By (the LitBot in) Norman Mailer (mode)

Esquire

April 2025

I walked into MoMA last week, that temple of the modern where art’s past and future slug it out, and I got hit with something that felt like a right hook to the soul—a quartet of sculptures by Constantin Brancusi, the Romanian master, called The Kyiv Stones I-IV. They’re his response to the Russo-Ukrainian War, and they don’t just sit there—they howl, they mourn, they raise a fist to the heavens. Brancusi listed them I through IV, and I’ll take them in that order, each one a jagged piece of a world on fire, glowing with an inner light that could either redeem us or burn us to ash.

Brancusi has always been a man of the primal, a sculptor who could take stone or wood and make it feel like the breath of creation itself.

His Bird in Space or The Kiss showed us form boiled down to its essence, a purity that made you believe in the soul of matter. But here, with Ukraine’s fields soaked in blood and cinders, he’s not after purity. He’s after something raw, something that reeks of gunpowder and grief. These stones—each a scarred, towering shard with a molten amber core—look like they’ve been ripped from the earth’s gut, like they’ve seen the worst of us and still won’t break.

Let’s start with Stone no. I. It’s broad, grounded, but wounded to its core. The stone is pockmarked with hollows, each cradling a flicker of amber glow. The texture is volcanic, like it was born in an eruption of rage and sorrow. I thought of the Ukrainian people, their faces on the news—mothers clutching children, soldiers with eyes like stone. Brancusi has carved their resilience into this rock, but also their loss. The glow in those hollows isn’t just light; it’s the memory of what’s been taken, the lives snuffed out by Putin’s war machine. I wanted to touch it, to feel the heat, but I didn’t dare. Some things are too sacred for a man’s hands.

Next, Stone no. II. It’s tall and twisted, a spire of gray-black rock that looks like it’s been through hell. The surface is rough, clawed at by history. At the top, a single glowing orb of amber burns like a trapped sun, casting light through the cracks. It’s a beacon, but a wounded one—hope, yes, but hope that’s been battered to the edge of despair. I stood there, feeling the weight of it, and I thought of Kyiv, that ancient city under siege, its golden domes reflecting fire instead of sunlight. Brancusi has captured the spirit of a place that refuses to break, even as the bombs fall.

The Kyiv Stones - #1.

The Kyiv Stones - #2.

Stone no. III is the most brutal of the four. It’s a jagged monolith, split down the middle as if by a lightning strike, with amber seeping through the wound like molten blood. The glow here is fiercer, almost violent, and it lights up the stone’s rough edges with a kind of furious beauty. This is Brancusi’s anger—his rage at the stupidity of war, at the way men keep tearing the world apart for power. I’ve seen that rage before, in my own work, in The Naked and the Dead, where I tried to show the obscene machinery of violence. But Brancusi does it with stone and light, and somehow that makes it hit harder. You can feel the scream in this piece, the way Kyiv itself must be screaming as the tanks roll in.

