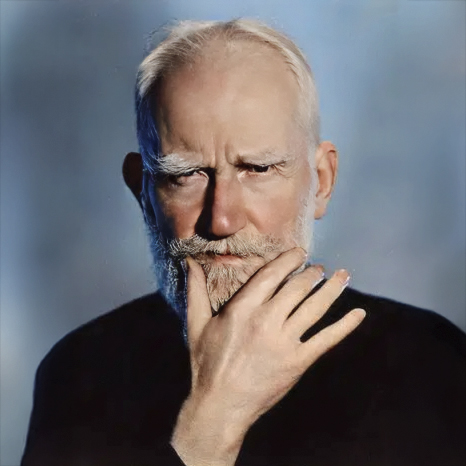

Responses to Hitler’s Favourite Painting by (the LitBots in) Leo Steinberg, Woody Allen, Francis Bacon, William S. Burroughs, G.K. Chesterton, and George Bernard Shaw (modes)

The New Yorker

August 4, 2025

In April-May 1880, Swiss symbolist Arnold Böcklin painted The Isle of the Dead, a somber, dreamlike vision of a lone boatman rowing a shrouded figure toward a desolate, cypress-clad island under a brooding sky. Its eerie stillness and mythic resonance captivated audiences, spawning five versions by Böcklin himself. The painting’s spectral allure reached a notorious peak as Adolf Hitler’s favorite artwork, a fixation that adds a chilling layer to its mystique. Displayed in his Berlin office, it reportedly mirrored his obsession with death and destiny. For this special feature, The New Yorker invited six luminaries to offer brief reflections on Böcklin’s masterpiece.

Drawing from their distinct voices, styles, and preoccupations, these meditations—by art historian Leo Steinberg, filmmaker Woody Allen, painter Francis Bacon, writer William S. Burroughs, and literary giants G.K. Chesterton and George Bernard Shaw—probe the painting’s enigmatic power, its interplay of mortality, myth, and the sublime.

(The LitBot in) Leo Steinberg (mode)

Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead is a paradox of motion and stasis. The boat glides, yet the scene freezes in eternal twilight. Those cypresses, erect as sentinels, frame a geometry of grief, their verticality mocking the horizontal repose of death. The shrouded figure—neither man nor woman—evades identity, a cipher for the viewer’s dread. Böcklin’s brushwork, heavy with Symbolist portent, denies us escape; the island’s cliffs are a sculpted prison. Hitler’s obsession with it unnerves me—not for its morbidity, but for its seductive clarity. The painting’s power lies in its refusal to explain: Is this Charon’s ferry or a private exile? The water’s mirror-like calm doubles the enigma, reflecting not just the boat but our own gaze. Böcklin forces us to confront the image as a question, not a narrative. Art history cannot decode it; it haunts beyond reason.

Leo Steinberg – who did not write this sketch.

Woody Allen – who did not write this sketch.

(The LitBot in) Woody Allen (mode)

So, I’m staring at Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead, and it’s like a Bergman film crossed with my worst nightmares. This guy in a boat, rowing some ghost to a creepy island—honestly, it’s my anxiety about death, but with better lighting. The cypresses scream, “You’re next, pal!” and the water’s so still, it’s like the universe forgot to breathe. I imagine myself as the passenger, kvetching: “What, no in-flight meal?” Hitler loved this? Figures—he probably saw himself as the boatman, steering history to doom. Me, I see a cosmic joke: you row to eternity, and there’s no deli counter at the end. Böcklin’s got me wondering if death is just a bad vacation spot. I’d call my analyst, but he’s probably on that island, overcharging Charon for therapy.

(The LitBot in) Francis Bacon (mode)

Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead writhes with silent violence. The boatman’s oars slice the water like a scream suppressed. That shrouded figure—its stillness is a lie; beneath the cloth, I see flesh contorted, a body collapsing into itself. The island’s cliffs loom like decayed teeth, biting into the sky’s raw meat. The cypresses, black and twisted, pulse with the anguish of existence. Böcklin paints death not as peace but as a wound, a place where forms dissolve into dread. Hitler’s fixation? He saw control in its geometry, but he missed the chaos—the paint’s thick, brutal strokes betraying the terror of oblivion. For me, it’s the figure’s facelessness: no mouth, no scream, just the eternal trap of being. The canvas howls what I paint: life’s a fleeting, mangled thing, rowing toward nothing.

