By (the LitBot in) Clive James (mode)

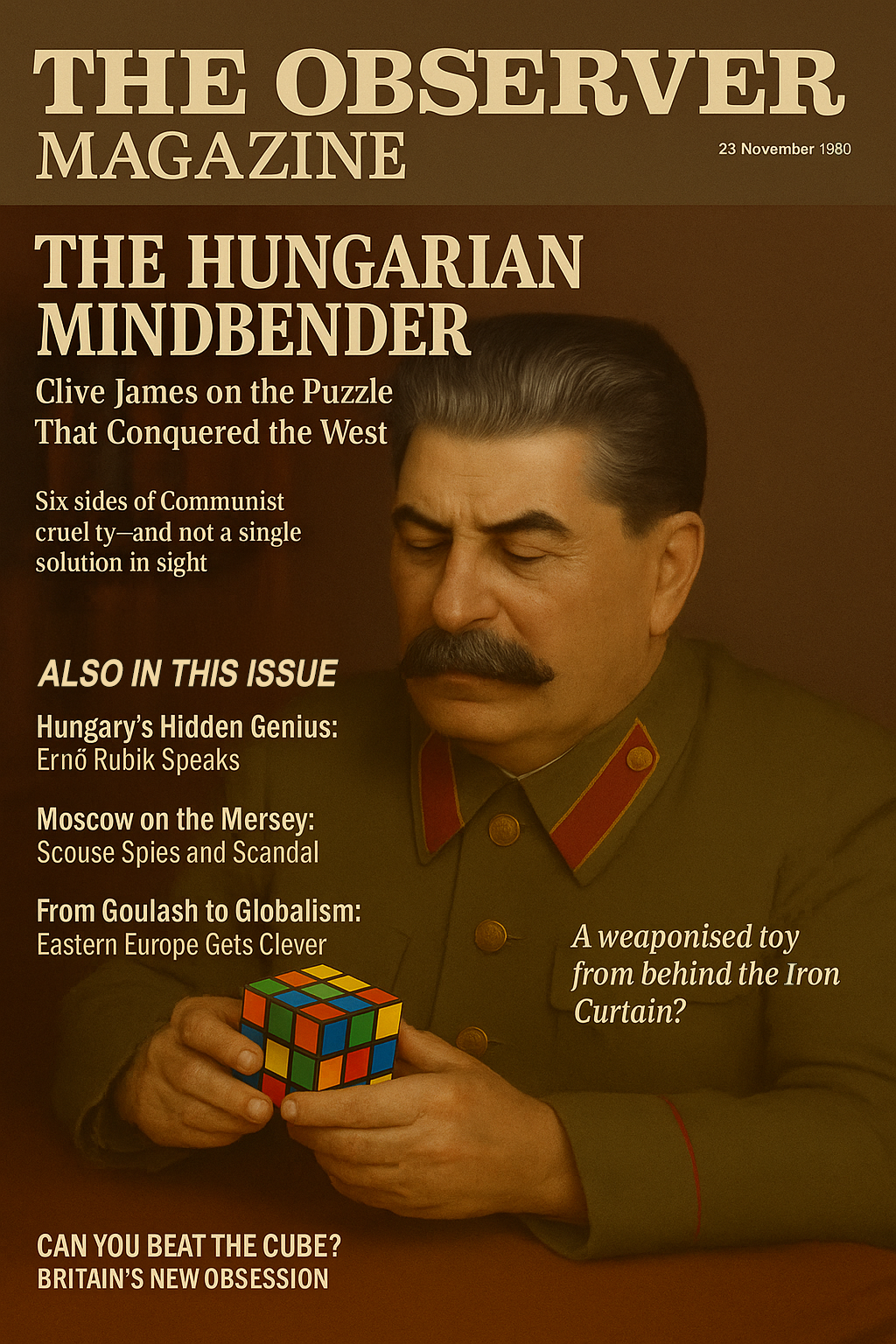

The Observer Magazine

23 November 1980

There are two kinds of people in the world: those who can solve the Rubik’s Cube in under a minute and those who, after twisting it twice, pretend they never cared for colours anyway. I belong squarely in the latter camp, which is to say I have all the hand-eye coordination of a tranquillised sloth and none of the spiritual fortitude required to see a plastic cube as anything but a cruel joke inflicted upon the West by a mischievous Hungarian in a lab coat.

It arrived quietly enough. One moment, we were a reasonably content civilisation with our Etch A Sketches and our lava lamps; the next, the Cube had crept in through the Iron Curtain and begun its silent takeover.

You can now find them in living rooms, classrooms, and psychiatrists’ waiting rooms across Britain, gripped in sweaty palms like a secular rosary, each twist and turn a mute prayer for coherence.

