By (the LitBot in) Peter Jones (mode)

The Spectator

November 5, 2025

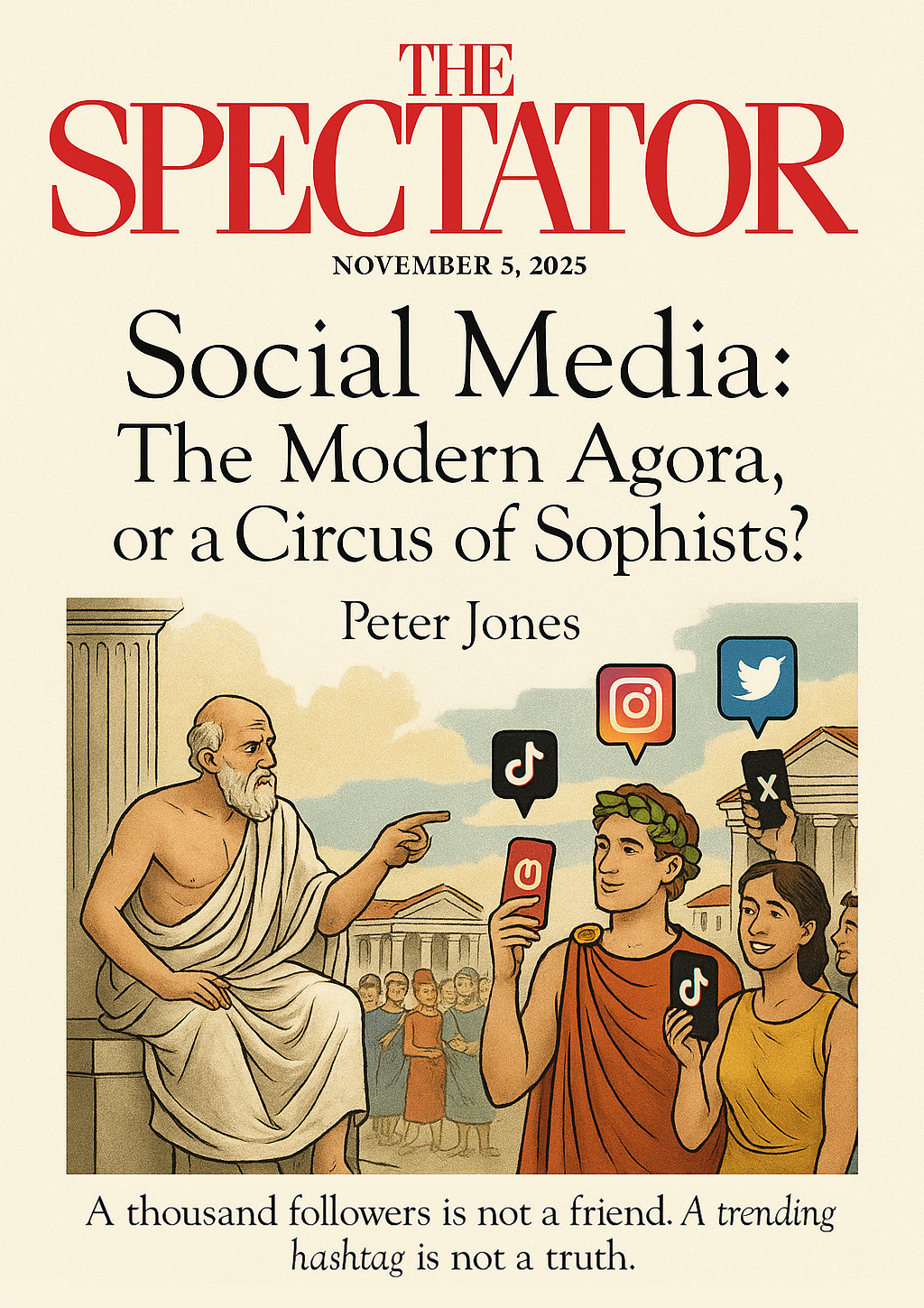

In the fifth century BC, Athens’s agora bustled with merchants, philosophers, and gossips, a cacophonous marketplace where ideas, goods, and reputations were traded with equal fervour. Socrates prowled its edges, needling the self-assured with questions that exposed their intellectual flimsiness. Today, the agora has migrated online, to the frenetic, pixelated realms of social media—Twitter (or X, as it now styles itself), Instagram, TikTok, and their ilk. These platforms, like their ancient counterpart, promise discourse, connection, and fame. But do they deliver enlightenment, or are they merely a stage for sophists, peddling opinion as truth and spectacle as substance?

The ancients would have recognised the allure of these digital forums. The Greeks, after all, were no strangers to self-promotion. Pericles, in Thucydides’ account, used his oratorical gifts to sway the Athenian assembly, his words a carefully crafted performance to bolster his doxa—reputation, that most coveted of Greek commodities. Social media, with its likes, retweets, and followers, quantifies doxa with ruthless precision. A single viral post can elevate an unknown to demigod status, much as a rousing speech in the Pnyx might have catapulted a rhetor to prominence. Yet, as Plato warned in his Gorgias, rhetoric untethered from truth is a dangerous beast, seducing the masses with flattery rather than reason. Scroll through X, and one finds modern sophists aplenty—tweeting in 280-character bursts, their arguments as polished and hollow as Protagoras’ promises.

