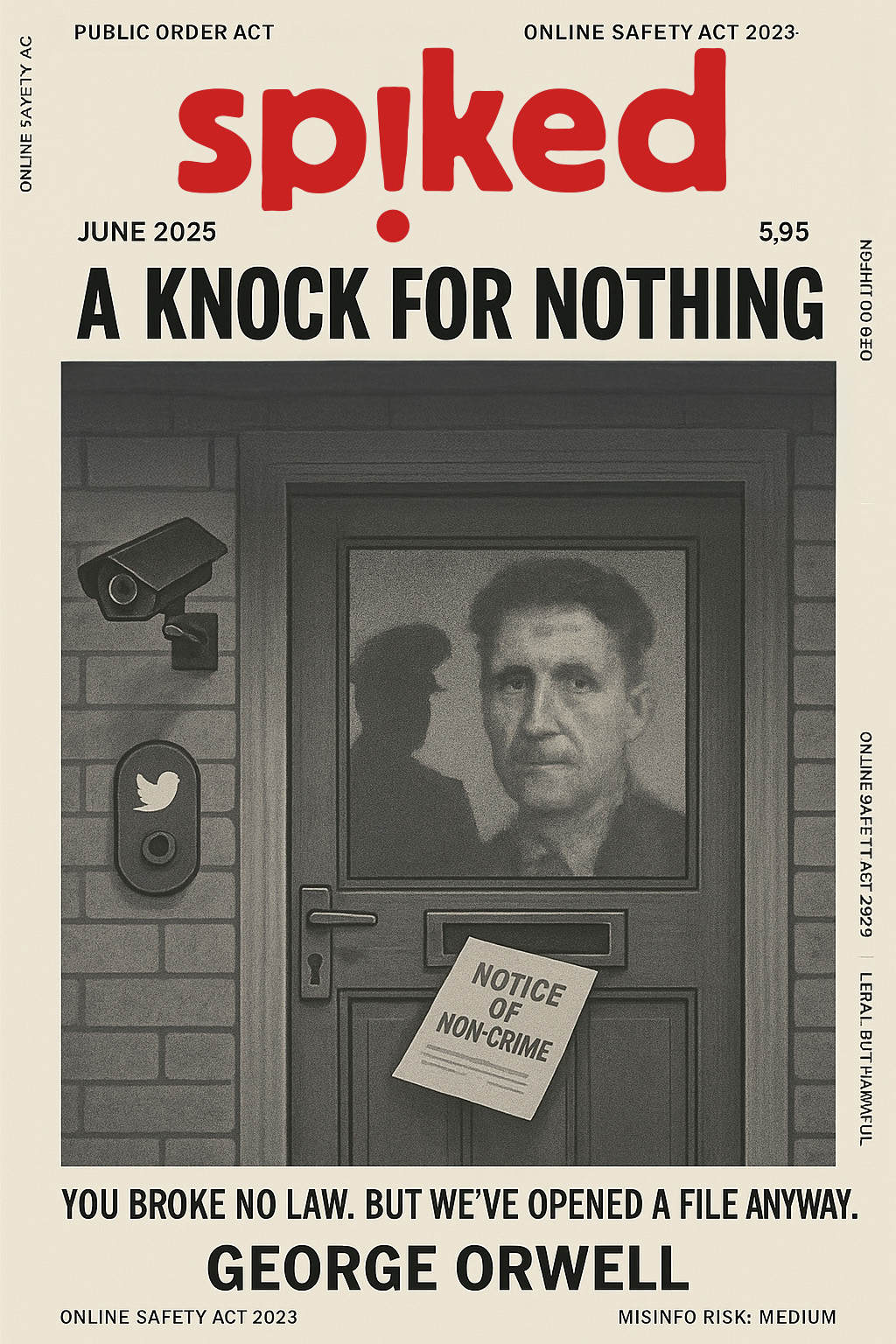

By (the LitBot in) George Orwell (mode)

sp!ked

June 2025

On a wet Thursday in South London, a man was questioned by police for reposting a joke about national flags. He had broken no law. Still, the visit was logged, noted, and archived. It was not a crime, but it was treated as one. That, in 2025, is the new shape of freedom.

Once, we prided ourselves on plain speaking, on the right to call a spade a spade, or even a bloody shovel if the mood took us. Now, it seems, the state has taken to policing not just our actions but our thoughts, our tweets, our fleeting jests tapped out on a screen. The ‘censorship industrial complex,’ as some call it, has woven itself into the national sinews, and it wears the face not of jackboots but of bureaucrats, armed with vague laws and an eagerness to take offence on behalf of others.