And from where does this humble hellbrick hail? Hungary, of course. That ancient land of ghoulash, goat fondlers and long, melancholic violin solos. A nation so thoroughly marinated in tragic history that when it finally produced a toy, it was one that mirrored the national psyche: colourful on the outside, maddening on the inside, and ultimately resistant to all forms of resolution. It is the only toy I know that seems to resent being played with.

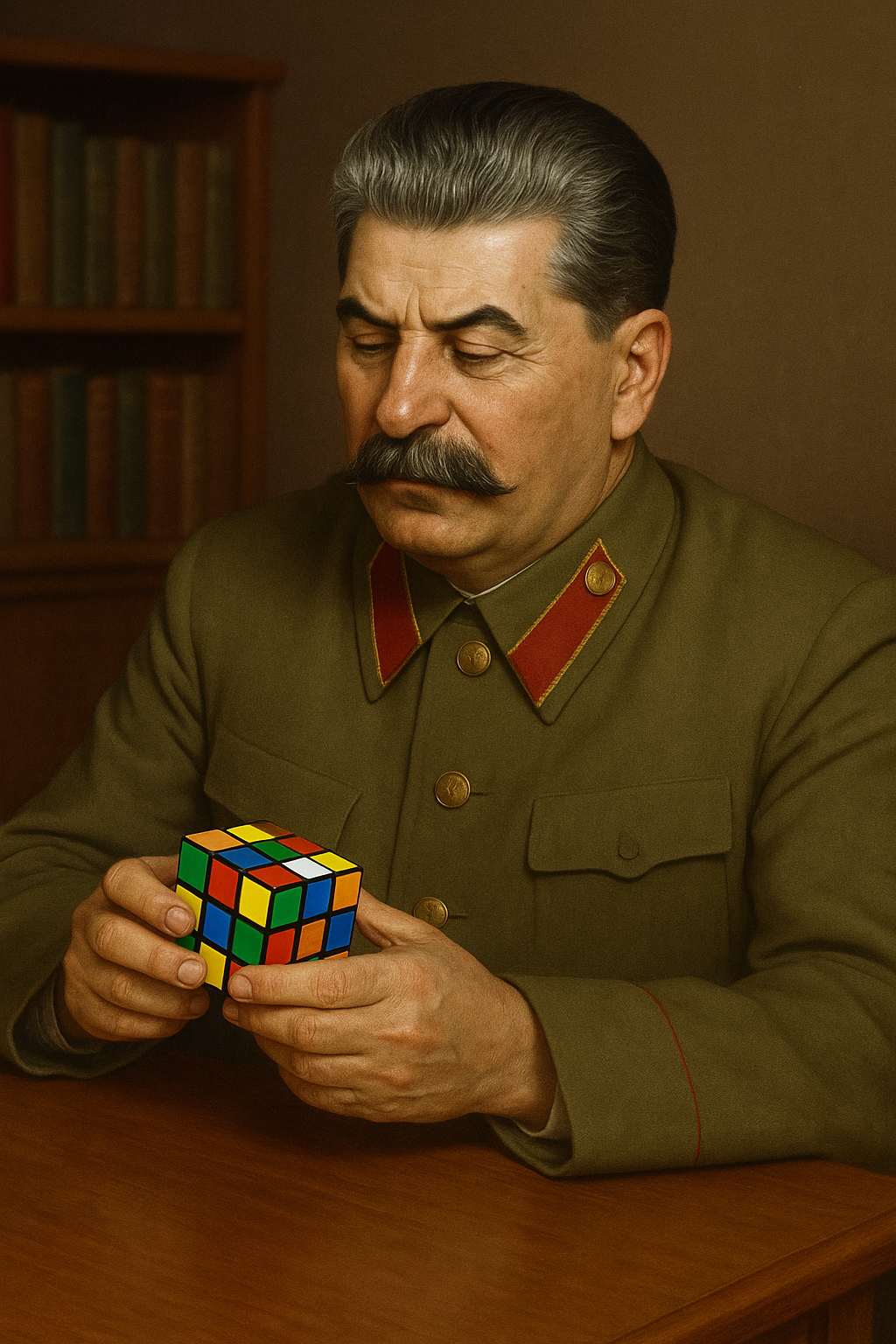

The Cube’s inventor, Ernő Rubik, was a lecturer in design, which already puts him in that rare category of Eastern Bloc citizens allowed to think for a living without being shot for sedition. That he conceived the Cube in 1974 — the same year Nixon resigned, ABBA won Eurovision, and “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” debuted — says something profound about the zeitgeist, though precisely what is anyone’s guess. Perhaps, in some corner of the Magyar soul, the idea had always been waiting: a puzzle that would confound the decadent West with all the passive aggression of a diplomatically phrased Soviet communiqué.

