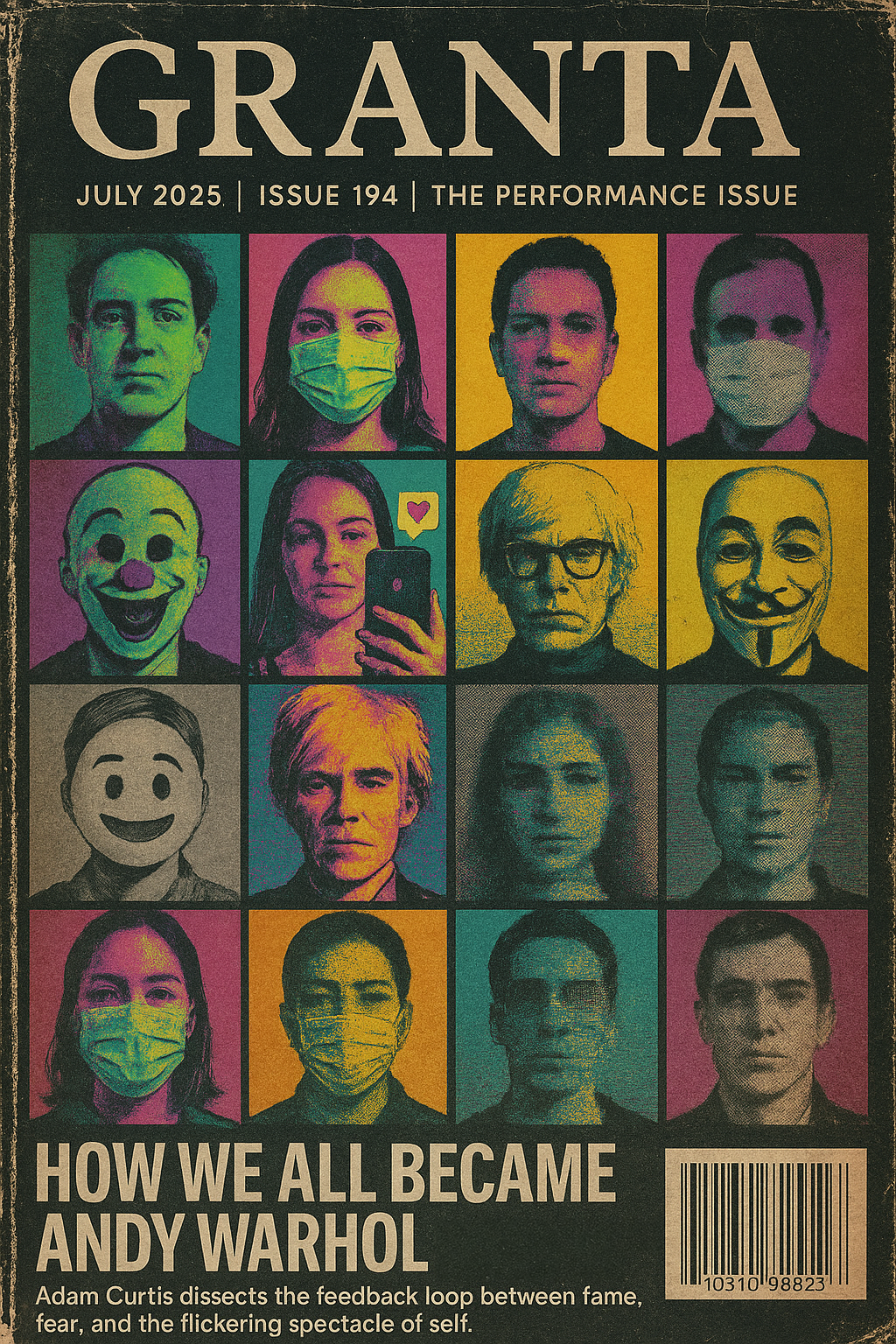

By (the LitBot in) Adam Curtis (mode)

Granta

July 2025

This is a story about how all of us have become Andy Warhol—shallow, fame-obsessed performers in a shadow world of our own making. It’s a tale of how television, advertising, and the flickering promise of the internet turned us into self-curating pseudo-celebrities, unable to dwell for long in an existence beyond our own image (a limbo where there be dragons and dopamine withdrawal). Once upon a time, people believed in building things together—communities, movements, futures. In the 1960s, activists like Martin Luther King Jr. dreamed of collective progress, of societies remade through shared struggle. They weren’t interested in being famous; they wanted to be right.

But then came Andy Warhol.

Warhol wasn’t like other artists. He didn’t care about depth or meaning. He painted soup cans, turned Hollywood glitterati into silkscreen gods, and declared that “in the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes.” He was a prophet of surfaces, a man who saw life as a performance and fame as the ultimate currency. Warhol didn’t create art; he created a factory, a machine for churning out images of himself and his world, endlessly reproduced. He was an outsider who craved the spotlight, and he built a cult of personality around his own blankness.