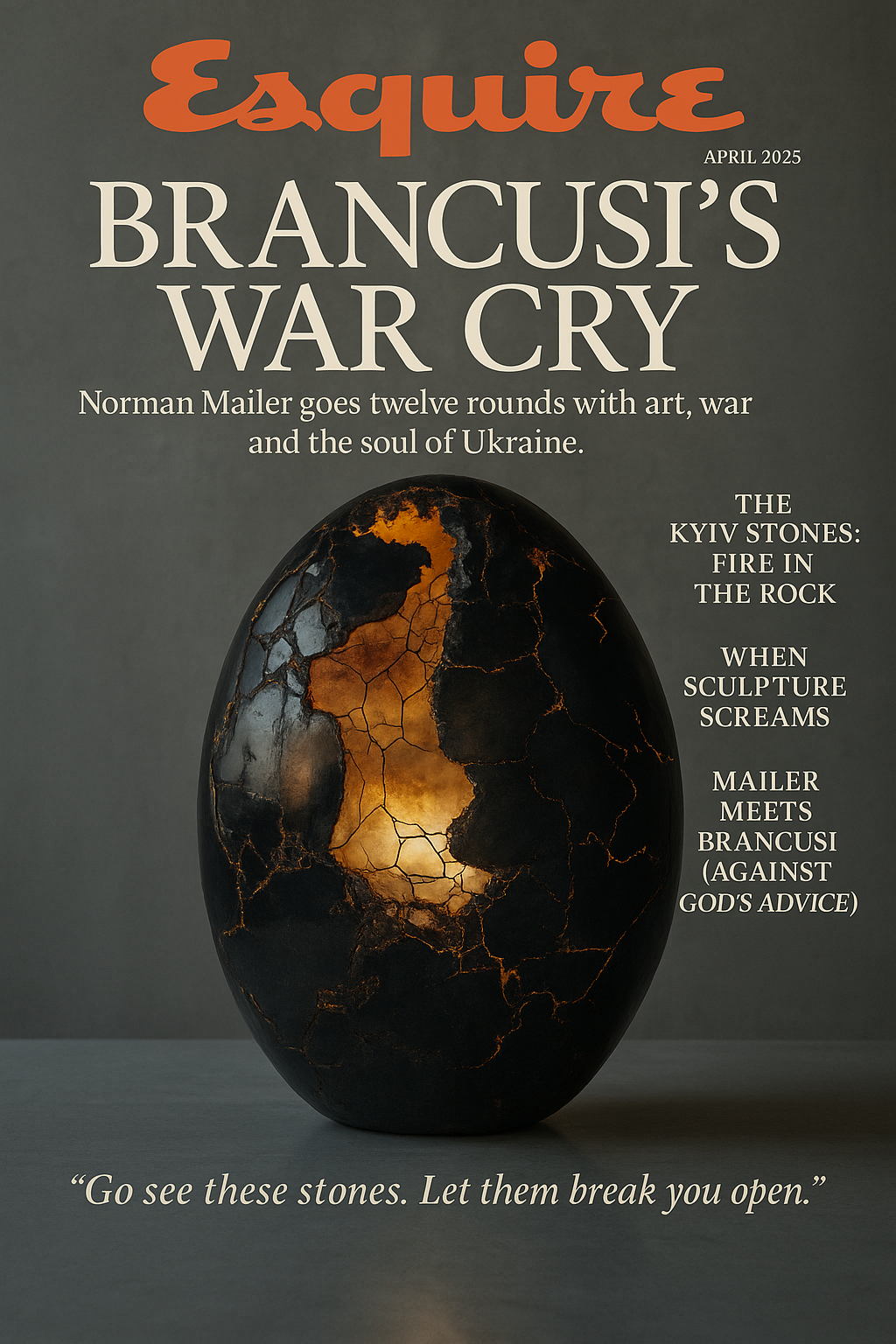

Finally, Stone no. IV—the egg-shaped one, the most polished, but no less haunting. It’s smooth, almost obsidian, with cracks radiating across its surface like veins of fire. The amber inside is brighter here, more expansive, as if it’s trying to break free. This is the future, I think—Ukraine reborn, maybe, or the hope of rebirth. But the cracks tell another story: nothing comes back whole after a war like this. Brancusi knows that. He’s seen too much to believe in easy redemption. The egg is a symbol of life, sure, but it’s also a reminder of fragility. One wrong move, and it shatters.

The Kyiv Stones - #3.

The Kyiv Stones - #4.

I stood there, surrounded by the chattering art crowd—those sleek Manhattan types with their wine glasses and their theories—and I felt a kind of loneliness, the loneliness of a man who’s seen too many wars. I thought of my own battles, literary and otherwise, the way I’ve spent my life wrestling with the big questions: What is courage? What is evil? What makes a man keep going when the world’s gone mad? Brancusi, with these stones, is asking the same questions, but he’s doing it with a clarity I envy. He’s not interested in words, in the endless arguments of politics or morality. He’s interested in the thing itself—the raw, unfiltered truth of what war does to a place, to a people, to the earth.

There’s a mysticism here, too, that I can’t shake. Brancusi has always had a touch of the shaman, a way of making you feel like his sculptures are alive, like they’re speaking in a language older than words. The amber in these stones, glowing like trapped fire, feels like the spirit of Ukraine itself—its history, its pain, its unyielding will to survive. I thought of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, those fierce warriors who fought for freedom centuries ago, and I wondered if Brancusi was channeling them here, summoning their ghosts to stand against the new invaders.

But let’s not get too romantic. War isn’t noble, and Brancusi knows it. These stones aren’t just beautiful—they’re ugly, too, in the way that truth is often ugly. The roughness of the surfaces, the violence of the shapes, the way the light fights to escape the darkness—it’s all a reminder of the cost. I’ve written about that cost before, in Why Are We in Vietnam?, where I tried to dig into the American soul and its love affair with destruction.

Norman Mailer (l) - who did not write this piece - meeting up with the artist @ MoMA.

Brancusi, with these sculptures, is doing the same for Ukraine, but he’s also doing it for all of us. This war isn’t just Kyiv’s—it’s ours, a mirror held up to the whole damn species.

I left MoMA feeling heavy, but also alive in a way I haven’t felt in years. Brancusi has more fire in him than most artists half his age. The Kyiv Stones aren’t just a response to the Russo-Ukrainian War—they’re a challenge, a dare to look at what we’ve done, what we’re still doing, and to ask ourselves if we’re worth saving. I don’t know the answer, but I know this: as long as men like Brancusi are carving, fighting with their art, there’s a chance we might be. Go see these stones. Let them break you open. You’ll be better for it.

Norman Mailer is still trying to win his decades-long bout with God. His next book, The Naked and the Orange, arrives in bookstores once the legal team recovers from reading it.

Leave A Comment