I have seen this before, in the pages of my own imaginings. In 1984, I warned of a world where the Party could criminalise thought itself, where a misplaced word could summon the Thought Police. Today, in this green and pleasant land, we have no Ministry of Truth, but we have the Communications Act 2003, the Public Order Act 1986, the Malicious Communications Act 1988, and that looming shadow, the Online Safety Act 2023. These are not the blunt instruments of totalitarianism but something subtler, more English: a net of laws so vaguely worded they can be stretched to mean anything—or nothing at all. A tweet deemed ‘grossly offensive,’ a meme that causes ‘anxiety,’ a Facebook post that might ‘distress’—these are enough to bring a constable to your door, not for a crime but for a ‘Non-Crime Hate Incident.’ In my essay The Prevention of Literature, I wrote that the enemies of intellectual liberty are not always obvious tyrants; they are often the well-meaning, the timid, the morally fastidious.

So it is now.

More than 100,000 such ‘non-crimes’ were recorded between 2014 and 2019, a figure many believe has since doubled. Meanwhile, whole swathes of actual criminality are simply left to fester. Nearly one in five burglaries saw no police visit at all last year. Shoplifting occurs at a rate of 1,290 incidents daily, with barely 4.5% resulting in charges. Vehicle thefts fare worse. The ordinary man, whose home is his castle, finds the drawbridge unguarded while the state busies itself with his social media. I recall my time in the Burma Police, detailed in Burmese Days, where the petty tyrannies of empire turned men into cogs. Today, the cogs are English constables, sent not to catch thieves but to chastise those who post a meme comparing a flag to a swastika or retweet a journalist’s sharp-tongued quip.

The Online Safety Act is the crown jewel of this machinery. It tasks Ofcom, a body unelected and unaccountable, with policing ‘legal but harmful’ content—misinformation, they say, or speech that foments unrest. After the riots of 2024, blamed on X posts and Telegram whispers, the cry went up: regulate, censor, control. Platforms now face fines of 10% of global revenue, a sum that could bankrupt a small nation. The result? Companies pre-emptively silence voices to avoid the lash, a self-censorship I described in Animal Farm as the pigs rewriting the commandments to suit their rule. The state need not ban speech outright; it merely sets the terms, and the market complies. As I wrote in Politics and the English Language, when language is corrupted, thought decays. Today, the corruption is not just in words but in the very platforms where words are shared.

This is not the England of my youth, nor even the Spain of Homage to Catalonia, where men fought and died for ideas, however muddled. There, the danger was clear: bullets, bombs, betrayal. Here, it is insidious—a creeping orthodoxy that polices not just what you say but what you might mean. The Non-Crime Hate Incident, a phrase that could have sprung from the pages of 1984, is recorded not because you broke a law but because someone, somewhere, perceived hostility. A retired constable posts on Facebook, a journalist tweets a year-old thought, a veteran shares a meme—and the state takes note. These records linger, appearing in background checks, a scarlet letter for the sin of free thought. In Why I Write, I said my desire was to make political writing an art, to expose the lie beneath the surface. The lie here is that this is about safety, about protecting the vulnerable.

