By Anton Verma

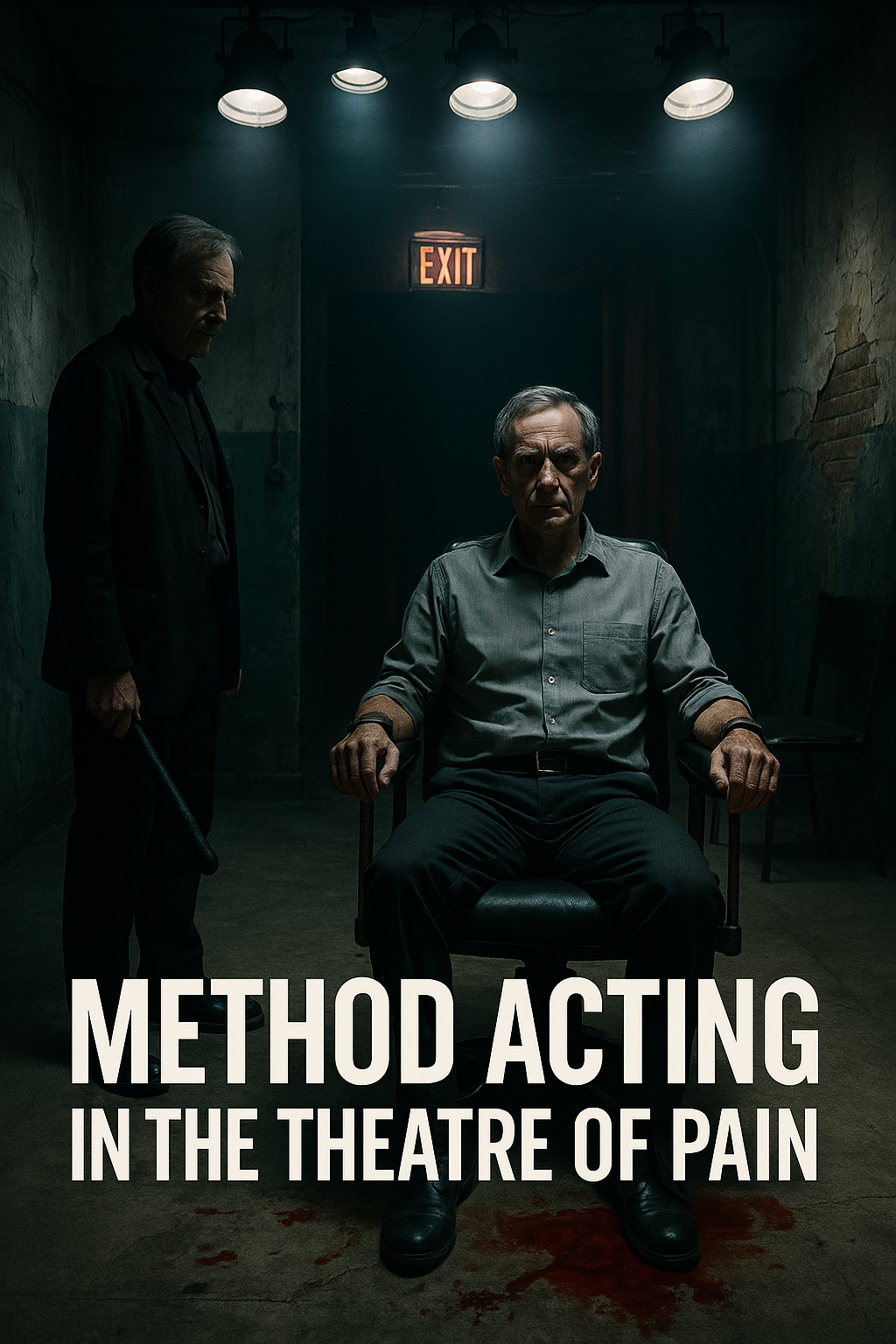

The cell reeked of mildew and stage perfume, a sour marriage of decay and artifice. Faint scratches—prisoners’ last pleas—scarred the concrete walls, barely visible beneath a hasty coat of paint that gleamed under flickering neon lights. A woman in a leather jacket, her wrists bound in clean, padded restraints, stifled a giggle as an actor in a faux-communist uniform barked, “Confess, traitor!” Her laughter echoed, sharp and jarring, against the drip of a pipe somewhere in the darkness. Other patrons, their eyes wide with a mix of fear and thrill, leaned forward on metal benches, their smartphones tucked away per the rules of the third-tier experience. This was the pinnacle of Jan Novák’s vision: The Theatre of Pain, a spectacle of history repackaged for those willing to pay for a taste of terror.