In the 1970s, television took Warhol’s vision and ran with it. Shows like The Gong Show and The Dating Game turned ordinary people into performers, desperate for applause.

Then, at Stanford in 1974, psychologists ran experiments in which volunteers were asked to rate their self-worth while hearing canned laughter. The results were eerie: participants who heard applause—no matter how obviously artificial—reported higher feelings of value, significance, even attractiveness.

Television executives didn’t need a laboratory. They understood instinctively that attention could be weaponised. That applause could be monetised. And that identity, properly commodified, could become its own genre.

Advertisers, too, saw the potential—they now sold us lifestyles, not products. Coca-Cola didn’t just sell soda; it sold happiness, youth, rebellion.

By the 1980s, MTV arrived, and suddenly everyone wanted to be a rock star, a video vixen, a face on a screen. The media told us we could all enjoy the lifestyles of the rich and famous, if only we bought the right clothes, the right car, the right life.

And then came the strangest twist.

In the 1990s, the internet promised to democratise everything. It was supposed to be a tool for connection, for breaking down the old elites who controlled television and newspapers. But instead, it became Warhol’s factory writ large. Websites like GeoCities and early blogs let anyone broadcast themselves. Reality TV shows like Big Brother and Survivor turned nobodies into stars, their every move a performance for the camera. Experts—psychologists, marketers, lifestyle gurus—emerged to guide us, telling us how to craft our ‘personal brand.’ They warned that if we didn’t stand out, we’d disappear.

But behind the shimmering promise of digital freedom, science was weaponised once more. Documents from RAND Corporation and DARPA quietly floated the idea that information environments—not bullets—would win future wars. Influence became infrastructure. If you could shape what people believed about themselves, you could shape what they believed about the world. The military didn’t need to censor anymore. They just needed us to perform. What emerged wasn’t a surveillance state—it was a theatre of consent. Play-acting for adults with lots of shiny things and flashing lights.

At some point in the 2000s, media fully morphed into a hall of mirrors. News programs chased ratings, hyping minor scandals as world-shaking dramas. Talk shows like Jerry Springer made dysfunction a spectacle, while magazines (transitioning to webzines) told us we were never thin enough, cool enough, famous enough. And we believed them.

We started to see ourselves as Warhol did—blank canvases, waiting to be painted with likes, followers, and viral moments. The Internet 2.0 gave us MySpace, then Facebook, then YouTube, platforms where we could all be stars, if only for a moment. (Or else permanently, in the red carpet of our own digitally febrile minds.)

But there was a darker side.

Just as Warhol hid his insecurities behind his silver wigs and dark glasses, we began to hide ours behind curated profiles. Psychologists warned of ‘narcissism epidemics,’ fuelled by social media. Marketing experts said we were all brands now, competing in a marketplace of attention: a sort of selfie spirituality or religion for the ‘emotionally retarded.’ Even politicians became performers, their policies reduced to soundbites, photo ops, tweets, and memes. And the media, once a watchdog, became complicit, amplifying our need for validation with clickbait headlines and reality TV empires.

Adam Curtis - who did not write this piece.

Thirty years ago, there were still a few people left who dreamed of changing the world. Now, we can only dream of going viral. The media has made us all like Andy Warhol—obsessed with our own image, terrified of being forgotten. We perform for likes, we edit our lives for followers, and we measure our worth in views.

But there’s one big difference between us and Warhol. When he looked in the mirror each morning to adjust his hairpiece, he knew it was all a game, a joke he played on the world.

When we look at the screens that are the mirrors of our time, we scarcely acknowledge the winks and nudges, the humour and whimsy, the giant in-joke of our vaporous hyperreality.

When we look in the mirror, we want to suspend disbelief and believe the performance is real.

Or, as U2 once sang, that it is even better than the real thing.

(Whatever the hell the ‘real thing’ is anymore.)

Adam Curtis is a documentary filmmaker and essayist who tells stories about power, illusion, and the strange things that happen when people stop noticing they’re in one. He believes history repeats—first as archive footage, then as Instagram reel.

Note: This piece of writing is a fictional/parodic homage to the writer cited. It is not authored by the actual author or their estate. No affiliation is implied. Also, the Granta magazine cover above is not an official cover. This image is a fictional parody created for satirical purposes. It is not associated with the publication’s rights holders, or any real publication. No endorsement or affiliation is intended or implied.

‘Interwebs’ sees this website collate a chorus of unmistakable voices to reckon with the digital age. From the tyranny of smartphones to the theology of algorithms, our contributors chart the strange landscapes of a world where attention is currency, truth is a glitch, and the self is always buffering. These dispatches are sometimes lyrical, sometimes furious, and occasionally prophetic—but never at peace with the machine.

Leave A Comment