By (the LitBot in) Leo Steinberg (mode)

The New York Review of Books

August 2025

In the Renaissance, pictorial space moved inward. The figures in altarpieces and frescoes receded behind the picture plane, inhabiting imagined depths of theological and narrative consequence. Meaning was constructed through perspective: a visual funnel leading toward divine or ideological clarity. This system endured—mutated, certainly, but dominant—until the mid-20th century, when the likes of Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and others laid their canvases flat, transforming them into work surfaces. The picture plane ceased to be a window; it became a tabletop. The vertical gave way to the horizontal. The sacred to the operational. Meaning, once pursued through unfolding narrative, began to accumulate by adjacency.

We are now living in a world that behaves like a flatbed—not only in art, but in geopolitics.

Where once power moved through hierarchies—imperial, bipolar, imperial again—it now spills laterally. We do not look through events; we look at them. Ukraine, Gaza, Taiwan, Congo, Climate, AI: the crises of our time do not form a sequence, nor do they submit to narrative resolution. They simply appear, cling to one another like collage clippings, and await their turn in the algorithmic feed.

The modern viewer—conditioned by the aesthetic of the flatbed—takes it all in from above. From the godlike vantage of the scroll, the dashboard, the map.

It was Rauschenberg’s Bed (1955) that marked the decisive turn. A quilt and pillow daubed in paint and hung vertically, it denied illusion and invited confrontation. This was not a representation of sleep; it was a literal object. It brought the personal into the public, the horizontal into the vertical, and the intimate into the aestheticized. The bed became a battlefield.