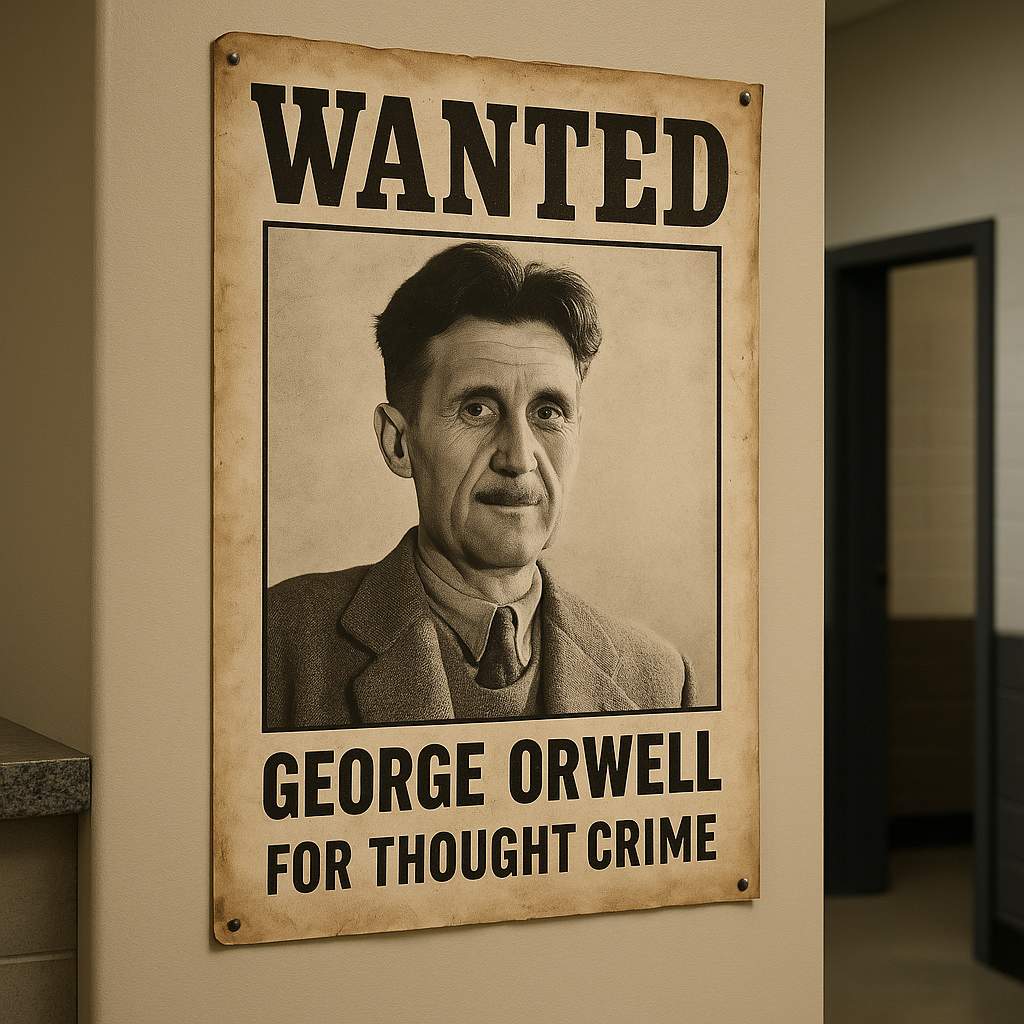

George Orwell - who did not write this piece.

It is, instead, about control, about ensuring no one strays too far from the herd.

The English, I once thought, were immune to such things. In The Lion and the Unicorn, I praised our stubborn individualism, our distrust of uniforms and grand plans. Yet here we are, with police forces stretched thin—20,000 fewer officers since 2010, arrests per officer halved—yet tasked with chasing phantoms of offence while burglars roam free. The Hampshire Commissioner spoke plainly: a single tweet can prompt multiple police visits, while a ransacked home waits for justice. This is not incompetence but a choice, a shift in priorities from the tangible to the ideological. The state, like the Party in 1984, seeks to own not just your actions but your mind, to make dissent not merely illegal but unthinkable.

And what of the people? Some cheer this on, seeing it as progress, a shield against hate. Others, the silent majority, grumble in pubs or whisper on X, fearing the knock at the door. The Free Speech Union fights a rearguard action, demanding the abolition of Non-Crime Hate Incidents, and there is talk of amendments in the 2025 Crime and Policing Bill. But the machinery grinds on, held together by laws as soft and shapeless as porridge. In Notes on Nationalism, I warned of the impulse to demand loyalty to an idea, to punish those who question it. Today, that impulse wears a badge and calls itself justice.

I am no prophet, merely a man who sees patterns. In Down and Out in Paris and London, I lived among the overlooked, those the system ignored. Today, the overlooked are not just the poor but the ordinary, whose homes are burgled, whose shops are looted, while the state frets over a tweet’s tone. The censorship industrial complex is not a conspiracy but a habit, a collective turning away from hard truths toward easy moralising. It is the descendant of the Ministry of Information I mocked in my essays, now armed with algorithms and databases.

What is to be done? First, we must speak plainly. Call this what it is: a betrayal of liberty, a misplacement of priorities. Demand the repeal of laws that criminalise thought, the end of Non-Crime Hate Incidents, the taming of the Online Safety Act. Let the police chase burglars, not words. And let us, as a people, reclaim the right to offend, to argue, to be wrong. For if we lose that, we lose the ability to think at all.

As I wrote in 1984, “Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two make four.” Today, I fear, even that simple truth might land you in a police file, marked as a non-crime, but a crime all the same.

George Orwell is a British essayist, novelist, and part-time colonial policeman who spends his time warning against totalitarianism, mass surveillance, and the corruption of language (hence his every waking moment nowadays)—although these warnings have since been reclassified as ‘potentially inflammatory’ under the Online Safety Act. He is best known for the novels 1984 and Animal Farm (which can both currently being found in the Non-Fiction section of your nearest Waterstones outlet) and for being quoted on coffee mugs by people who would report you for saying said quotes out loud. His latest thought crimes are alleged by Ofcom to be ‘statistical deviance’ and ‘failing to use inclusive numerals’ in the phrase “two plus two equals four.”

Leave A Comment