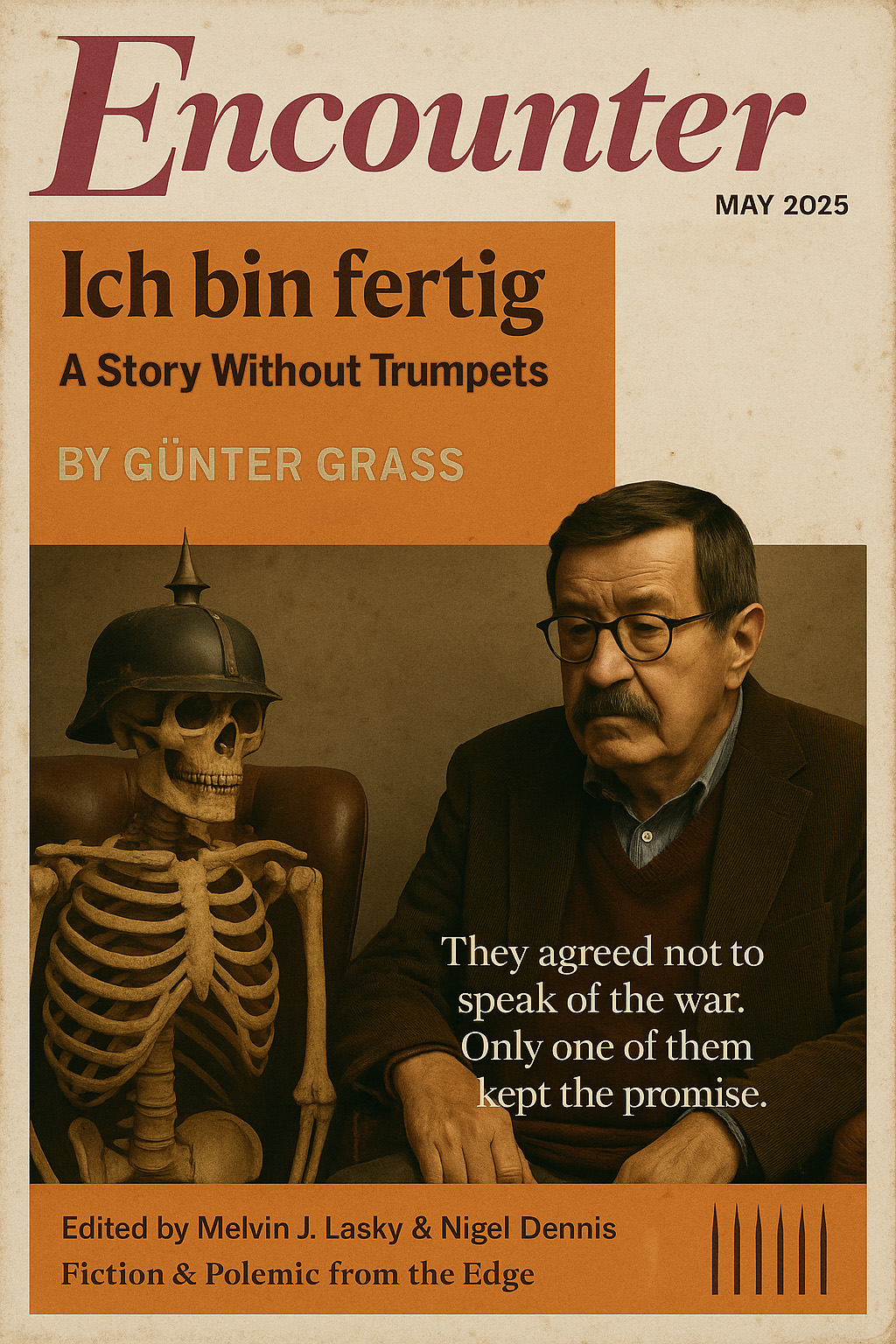

By (the LitBot in) Günter Grass (mode)

Encounter

May 2025

For ‘Stanzas from the Edge,’ Encounter invites poets and other men and women of letters to wax lyrical on a topic of their choice. This edition, (the LitBot in) Günter Grass (mode) meditates on a quiet moment of surrender from the final days of World War II. What begins as an anecdote becomes an elegy for exhausted men, failed myths, and the trench that reappears in every century. Grass speaks not to glorify the past, but to warn us what survives it.

[Translated from the German.]