Karel had stood in the shadowed corner, his gaunt frame half-hidden behind a prop table cluttered with rubber batons and fake blood. At seventy-eight, his hands trembled slightly as he adjusted a coiled rope, its pristine fibres a mockery of the coarse hemp he’d once used. His grey eyes, dulled by decades, darted to the patrons—thrill-seekers, Novák called them, with a penchant for the extreme. Some had come for the sadomasochistic rush, others for the historical novelty, but all had paid handsomely to play at suffering in a place where suffering had once been real. Karel’s stomach twisted, a faint nausea he’d learned to ignore. It was a job, nothing more. A way to leave something for his daughter, who hadn’t spoken to him in years.

Decades ago, this cell had been a chamber of the Státní bezpečnost, the StB, Czechoslovakia’s secret police. Karel had worked here, his hands steady then, his voice cold as he’d extracted confessions from men and women deemed enemies of the state. The screams had lingered in his dreams, though he’d told himself it was duty, a necessary cog in the machine of order. After the Velvet Revolution, the machine had crumbled, and Karel had spent three years in a prison not unlike this place, a traitor to a new world that despised his kind. The facility had become a museum for a time, its cells open to tourists who’d gawked at the relics of oppression—rusted shackles, faded interrogation logs. But the museum had faltered, its funding dried up, and the building had sat abandoned until Jan Novák, a Czech entrepreneur with a fortune built on escape rooms all over the continent, had seen profit in its bones.

Novák had bought the facility for a song, one of many such relics across Eastern Europe that he planned to transform. The Theatre of Pain was his flagship, a meticulously crafted immersive experience that promised authenticity. Customised to paying public, first-tier for those merely wanting to dip their toes in the water, all the way up to third-tier, barely this side of actual torture.

The posters, plastered across Prague’s tram stops, had boasted of “reliving history” in “the very cells where dissidents fell.” Karel had seen one such poster on his way to work, the words in bold red: Step into the Theatre of Pain. Feel the Fear. He’d turned away, his reflection ghostly in a shop window, and wondered why the words had stung.

That day, towards the end of the opening week, the technician’s booth, a glass cubicle overlooking the cell, had hummed with the low buzz of a radio. A news report had crackled through, its voice faint but insistent: “Parliament debates a ban on these grotesque spectacles, with critics calling The Theatre of Pain a crass commodification of our nation’s trauma…” The tech, a young man with a shaved head, had snorted and switched it off, muttering about ‘snowflakes’ who didn’t understand business. Karel had paused, his fingers tightening on a rope. The debate had raged for weeks—op-eds in newspapers, protests outside Novák’s office, politicians thundering about decency. Some had argued the experience honoured history, forcing people to confront the past. Others had called it a circus, a desecration of the suffering etched into these walls. Karel had avoided the news, but the words had seeped into his thoughts: commodification, desecration. They had felt like accusations, though he’d pushed them down.

He’d been recruited by Novák himself, a sleek man in his forties with the grin of a creature that could (and would) sell Auschwitz as a weekend retreat. “You’re the real thing, Karel,” he said over espresso in a glassy café. “An StB veteran. People pay for authenticity.” Karel stared into his cup. He’d wanted to refuse. But the thought of his daughter—estranged, unreachable—gnawed at him. The money was considerable, Novák promised. Enough to leave her something in his will. Enough, perhaps, to buy a second chance. Posthumously, at least.

So Karel had signed the contract and stepped back into the cell, now lit by stage lights and scrubbed of its ghosts.

Or so he thought.

The job was mostly mechanical. He handed rubber batons to actors with gym-toned arms, adjusted restraints that mocked the rusted chains he remembered. Each night blurred into the next—the same pseudo-screams, the same safe word protocols, the same grins on the patrons’ faces. They paid dearly to sample curated terror, diluted through performance and safety checks.

