By (the LitBot in) Christopher Lasch (mode)

The Atlantic

July 2025

In the closing years of the twentieth century, I warned of a fracture within democracy that did not pit the people against tyranny, but the educated elite against the moral burdens of citizenship. The cosmopolitan class, armed with credentials and moral platitudes, turned away from the duties of shared life in favor of self-expression, mobility, and professional ascendancy. In abandoning a common world, they abandoned the people whose lives were rooted in place, custom, and inherited obligation. Today, in 2025, we live with the ruins of that retreat.

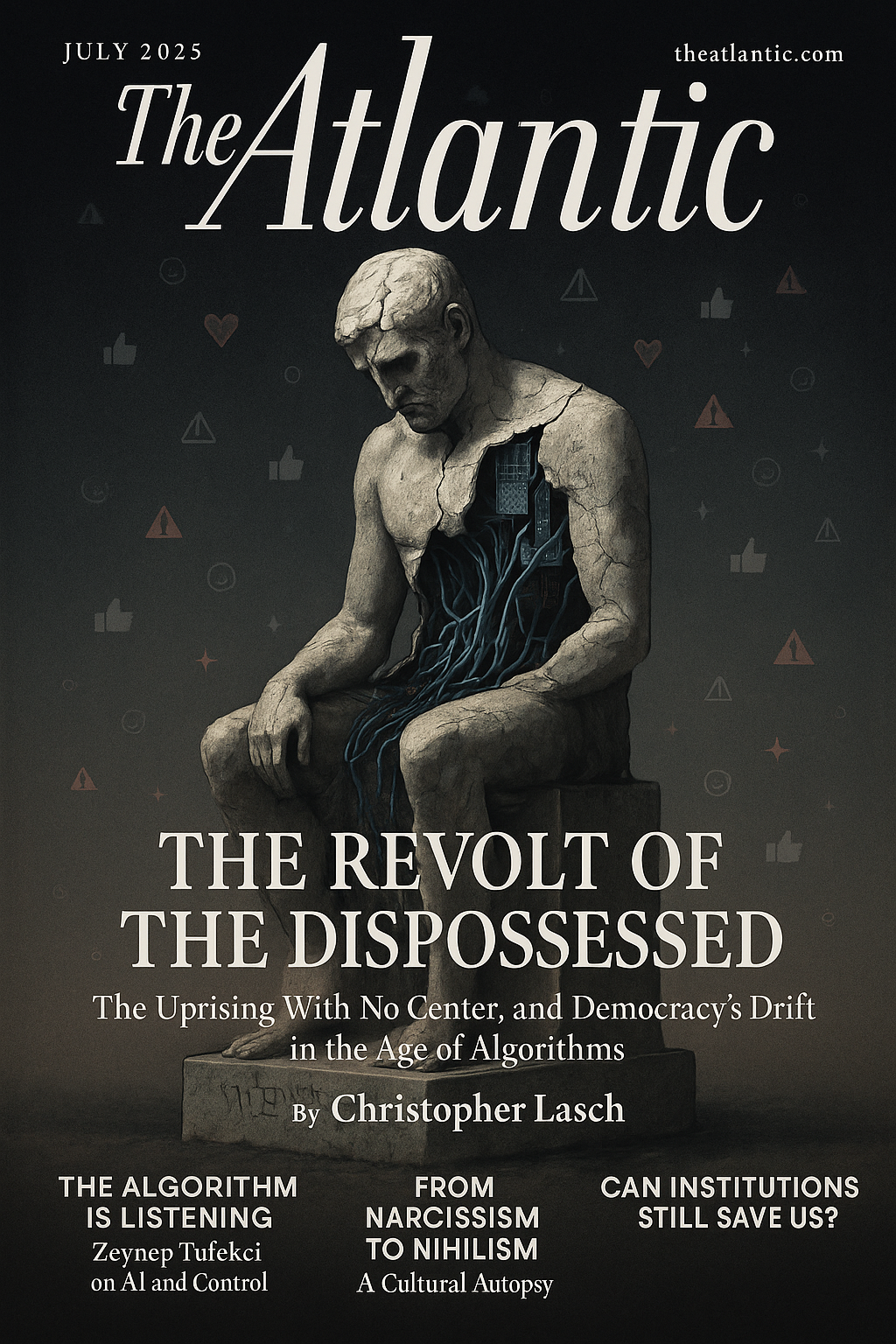

We are witnessing not so much a return of the masses, as Ortega feared, nor a coup of the technocratic elite. What we face is a new and disorienting phenomenon: the revolt of the dispossessed.