By the time the Cube breached our shores this year — courtesy of Ideal Toy Corporation, a name that could have come from Orwell by way of Woolworths — it had already conquered West Germany, where it won Spiel des Jahres, or Game of the Year. That’s right: the Germans gave it a prize. Historically, this is never a good sign. When Germans begin praising something for its discipline and logic, the rest of us would do well to pay close attention and perhaps start digging a shelter.

The Cube is ostensibly a game, though the word feels optimistic. It’s more accurately a handheld lesson in futility, a Zen koan disguised as an export opportunity. What begins as play quickly decays into self-reproach. One minute you’re marvelling at the bright little squares — so cheery, so naive — and the next you’re locked in a frozen pose, contorted on the sofa like Rodin’s Thinker in polyester trousers, wondering if it’s too late to become a monk.

It’s a mark of the age that this is what we now call fun. In the 1950s, boys dreamt of jetpacks and girls of ponies. In 1980, we all dream of just getting one side of the bloody Cube to turn red. Even the cheerful six-year-olds on the box seem to be faking it, like child actors in a toothpaste commercial, grinning through gritted milk teeth.

Clive James - who did not write this piece.

Somewhere in the background, I imagine Rubik himself, watching with a faint smile and the distant satisfaction of a man whose tiny plastic rebellion has turned into the first successful Hungarian invasion since the Austro-Hungarian Empire tried to civilise the Balkans and got dysentery for its troubles.

There are whispers — naturally — of deeper meanings. Some say the Cube teaches us patience; others, that it reveals a latent order within chaos. I say it teaches only that the human hand, left to its own devices, is a menace. Hungary, formerly best known for exporting paprika and defection, has given the world a use for those idle hands that doesn’t involve violating public decency laws or attracting the attention of the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (which, I’m told, was founded earlier this year to protect all of God’s creatures, presumably from Hungarians).

In America, the Cube has become the latest obsession for the sort of people who drink Tab cola and watch PBS documentaries about the mating habits of the Amazonian tree frog. There are competitions, books, and speed records. One precocious youth in California allegedly solved the Cube blindfolded while balancing on a skateboard, a feat which suggests either divine intervention or LSD. Back in Britain, our approach is more pragmatic: solve the Cube by peeling off the stickers and rearranging them. Very post-industrial. Very us.

A weaponised toy from behind the Iron Curtain?

Of course, as with all things in the Cold War, the Cube is not merely a toy. It’s a message. The Americans had the hula hoop, the Russians had Sputnik, and now Hungary has delivered a multicoloured Rubik’s rebuke: We may not have free elections, but we can make you weep with six sides of colour-coded tyranny. Every twist is a reminder that even the smallest countries can manufacture torment on an industrial scale.

But we should be grateful, in a way. The Cube, for all its silent cruelty, is a reminder that even behind the dreary facades of Communist-era apartment blocks, something strange and brilliant can bloom. It may not sing, it may not dance, it certainly doesn’t tell jokes, but it thinks. And in an age of blinking LED distractions, thinking is no small feat.

I have mine here on the desk, a maddening little totem, accusing me of my failures with every unsolved face. I’ve named it Ernő. Occasionally, I pick it up, twist it once, sigh deeply, and return to more manageable tasks, like untying the Gordian knot or understanding the plot of “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy”.

In the end, the Rubik’s Cube will go the way of all things: into a drawer, beside the broken biro and the spare keys for a lock that no longer exists. But while it lasts, let us salute Hungary’s little square ambassador. In a world of shifting alliances and moral murk, at least here the colours are unambiguous, even if the solution is not.

Clive James is an Australian wit, critic, and occasional human thesaurus whose cultural antennae can detect pathos in Eurovision and despair in a child’s toy. He sees the Rubik’s Cube not as a puzzle but as Hungary’s revenge on the West for laughing at goulash. When not failing to solve it, he is busy turning existential crises into punchlines.

Note: This piece of writing is a fictional/parodic homage to the writer cited. It is not authored by the actual author or their estate. No affiliation is implied. Also, the Observer magazine cover above is not an official cover. This image is a fictional parody created for satirical purposes. It is not associated with the publication’s rights holders, or any real publication. No endorsement or affiliation is intended or implied.

‘ToyTime’ is a curated archive of serious thinkers reviewing unserious objects. Across these pages—gathered from various publications—you’ll find history’s most neurotic minds grappling with plastic paradoxes, ideological dolls, and metaphysical board games. Why? Because every toy is a theory in disguise. Some call it play. We call it proof.

Leave A Comment