It is easy to remember the beginning of a war. There are posters and uniforms, loud declarations and cleaner flags. There are parades and choirs and men who walk straighter when the newspapers applaud. The start always makes sense. It has charts and timetables and speeches that sound like history. But it is the end—if it comes at all—that arrives shapeless, toothless, fogged over with fatigue and muttering. The war ends not with trumpets but with men crawling out of ditches and whispering Ich bin fertig. I am done. I just can’t do this anymore.

I was told a story by a man who still carried the war inside him like shrapnel no surgeon had bothered to remove. It wasn’t my war, but it might as well have been. They all blur together. Pick your century. Pick your trench. There are always rats and cold hands and soldiers waiting for something that doesn’t arrive.

His grandfather had been a Feldwebel in the Wehrmacht. Drafted in 1938—before the real horror began, but already too late to be innocent. By 1945 he found himself in a trench behind the Siegfried Line, flanked by ghosts: a Hauptmann who had lost his voice, some barely shaven boys, and three old men who looked like they had been dug up from earlier wars and dressed for this one. The kind of platoon you assemble at the very end, when the Reich is out of youth and out of luck.

The Americans were coming—metal beasts rumbling toward them with flags stitched into their steel. The Hauptmann, mute as a cupboard. The others waited. Looked at the Feldwebel. He was not trained for command. He was trained for orders. But orders had dried up like the food, the fuel, the illusions.

And so he stood. Climbed out of the trench. Not in glory, not in defiance—just upright, back sore, arms limp. He walked toward the American reconnaissance, hands open like a man offering only the truth of his body. No rifle. No gesture. Just this:

Ich bin fertig. Ich kann einfach nicht mehr.

I am done. I just can’t do this anymore.

That was it. No last charge. No flaming rhetoric. Just a man who had reached the limit of what flesh and fiction could carry. He survived. The others, too. Beaten. Exhausted. Alive. As if history had finally granted clemency to those who stopped pretending.

Grass and an old soldier - They'd agreed not to speak of the war. Only one of them kept the promise.

And I think of that trench—call it Siegfried, call it Verdun, call it Bakhmut, call it Gaza, call it the next one—and I see that line echo like a curse across the dirt: Ich bin fertig.

It is not a slogan. It is not even resistance. It is what comes when meaning corrodes and all that remains is the sound of a man trying to save something of himself.

I once believed that language could explain war. That by naming its parts—helmet, bayonet, field stove, rucksack—we could tame it. I made lists. I wrote pages. But now I wonder. Perhaps all we do is decorate the trench with metaphors while the corpses rot beneath our syntax.

The grandfather—he made no such error. He didn’t quote Schiller or Clausewitz. He didn’t wave a white flag. He spoke plain German. He spoke from the marrow. I am done. I just can’t do this anymore.

There is a kind of holiness in that. A surrender not just of the body but of the story.

For stories are what keep wars alive. Not tanks. Not weapons. Narratives. Myths. The kind that tell a man he is part of something sacred. The kind that hang medals on ruins. The kind that convince a boy to crawl through blood for a border that will be redrawn by bureaucrats.

The man who says Ich bin fertig kills the myth. He robs the war of its crescendo. He breaks the rhythm. That is why he is dangerous. That is why we forget him.

No statue. No stamp. No slot in the textbook. Just a whisper in the cold air.

The old man joined his comrades in 2001. His last words were a prayer—of sorts. Not tidy. Not pious. Just raw:

“God, forgive us for what we have done to each other.

I cannot forgive and I cannot forget.”

That is not absolution. That is memory refusing to fade. That is the opposite of forget-me-not flowers and tidy national funerals.

That is a soul standing in its own crater.

I wonder what he would say now—if he saw the old wars flaring again under new headlines, new justifications, the same smoke.

I imagine him at a table, a worn coat on his shoulders, fingers tracing the rim of a chipped cup. He watches the news. The flags look different. The faces too. But the trench is still there. And the men in it are still waiting for someone to say the thing they all feel in their bones:

Ich bin fertig. Ich kann einfach nicht mehr.

Günter Grass is a novelist, sculptor, draft-dodger, artilleryman, moralist, and professional embarrassment to every German politician who ever asked for forgetfulness. He believes in memory as a wound that must be kept open. He adopted a low profile in 2015, but occasionally writes from the shadows of recent wars. This is one of those occasions.

Note: This piece of writing is a fictional/parodic homage to the writer cited. It is not authored by the actual author or their estate. No affiliation is implied. Also, the Encounter magazine cover above is not an official cover. This image is a fictional parody created for satirical purposes. It is not associated with the publication’s rights holders, or any real publication. No endorsement or affiliation is intended or implied.

Leave A Comment