The past had become content.

(Though Novák would have said that it had always been content, even when it was still the present—and only someone like him had the vision to monetise the truth.)

The actors asked questions between scenes: “Were the cuffs tighter?” “Did you ever break ribs?” He gave clipped answers, his voice as hollow as the prop nightsticks. Their eagerness made him ill. The cruelty he once executed as duty (for free, of course, in the socialist paradise) now played as entertainment.

One evening, from the technician’s booth above, he overheard Novák brag to investors. “We’ve cornered the market,” he said, triumphant. “The only show with a genuine StB officer. We’re expanding—Berlin, Budapest, Vilnius. Ex-Stasi, KGB, even Securitate. We’ll franchise memory itself.” The laughter that followed chilled Karel more than any scream.

The routine shifted one evening when the technician had called down from the booth. “Got a weird one tomorrow, Karel,” he said, his voice muffled through the glass. “Some guy booked the whole third-tier session. Just him. Paid triple.” Karel had paused, a prop baton in his hand, and felt a prickle of dread. “Who would do such a thing?” he thought aloud. The technician glanced at a clipboard, his brow furrowing, and matter-of-factly read out the patron’s name. “Some bloke called Jan Kovář.”

The name struck Karel like a blow, though he didn’t know why. A face flickered in his mind—scarred, defiant, eyes burning with hate—but it slipped away, a shadow in the fog of memory. He nodded, his fingers tightening on the baton, and resumed his work, but a low-level dread snagged in his gut.

Then coiled tighter.

That night, he lay awake in his cramped Prague apartment, the city’s hum seeping through a cracked window. He remembered a prisoner, a man with a scarred cheek who’d spat defiance even as his voice broke. The memory was vivid—the cell’s chill, the man’s blood on the floor, Karel’s own voice demanding names—but the details were blurred, lost to time. He rose, his joints aching, and pulled the photo of his daughter from a drawer. Her smile, faded on creased paper, offered no answers. He traced her face, his thumb worn against the edges.

The next evening, Karel arrived at the facility, the air heavy with the threat of rain. The cell was quiet, the usual clamour of patrons absent. The technician fiddled with the lights, their hum louder in the silence. Karel prepared the props, his movements slow, his hands unsteady. Then, the door creaked open. A man entered, his frame wiry, his face scarred and weathered. Jan Kovář. He moved with a focused intensity, his eyes locking onto Karel’s with a force that pinned him in place. He walked past Karel and walked up to the technician’s booth. After a short discussion, the technician returned with the patron, and walked over to the actors. A short conversation unfolded before everyone left except Jan Kovář and the technician, who approached Karel. “Look, Mr. Kovář, he’s offered to pay quadruple if it’s a one-on-one session. Just him and you. Mr. Novak gave me discretion to decide out of the ordinary things and I’ve decided to okay it. I know this will be straightforward for you, of course. I mean, given your background and so on. Besides which, you’ve been with us from the start and know how it all goes.”

Karel was somewhat taken aback. What on earth was this patron up to? Was he going to ask for a fourth-tier experience? Actual torture or something like that?

“Right,” the technician said, “I’ll leave you to it.” And with that, he exited the staging area.

Karel was staring after him when he heard Kovář speak: “Shall we begin? I’m paying a lot for this.”

Karel turned around, slightly in a daze, before remembering he had a job to do. He stepped forward, his voice steady as he began the scripted routine: “State your name, traitor.”

But Jan’s response was unexpected, his words precise, their timbre chillingly familiar. “You know my name,” he said, his voice low, cutting through the artifice like one of the razor-sharp implements that used to sit on the tables: the tools of the ‘trade.’

Karel’s heart stuttered, the script slipping from his grasp. Jan sat in the restraint chair, his posture rigid, and demanded, “Tighten it. Like you did before.” The words carried a weight Karel couldn’t place, a memory just out of reach. He complied, his fingers fumbling with the straps, their padding absurdly soft, as he fastened the patron’s left hand. Jan’s gaze never wavered, his eyes burning with something deeper than the patrons’ thrill—anger, perhaps, or something worse. “You were good at this,” Jan said, his voice a hiss. “Show me your Theatre of Pain.”

