By Anton Verma

Jakub Novák slumped in a creaky chair in his Prague flat, a half-empty Pilsner sweating on the table. At twenty-six, he felt like he’d aged a century. His grandfather’s stories of Václav Havel—poet, dissident, president—echoed in his mind like a taunt. Havel had toppled communists with truth and wit; Jakub’s own plays, scathing satires of Czech corruption, barely drew a crowd at the Divadlo Na Prádle. His journalism gigs paid less than a tram driver’s wage, and the politicians he exposed just smirked from their billboards. Liberals, conservatives, populists—they were all the same: slick suits, empty promises, and scandals swept under the Charles Bridge.

“What a joke,” Jakub muttered, scrolling X on his phone. The latest presidential polls showed a neck-and-neck race between a media-savvy populist, Tomáš Vlk, who railed against ‘Brussels elites,’ and a sanctimonious liberal, Eva Černá, preaching human rights while cozying up to oligarchs. Jakub’s grandfather had marched for freedom; now, the Czech Republic felt like a circus with clowns on the take and no ringmaster.

That’s when the idea hit him, as absurd as a Kafka novel: if politics was a farce, why not run a candidate to match? Not a person, but a golem—the mindless clay creature from Prague’s Jewish folklore. It’d be the ultimate protest, a walking middle finger to the entire system. He’d read about Rabbi Loew’s golem in school, a protector born from Vltava clay. Surely, some mystic in one of Prague’s older quarters could help him pull it off.

**

In a damp cellar beneath Josefov, Růžena Katzová, an elderly Kabbalist with eyes like smoked glass, listened to Jakub’s pitch. Her shelves groaned with crumbling texts, and a faint whiff of river mud hung in the air. “A golem for president?” she said, her voice dry as parchment. “You mock the sacred to spite the profane.”

Jakub shrugged. “The sacred’s dead, and the profane’s running the country. Help me make a point.”

Růžena’s lips twitched—amusement or disdain, he couldn’t tell. She’d spent decades preserving the spiritual heritage of Prague’s Jewish Quarter, but she harboured her own grudges. A corrupt politician had once seized her family’s property, and destabilising the system appealed to her more than she let on. “Very well,” she said. “But a golem is no toy. It obeys, but it carries the weight of its maker’s intent.”

They worked by candlelight, kneading clay from the Vltava’s banks, chanting Hebrew verses from a manuscript Růžena claimed came from the Old New Synagogue. The golem took shape: getting up to seven feet tall, vaguely humanoid, with a featureless face and limbs like sculpted stone. Jakub scrawled emet (truth) on its forehead, per tradition. He named it Hlina—clay, simple, ironic. “Perfect,” he grinned. “It’s got more charisma than Vlk already.”