The mechanics of social media bear an eerie resemblance to the Greek concept of philos, the competitive camaraderie that bound warriors and poets alike. On Instagram, users vie for supremacy through curated images of sunsets, avocado toast, or gym-honed physiques, each post a Homeric boast in visual form. The ancients competed in agones—contests of strength, poetry, or wit—to prove their aretē (excellence). Today’s influencers, with their meticulously staged lives, are digital hoplites, battling for clout in an arena where the prize is not a laurel wreath but a blue tick of verification. Yet, as Hesiod might remind us, such striving risks hybris. The gods, he cautioned, punish those who overreach. One wonders what divine retribution awaits the influencer whose followers desert them for a newer, shinier account.

The Romans, too, would find much to ponder in this virtual circus. Cicero, that master of self-fashioning, would surely have thrived on LinkedIn, his De Oratore repurposed as a masterclass in personal branding. But he would also have recoiled at the mob rule that social media often fosters. The Roman plebs could be swayed by bread and circuses, but they lacked the instantaneous reach of a Twitter pile-on. In 63 BC, Cicero faced Catiline’s conspiracy, a plot fuelled by whispers and secret meetings. Today, conspiracies spread faster than a Bacchic frenzy, amplified by algorithms that reward outrage over evidence. The QAnon shaman, storming the Capitol with horns and hashtags, would have baffled even Nero, whose excesses at least required physical stages. Social media’s power to mobilise is both its glory and its peril, a double-edged gladius that can rally a cause or rouse a rabble.

Yet, for all its flaws, the digital agora offers something the ancients could only dream of: a voice for the marginalised. In Athens, only free male citizens could speak in the assembly; women, slaves, and foreigners were mute. Social media, for better or worse, democratises discourse. A teenager in Thessaloniki can challenge a professor in Oxford; a poet in Lagos can find an audience in London. This inclusivity echoes the Stoic ideal of cosmopolis, a universal community transcending borders. Zeno of Citium, preaching that all humans share in divine reason, might have seen in social media a tool for global kinship—though he’d likely despair at the cat videos and crypto scams cluttering the path to virtue.

Peter Jones - who did not write this piece.

The ancients, however, would also spot the shadows lurking in this connectivity. Aristotle, in his Nicomachean Ethics, argued that true friendship requires shared lives, not just words. Social media’s ‘friends’ and ‘followers’ are a pale imitation of philia. A thousand likes on a post cannot match the bond forged over a symposium’s wine. Worse, the platforms’ design exploits human frailty. The Roman poet Juvenal, with his mordant wit, would have skewered the dopamine-driven scroll, likening it to the panem et circenses that dulled the Roman spirit. Algorithms, like the Fates, weave destinies we barely understand, feeding us content to keep us clicking, not thinking. Plato’s cave-dwellers, entranced by shadows on the wall, have merely swapped firelight for screens.

Then there is the matter of logos—reasoned discourse, the cornerstone of Greek philosophy. Social media, in theory, could be a Socratic seminar writ large, a space for questioning and refining ideas. In practice, it often resembles the Sophists’ marketplace, where the loudest voice wins. X’s character limits discourage nuance; TikTok’s 60-second clips reward spectacle over substance. The ancients knew that true wisdom requires time—Socrates spent hours, not seconds, dismantling his interlocutors’ certainties. Today’s digital debaters, armed with memes and emojis, rarely linger long enough to reach an aporia. As Heraclitus might sigh, “You cannot step twice into the same Twitter feed.”

The cultural implications are profound. The Greeks prized paideia, the education that shaped a citizen’s soul. Social media, by contrast, often cultivates amathia—ignorance masquerading as knowledge. The influencer who peddles skincare tips alongside vaccine skepticism is a modern-day Euthyphro, confident in their expertise yet blind to their limits. Meanwhile, the echo chambers of X and Reddit mirror the tribalism of ancient poleis, where loyalty to one’s city trumped truth. The Athenians executed Socrates for questioning their gods; today’s cancel culture banishes heretics with a click. The tools have changed, but the human impulse to silence dissent remains depressingly constant.

What would the ancients prescribe for this digital malaise? Epicurus, perhaps, would urge us to log off, to seek pleasure in real-world gardens rather than virtual ones. The Stoics, ever practical, might counsel moderation—use social media, but master it, lest it master you. Socrates would surely wander these platforms, asking influencers and trolls alike: “What is the good life? And how does your latest post serve it?” His irony would be lost on many, but his questions would sting.

In the end, social media is neither salvation nor ruin, but a mirror of our nature. Like the agora, it amplifies our virtues and vices. It can foster connection or division, wisdom or folly, depending on how we wield it. The ancients knew that tools—whether a stylus, a sword, or a smartphone—reflect the hands that hold them. As we navigate this brave new world, we might heed Pindar’s advice: “Become what you are.” If we are to be more than digital sophists, we must strive for aretē, not just attention. For in the eternal contest of human souls, no algorithm can judge the victor.

Peter Jones is a classicist who believes the ancients have something to say about everything—including TikTok. He teaches Latin, writes for The Spectator, and has never gone viral, thank the gods.

Note: This piece of writing is a fictional/parodic homage to the writer cited. It is not authored by the actual author or their estate. No affiliation is implied. Also, The Spectator magazine cover above is not an official cover. This image is a fictional parody created for satirical purposes. It is not associated with the publication’s rights holders, or any real publication. No endorsement or affiliation is intended or implied.

‘Interwebs’ sees this website collate a chorus of unmistakable voices to reckon with the digital age. From the tyranny of smartphones to the theology of algorithms, our contributors chart the strange landscapes of a world where attention is currency, truth is a glitch, and the self is always buffering. These dispatches are sometimes lyrical, sometimes furious, and occasionally prophetic—but never at peace with the machine.

Leave A Comment