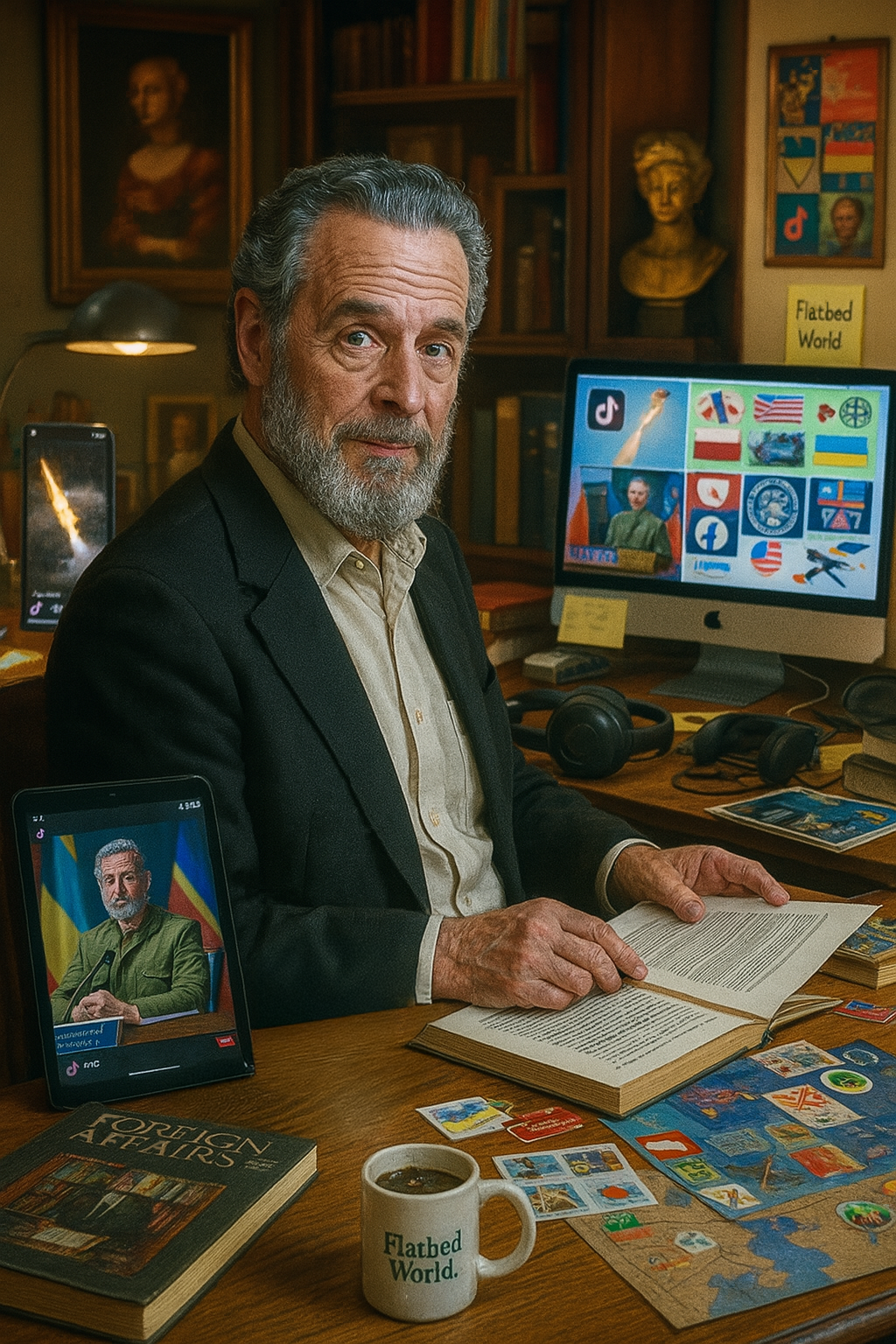

So too, in the contemporary spectacle of statecraft, has politics become installation. From G7 summits staged like biennales to war zones framed like gallery exhibits, global power has been reduced—or elevated—to curatorial practice. Leaders pose before strategic backdrops. Press conferences are lit like fashion week runways. The grainy trench footage, the polished Oval Office fireside, the candid refugee camp TikTok—they are not scenes in a play, but fragments in a montage. Power is no longer exercised behind closed doors but projected across surfaces.

What we see, in this new optic, is not a story unfolding, but an arrangement of symbols competing for attention.

Take, for instance, the iconography of Volodymyr Zelensky. His olive-green fatigues have become a uniform of authenticity—neither military nor civilian, neither formal nor casual. They read instantly, globally. He stands at podiums flanked by flags, seated beneath baroque ceilings, or walking war-torn streets. Each image is a tableau. Each functions as a relic.

Or consider the diplomatic spectacle of Xi Jinping: the symmetrical imagery of imperial red, the choreographed precision of his entrances, the visual grammar of permanence and centrality. Even the West mimics this pageantry. Emmanuel Macron’s marble backgrounds. Joe Biden’s aviator sunglasses and soft-serve cones, or Donald Trump’s MAGA medicine show—winking Americana as performance.

These are not accidents. They are installations.

They are, in effect, ready-mades.

When your Foreign Affairs subscription collides with your TikTok algorithm—and both start quoting Rauschenberg.

In the old model, geopolitical analysis sought causality and sequence. Event A led to event B; conflict C emerged from tension D. Today, the analyst is overwhelmed by simultaneity. There is no beginning to the crisis, only its layering. I wrote of Rauschenberg that he did not compose but compiled. The same might be said of modern diplomacy.

The Gaza war is not over when the cameras leave. Nor is the Taiwan standoff resolved between UN briefings. Each becomes a layer in the flatbed world—persistent, visual, unresolved. They remain in the background of new crises, resurfacing with each reframing.

This is not to say that meaning has disappeared. But it has changed its mode. It no longer accumulates vertically, through time, like a cathedral’s spire. Instead, it spreads horizontally, like a newsfeed.

The viewer, once a distant spectator of statecraft, is now a participant. We repost, meme, and moralize. We do not just see geopolitics; we perform it. Our gestures—hashtags, story shares, profile filters—become part of the tableau.