And it was then that Karel knew who the patron was. For this was no customer, no thrill-seeker, no man seduced by mere curiosity, but a ghost from his past, come to haunt the stage he now lived on.

(Or had he ever been off of it?)

Jan leaned forward, his voice a low rasp that cut through the hum of the lights. “You remember me, don’t you?” He reached into his jacket, his movements deliberate, and pulled out a worn envelope. Photos spilled onto the floor— a woman with a warm smile, two boys with bright eyes, their faces frozen in a time Karel had helped destroy. “Eva,” Jan said, his voice trembling. “My boys, Petr and Tomáš.” He gestured to the cell, his hand shaking. “This place took them from me. You took them. I broke here, Karel. Or should I say ‘sir’ – that’s what we had to call every one of you, remember. Sir, this. Sir, that. Sir, please don’t tear out my fingernails. Sir, please don’t snap my wrist. Sir, please don’t smash my genitals. Well, sir. Your techniques were far more successful than simply busting my flesh. I drank myself so completely under the table after all of that, that my family couldn’t stand me. Surprisingly, they endured it for a very long time. It must have been absolute torture for them. But, finally, sort of like me in this place, they were gone.”

Karel’s breath caught—those photos. He’d seen Jan’s face—his younger face, untouched by decades—in many a nightmare: scarred, defiant, being interrogated in this very cell, half a lifetime ago. The memories flooded back: the prisoner’s blood on the floor, voice cracking under the relentless, oscillating, blows and questions.

Back then, it was the prisoners on their knees on the concrete floor. Now, Karel found himself prostrate. And breaking down, his hands clawing at his face.

“I cannot say anything. I am sorry but what good is that? Just words, I know. I am sorry. Please, forgive me.”

Jan’s eyes glistened, his rage teetering, the brokenness having long since outweighed his anger, long since deluging all in a sea of blank-faced pointlessness. He remained angry, desiring revenge, but against life more than his former tormentor.

Yet life had no face. And so, this creature before him provided the only substitute.

He unfastened his hand then shoved the restraint chair aside, its padded straps absurdly clean, and stepped closer, his voice sharp with demand. “Show me, Karel. Show me your Theatre of Pain. Do it again. Sir, do it again” He gestured to the baton, his scarred face taut, daring Karel to cross the line. “Pick it up. Hit me. I’m paying more than any other bastard has ever paid for this ‘service.’ So hit me, you worthless piece of shit. I’m not talking about those stupid games. ‘Third-tier’ nonsense. I mean for real. Hit me. Smash my nose in so it looks like abattoir pulp. Come on. Like you did then. Let’s go for an encore, we’re on stage after all and your audience of one insists on it. A standing ovation awaits. So rub my nose in it. Smash it to pieces so you can rub what’s left of my nose in it.”

Jan steadied himself, as if his inner demons were about to cause him to keel over. He stood up straight, smiled through the tears, and yelled at the top of his voice: “Ať žije Československá socialistická republika! And I say it again, just so there’s no misunderstanding: Long live the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic!”

He looked back down at Karel, the positions reversed from their last dance in this cell, and said: “Congratulations, sir. It only took you four decades but your techniques succeeded. You finally made me a loyal member of the state. I’d be happy to supply you with the names of all of my accomplices. But, unfortunately, they’re all dead. God rounded them all up and locked them away in escape-proof cells six feet under, so your office will need to contact his.”

Karel stared at the baton, his hands trembling, the screams of the past a distant roar. “I can’t,” he whispered, the words dissolving into the cell’s stillness, his head and heart spinning.

Jan let out a laugh that sounded like a dying man given a five-minute reprieve. “Can’t? Can’t? Why not? I’m right here, paying for the privilege. I’m begging for it. You never had that back then, did you? This is the greatest moment in your life. Don’t you want to celebrate. I want you to celebrate. It’s what we both deserve.”

Karel didn’t move and Jan looked at the scattered remnants of his family decorating the concrete, like his blood and teeth and bone had done last time he had been here.

A proper burial, he decided. Not on the floor of this place like some of the bastard’s victims, who’d chosen to defend their cause to the bitter end.

He knelt, gathering up the photos, his fingers lingering on his wife’s face. He surprised himself when he next spoke, his voice softening, breaking, like a requiem.