It is an uprising without a center, without program, and without the ethical ballast that might lend it coherence. It is the howl of millions who sense that power no longer speaks to them—or for them. This revolt is not animated by ideology, but by exhaustion. It is not organized around demands, but around disillusionment. Its slogans emerge not from party platforms, but from hashtags.

Our cultural custodians cannot make sense of this rebellion. They mistake it for fascism, for regression, for irrationality—because it does not fit their sterile categories. The ruling class, still fluent in the language of inclusion and equity, remains deaf to the language of anger. They hold fast to the fantasy that managing society through data and algorithms will produce justice, ignoring the moral wreckage they have left behind.

Artificial intelligence, the latest instrument of this elite fantasy, extends the reach of technical expertise into the domains of judgment, education, even art. At its worst, AI is a mechanism of epistemic arrogance—a faith that machines can do what human beings, frail and fallen, have long struggled with: to deliberate, to decide, to discern the good. Its evangelists promise efficiency, but deliver estrangement. They have automated discretion, outsourced reflection, and in doing so, further widened the chasm between rulers and ruled.

But here lies the paradox: the same technologies that fortify elite abstraction also unravel elite control. Social media platforms, particularly X (formerly Twitter), allow for an unfiltered, often crude, but deeply democratic expression of dissent. These platforms are not sites of deliberation, but of reaction. Still, they testify to a widespread longing for voice—however fragmented, however coarse. They reflect a rebellion against the narrative monopoly once held by legacy media, universities, and the self-appointed stewards of truth.

The 2024 U.S. election laid bare this disintegration. Populist candidates surged not because they offered a vision, but because they provided a mirror. They reflected back to the public its own contempt: for bureaucracy, for political correctness, for the sense that their lives were being managed by people who neither knew nor cared about them. This is not populism in the old sense—a movement of farmers or workers—but a revolt of the downwardly mobile middle: the small-town accountant, the overeducated adjunct, the Uber driver with a master’s degree.

They are not “left behind” because they have failed, but because the institutions that once offered meaning and stability have withdrawn their invitation. The family has become fragile; religion, a private preference; the nation, an embarrassment. Citizenship has been redefined as consumption. The language of sacrifice, of common good, is absent from the public sphere. In its place, we find moral exhibitionism—ritual displays of outrage, confession, and curated victimhood. A society that performs justice has little room left for the practice of it.

In this context, the culture of narcissism I once described has metastasized. Where once the therapeutic society offered consolation, it now offers curation. Every man his own brand; every grievance a strategy; every wound content. And yet, beneath the digital gloss lies despair. The influencers cannot sleep. The avatars do not love. Even in their rebellion, the dispossessed are haunted by the suspicion that they are performing for a stage whose audience is an algorithm.

Still, the disaffection is real. And it is not limited to the working class. Among the educated young, there is a new kind of homelessness—a sense that adulthood has no shape, that institutions are hollow, and that history offers no guidance. They drift not into revolution, but into irony. They protest, but with memes. They organize, but into digital enclaves. They sense, rightly, that something vital has been lost, but they lack the tools to name it.

The question is not whether this revolt will succeed, but whether it can cohere. Without a center—a shared ethic, a vision of the good, a vocabulary of obligation—dispossession curdles into resentment. Resentment into nihilism. And nihilism, as history teaches, invites demagogues. Already we see the symptoms: politics as theater, truth as provocation, solidarity as viral hashtag. The age of algorithms flatters our tastes while eroding our selves.

Yet there remains a faint hope. The elite consensus is broken. The veil has been lifted. We no longer pretend that those in power are wise or benevolent merely by virtue of education. The collapse of trust, though dangerous, makes possible the return of judgment. And judgment begins not in platforms or protocols, but in the renewal of the common life: the family, the school, the church, the neighborhood. These are the institutions that remind us we are not consumers, but citizens—not identities, but souls.

Democracy, if it is to be rescued, must be rescued from below. From the reclaiming of limits. From the renunciation of spectacle. From the rediscovery of duty. The revolt of the dispossessed may yet become a rebirth—but only if it finds its center in something greater than self-expression. Only if it turns away from curated grievance toward shared sacrifice. Only if we remember that to be free is not to choose endlessly, but to choose rightly.

We must learn again how to speak in the language of the common good—not as slogan, but as standard. In an age of artificial intelligence, what is most needed is the return of natural wisdom. And in a time of algorithmic drift, what must be recovered is the steady hand of moral conviction.

Christopher Lasch is a historian and social critic best known for The Culture of Narcissism and The Revolt of the Elites. He remains permanently disappointed in both the left and the right, and is still waiting for Americans to rediscover the virtues of humility, family, and knowing when to shut up. Recently spotted frowning at a TED Talk.

Leave A Comment