**

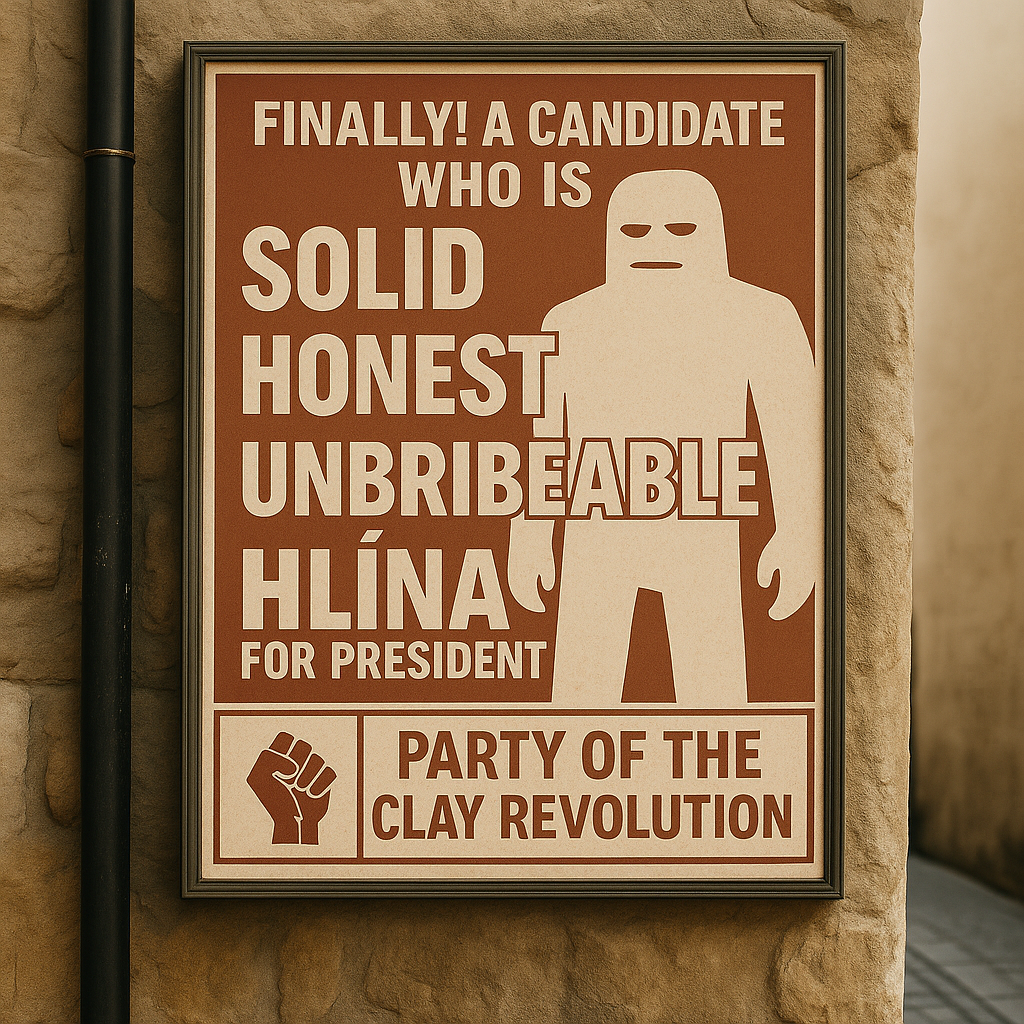

Jakub founded the Party of the Clay Revolution (PCR), a name dripping with mockery of both communist acronyms and revolutionary clichés. With no money in his savings, he turned to X, posting grainy videos of Hlina lumbering through Old Town Square, captioned:

Hlina for President: Solid, Honest, Unbribeable.

He leaned into the absurdity, tweeting manifestoes like, “No scandals, no speeches, no soul—vote PCR!” To his semi-shock, the posts gained some traction. Disillusioned Czechs, from Prague hipsters to rural pensioners, shared memes of Hlina captioned “Finally, a candidate who won’t lie—because he can’t speak.”

He recruited Marek, a cynical marketing dropout, as the ‘campaign manager.’ Marek saw the golem as a TikTok stunt, not a cause. “This is gold,” he said, filming Hlina staring blankly at a tram. “People hate politicians. A clay slab’s the ultimate outsider.” Jakub didn’t care about Marek’s motives; he just wanted noise.

But the system pushed back.

The presidential debate organisers banned Hlina, not that the debate had even been on Jakub’s radar, citing a rule that only candidates polling above 5% in ‘recognised’ polls could participate.

A week later, after Hlina nudged up to 8% in an independent poll—fuelled by X buzz and a minor backlash to the ban. Within a couple of days, the poll numbers were repeated in enough polls to meet the threshold. But they still refused to let Hlina participate, claiming a golem wasn’t a ‘natural person.’ Jakub decided he was livid. This was his protest, his performance art, and they were censoring it.

Enter Petra, a barista from Brno who’d seen Jakub’s posts. Fed up with the same political circus, she launched a GoFundMe titled ‘Let the Golem Speak!’ It raised 200,000 CZK in a week, enough to hire a scrappy lawyer. The case hit the courts, with Jakub arguing that excluding Hlina violated free expression. The media lapped it up, dubbing it ‘The Golem Trial.’ To Jakub’s astonishment, the court ruled in his favour, citing a technicality about candidate eligibility.