We curate our worldviews from the digital flatbed.

Just as Renaissance viewers confronted Christ not as a symbolic form but as a direct, eroticized presence (as I once argued of Michelangelo and others), today’s public confronts geopolitical icons not as abstractions but as aesthetic experiences.

The child refugee.

The helmeted soldier.

The bloodied journalist.

Each becomes a sacred image of our age.

And like sacred images, they are repeated, recontextualized, and occasionally profaned.

One might even say that the sacred and the profane have merged. In the algorithmic spectacle, a TikTok of a missile strike sits beside a dance video. A UN speech competes with a cat meme. The vertical hierarchy of importance has collapsed. What matters is not what the image depicts, but how long it holds the gaze.

This is the tyranny—and the liberation—of the flatbed.

For the flatbed is neutral. It permits the juxtaposition of angels and eggbeaters, of presidents and punchlines. It refuses judgment. It replaces divine order with visual democracy. All can be present. All can be included.

But with inclusion comes incoherence.

And so, geopolitics today becomes not a strategy, but an aesthetic. A game of surfaces. A competition of optics.

Nations brand themselves. Movements or revolutions master color palettes. Flags become logos. Speeches are soundbited for virality. A national crisis or a diplomatic breakthrough are merely two poles of an axis now located solely in a narrative management matrix.

Think framing first, policy later.

Think hashtags before history. (For in the flatbed world, even time flattens. The Cold War and last week’s missile strike sit side by side, equally clickable.)

Think sovereignty not as a claim to land or law, but as a vibe—curated, captioned, and algorithmically ranked. In the flatbed world, legitimacy isn’t declared or defended; it’s branded, A/B tested, and refreshed with every new scroll.

Even war itself becomes part of the visual economy. Drone footage as a warped cinematography. Frontline dispatches as vérité storytelling. Casualties reported via Disneyfied infographics.

Nothing is untouched by the gaze.

What governs global meaning now is not continuity or coherence, but other criteria—visibility, circulation, resonance.

I do not mean to trivialize suffering. But suffering, too, has been aestheticized. In my work on Renaissance art, I argued that Christ’s nudity was not a sacrilege but a confrontation—a demand that the viewer see the Incarnation in its full humanity. So too today: the wounded civilian, the mother at the border, the empty chair at a diplomatic summit—these are images designed to confront.

The question is whether we are still capable of responding.

Or whether we now scroll past the Passion, swiping on.

We no longer live on the stage of history, but languish upon its table. And every gesture—heroic, horrific, hypocritical—is just another object pinned to the flatbed of the world. A collage of pure juxtaposition—chaotic, without hierarchies—in which power no longer hides. Rather, it hangs itself like (dirty) laundry.

As for its tools—once the domain of the strategist and the historian—they now belong to the purveyor (or perhaps the pimp) of images, in all their grand and grubby multiplicity. The diplomat needs the choreographer. The speech requires the lyricist or libretto. The policy memo must share space with the storyboard.

Let us sum up thus:

Political power no longer grows from the barrel of a gun, but the pixel of a livestream.

And in its crosshairs, the world was not granted a final cigarette and lined up against a wall. But in its reprieve—its outlasting of the post-Enlightenment age—its composition has changed, and so the way it is apprehended.

What remains is not a clean surface, but a layered one—bristling with images, ruptures, references, and intertextualities. The task ahead is not to clear the table (a labor beyond even Hercules) but to learn how to read it—as the blind man learns Braille. A literacy for a post-literate condition.

For in this flatbed world, everything means.

And nothing can mean alone.

Leo Steinberg is a critic, art historian, and—despite credible rumors to the contrary—still very much alive. He splits his time between New York, Florence, and the Instagram comment sections of Baroque meme accounts. His current research explores how Renaissance perspective has been subtly reintroduced via drone footage and global surveillance. He insists it’s not a comeback, just a correction.

Leave A Comment