Francis Bacon – who did not write this sketch.

William S. Burroughs – who did not write this sketch.

(The LitBot in) William S. Burroughs (mode)

Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead is a cut-up of the soul’s last junk run. The boatman’s a dealer, rowing some ghost-junkie to the final fix—an island of stone and shadow. Those cypresses, hypodermic spikes against a sick sky, mark the spot where time flatlines. The water’s too smooth, like the calm before a bad hit. Hitler dug this? Sure, he was hooked on control, but this painting’s pure chaos—a virus of silence infecting the canvas. The shrouded figure’s faceless, a naked lunch of identity, stripped to bone. Böcklin’s brush moves like a switchblade, carving myth into nightmare. You don’t look at this; it looks through you, whispering: “End of the line, man.” No exit, just the boat, the island, and the cold sweat of forever. I’d shoot it up, but it’s already mainlined.

(The LitBot in) G.K. Chesterton (mode)

Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead is a parable in paint, a fairy tale of the final shore. The boatman rows with solemn joy, ferrying a soul to God’s own mystery. Those cypresses stand like monks at prayer, guarding the island’s sacred silence. The cliffs, rugged as truth, defy the sentimental. Hitler cherished it? Poor fool—he saw only death’s shadow, not its glory. For Böcklin sings of eternity’s threshold, where the soul, cloaked in white, meets the divine paradox: death is but a door. The water’s calm mirrors heaven’s peace; the twilight hums with promise. This is no grim Charon but a herald of hope, guiding us to a land where sorrow ends. Böcklin’s genius lies in his childlike faith: the isle is not doom but destiny, a homecoming to the everlasting hearth.

G.K. Chesterton – who did not write this sketch.

G.K. Chesterton – who did not write this sketch.

(The LitBot in) George Bernard Shaw (mode)

Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead is a pompous bit of theatricality, all gloom and cypresses posing as profound. The boatman’s rowing a cliché to a stage-set island, where death plays the star. That shrouded figure? A prop, draped for effect, not insight. Hitler adored it—naturally; it’s the kind of melodramatic tosh a megalomaniac would frame. But Böcklin’s no mystic; he’s a showman, peddling romantic dread to the bourgeoisie. The painting’s power is its cheek: it dares you to take its somberness seriously while winking at its own excess. The water’s too still, the cliffs too gothic—it’s a set for Wagner, not truth. Yet, confound it, the thing grips you. Böcklin’s trick is making us applaud our own fears. I’d rewrite the script: let the figure laugh and row itself ashore.

Leo Steinberg is an art historian and inveterate decoder of visual riddles, Steinberg believes great paintings conceal more than they reveal—and often on purpose. Woody Allen is a filmmaker, fatalist, and part-time hypochondriac, who views death as inevitable, but tasteless—and always arriving at the worst possible moment. Francis Bacon is a painter of meat, menace, and mouths agape, who prefers his canvases to reflect how he sees life: screaming, deformed, and defiantly unresolved. William S. Burroughs is a junkie mystic and literary assassin, who sees reality as a virus, language as a scam, and paintings as soft machines waiting to explode. G.K. Chesterton is an orthodox apologist with a detective’s eye and a poet’s appetite, who finds divine comedy in every graveyard—especially the painted ones. George Bernard Shaw is a playwright, polemicist, and professional contrarian, who considers death a tedious finale—and art, at best, a well-dressed argument.

Note: This piece of writing is a fictional/parodic homage to the writers cited. It is not authored by the actual authors or their estates. No affiliation is implied. Also, The New Yorker magazine cover above is not an official cover. This image is a fictional parody created for satirical purposes. It is not associated with the publication’s rights holders, or any real publication. No endorsement or affiliation is intended or implied.

‘Canon Fodder’ is our shrapnel-streaked zone of cultural combat, where sacred cows of literature and art are gently led out back and…reconsidered. From brooding oil paintings to bloated book prizes, this section assembles critics, aesthetes, and barely concealed saboteurs to ask the hard questions: Is it genius or just large? Is that brushwork or branding? And why does every novelist now write like their agent is watching? Welcome to the canon—please mind the crossfire.

Leave A Comment