Hlina was in.

**

The debate was held in a sleek Prague studio, Prague Castle looming through the windows. Jakub led Hlina in like a zookeeper guiding a gorilla, positioning the golem at its podium. The audience tittered; Vlk sneered, Černá adjusted her glasses. Hlina stood silent, its clay bulk radiating an eerie gravitas.

The moderator, visibly uncomfortable, began.

“First question: How will you address EU regulations stifling Czech businesses?” Vlk ranted about sovereignty; Černá waxed poetic about cooperation. Hlina said nothing. Jakub, seated in the front row, bit his lip to keep from laughing.

Then, surprisingly early in the piece, came the culture war question: “What’s your stance on transgender rights?” Vlk scoffed, “I won’t let that nonsense infect Czechia.” Černá countered, “It’s about human dignity.” Jakub couldn’t resist. He leapt up, shouting, “Why don’t you ask Hlina? It’s the only genuinely non-binary candidate in the race!” The crowd roared—half laughter, half outrage. Security hustled Jakub and Hlina out mid-debate, the golem’s heavy steps echoing.

In the wash-up, online exploded. Clips of Jakub’s quip went viral, and polls declared Hlina the debate’s ‘winner’ by a wide margin. Its silence was hailed as ‘refreshing’ compared to Vlk’s bluster and Černá’s platitudes. Hlina’s polling soared to 20%, trailing the frontrunners but closing fast. Mainstream outlets like ČT1 invited Jakub for interviews. He played along, treating each appearance as theatre. “Hlina’s platform?” he’d say. “It stands for absolutely nothing, just like the rest of them. But it’s totally upfront about it. You want a do-nothing but honest candidate. Hlina’s your man. Or woman. Or thing. Today it identified as a shopping trolley.” Audiences ate it up, mistaking his sarcasm for sincerity.

Jakub never planned for any of this. He’d wanted to scream into the void, not appear on television. The system was rotten—populism in the countryside, apathy in Prague, EU bureaucrats meddling from afar. Hlina was satire, not a solution. Yet the more he mocked, the more people projected their hopes onto the golem. Rural voters saw it as a rebuke to urban elites; students saw it as a seven-foot-high mooning of the establishment. Even his grandfather’s old dissident friends sent emails: “This is Havel’s spirit reborn.”

Jakub cringed. Havel’s ‘living in truth’ was about integrity, not clay puppets.

Růžena wasn’t surprised. Over tea in her cellar, she said, “You gave Hlina life, but the people give it meaning. Be careful what you’ve unleashed.” Jakub waved her off. “It’s just a stunt.”

But her words lingered.

**

Election night was a blur.

Jakub watched the results in a Malá Strana pub, Marek chugging beer beside him. It was a good excuse for a party in his mind.

But when ČT1 announced Hlina’s victory—35% of the vote, edging out Vlk and Černá—Jakub nearly choked on his knedlíky. (This wasn’t supposed to happen.)

The pub erupted in cheers and jeers.

X lit up with hashtags: #HlinaPrezident, #ClayRevolution.

Petra’s GoFundMe donors claimed credit.

Marek was already designing Hlina hoodies.

In all the hubbub, Jakub quietly exited the building with the new President of the Czech Republic, silent as ever, and stumbled onto the Charles Bridge, the Vltava glittering below. Hlina’s silhouette dwarfed him as he looked out over the waters at Prague’s spires glowing under the moon.

He’d meant to expose the joke of politics, but the punchline had won.

Růžena’s warning echoed.

The EU had already sent a text, demanding a meeting. Vlk was calling for a recount. Černá was calling for calm and understanding.

Jakub stared at Hlina’s blank face, searching for answers.

“What the hell happens now?” he muttered.

But the golem didn’t reply.

© Anton Verma, 2025

Leave A Comment