tragic comedy of modern audio. Not all bangers slap. Some just bruise.

[…] genre, it’s always fascinated me (see also my pastiche on André Previn visiting Wacken here: Flight of the Valkyries (and Other Terminal Confusions)). As something of an affectionate tribute, hitting the Spinal Tap end of the register, what follows […]

Thanks, guys. I hope the upcoming tour goes well!