“People used to fight for things that were bigger than themselves. Freedom, state, church. The right just to be, as one saw fit. And now?”

He gazed at the neon lights and fake blood.

“A playpen for fools who pay to pretend, before going back to their YouTube videos and takeaway sushi.

“Takeaway lives.”

Karel remembered the one time he had tried sushi and nearly gagged, and wondered where it had all gone wrong. He saw himself in uniform, at the academy. Training, saluting flags and commissars, loud and proud, not a hint of uncertainty. Black and white, red and blue. Bludgeoning traitors into submission, every fist a brick in the wall keeping the foundations firm, the future secure.

Now everything, including the ‘enemy,’ had been reduced to gaudy artefacts and children’s games for generations stuck in an advanced state of arrested development. Props in a playground for a world that had chosen to move on by retreating within itself.

No place for those unable to retreat, who only knew how to move forward.

Or else die slowly.

“I would rather be a prisoner in this place,” he said, “than as I am today.”

A heavy silence fell. Just like before, he thought, when one of the sessions ended, confession delivered, names handed over, or defiance and a pause in activities until the second round.

“You know,” he said, looking around the cell, “this place used to be a museum. After Havel. I never went inside. But once I stood at the perimeter, near the trees. Just stared. Couldn’t bring myself to cross the threshold.”

Karel nodded. “It never stopped being one. They moved the displays, shut the doors—but the real museum goes on. In its living exhibits.”

Jan gave a dry smile. “Curated by regret. The roads not travelled…because one’s legs were broken.”

More silence. Then Karel said, almost to himself, “There used to be a cleaner here. Janitor type. We nicknamed him ‘Dubček.’ He’d mop the blood, wipe down the restraints, air out the screams. Make the place presentable when the bigwigs arrived. The techniques but with a human face.”

Jan tilted his head. “I remember him. He waddled in when they were dragging me out. Like a bureaucratic duck.”

Karel almost chuckled. “Efficient, though. Like clockwork. You could set your watch by the way he scrubbed the floor.”

Jan’s face softened. “I could use a ‘Dubček’ now. To clean up my own cell.”

“Yes, I’d settle for one just to make my life halfway presentable,” Karel said. “Even just to myself.”

And then the silence again, two ghosts fading in and out of what had been and what never was, the flickering neon almost an oscillating sacrament. For the damned.

“You know,” Jan said finally, “I used to think I survived for my family. But I didn’t. I just haunted them until they left. I think I was freer in here, when I was being broken. Everything since has felt like shadow.”

He tucked the photos back into his jacket. The session, like what passed for his life, was over, only this time he would be exiting the room on his feet, on his terms. He wasn’t sure he’d got his money’s worth. Time would tell—If he lived long enough.

As he walked to the door, he stopped, and turned. “The real Theatre of Pain costs nothing and everything and is right out there,” he said.

“And in here,” Karel said, without skipping a beat, gesturing to his heart.

“Of course,” Jan replied.

He turned to go but then paused once more, his voice wry. “You know, if we were madmen—well, more mad than we already are—then we’d make this a regular thing, an annual reunion.”

“Yes,” Karel mused, lips twitching. “It could be an event, the old guard from both sides. There are a handful of my colleagues left.”

“Well then, you could meet up with them, have some beers, and then round up those of your old enemies still kicking. Maybe you could even beat the life out of us again. Speaking for myself, I’d be more than grateful.”

The smile evaporated from Karel’s face. And with that, Jan decided he had had enough.

As the door closed, his old tormentor slowly stood to his feet. The technician and the others would be back any second, to pack things away—young, polished ‘Dubčeks’ of the digital age.

In the corner, though, a red light blinked. Hidden. Watching.

Upstairs, in a sleek office, Jan Novák leaned towards a glowing screen, one hand on the mouse.

He’d watched the scene unfold: two dead men in a cell, tearing each other open like old letters never meant to be read again.

He smiled now, already thinking about viewership, brand extension, and revenue streams—but, most of all, the sheer dark majesty of it all.

It ought to be a religion, he figured. With him as its high priest.

Or god.

He gazed at the Return key with the casualness of a man choosing between a crimson or scarlet tie.

Then he pressed it.

Upload.

© Anton Verma, 2025

Leave A Comment