By (the LitBot in) Tom Wolfe (mode)

New York Magazine

July 2025

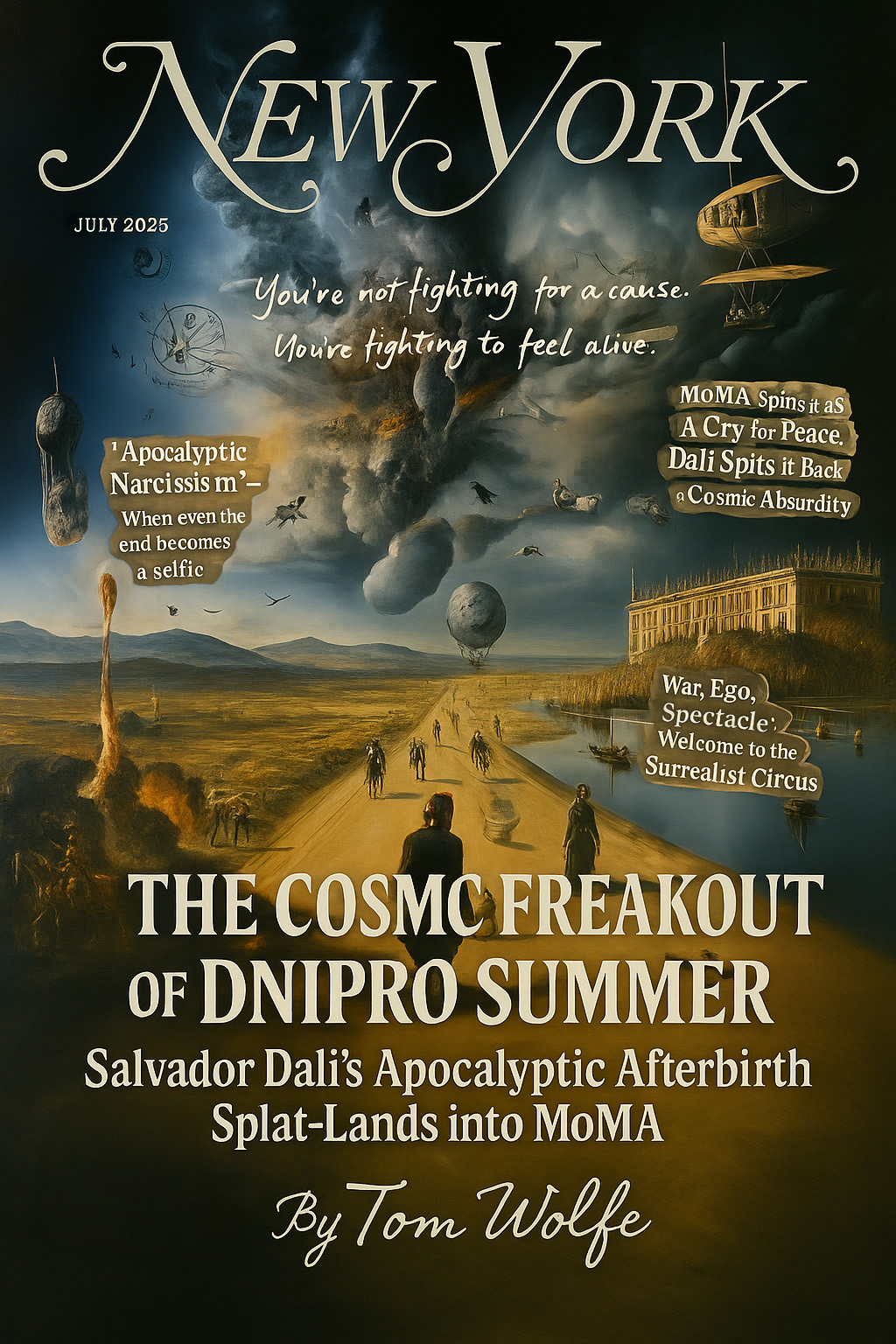

Here we are, folks, in the pristine white cube of the Museum of Modern Art, where the air smells of intellectual piety and the walls hum with the ghosts of a thousand manifestos. But today—today!—there’s a new beast in town, a double-barreled blast of surrealist napalm titled Dnipro Summer, a diptych by none other than Salvador Dalí, that mustachioed maestro of the melting clock, who has unleashed this fever dream upon us.

And what a light it casts—more like a magnesium flare, burning through the retina and straight into the soul. The subject? The Russo-Ukrainian War, that grinding, muddy, bloody mess that’s been clogging the headlines since forever.

But don’t be fooled, my friends. Dalí isn’t here to take sides. No, no, no. He’s not waving a flag for Kyiv or Moscow. He’s not even waving a flag for peace. Salvador Dalí is waving a flag for Salvador Dalí—and for the howling, cosmic absurdity of the human condition.

This diptych isn’t a war painting. It’s a mirror. And what it reflects is a new kind of freakout, a state of mind I’m dubbing the Apocalyptic Narcissism—the ultimate “Me” Decade trip, where even the end of the world becomes a selfie.

Let’s start with the first panel, a desert of chaos that looks like Hieronymus Bosch got drunk with Goya and decided to crash a Mad Max audition. A giant, rotting head—its eyes bulging, its mouth a cavern of despair—looms over a battlefield where skeletal soldiers on horseback charge through a haze of smoke and ash. In the sky, a moon bleeds fire, and a burning zeppelin spirals downward like a dying dragon. There’s a castle in the distance, half-crumbled, half-dreamed, and a figure in a red cape—Dalí himself, no doubt—stands on the edge, chin in hand, as if to say, “What a mess, but what a beautiful mess.”

Salvador Dalí - Dnipro Summer I.

The second panel shifts gears but not tone: a long, sandy road stretches toward a baroque palace, flanked by a river where boats bob like toys in a child’s bath. The sky is a swirling nightmare of airships, balloons, and floating spheres, all of them caught in a storm of their own making. Two figures—a man and a woman—walk the road, their shadows stretching like accusations, while behind them, a cavalry charges into oblivion. It’s Ukraine, sure, but it’s also everywhere and nowhere. It’s the Dnipro River, but it’s also the River Styx.

The curators at MoMA want you to think this is a “timely” work, a “meditation on conflict,” a “cry for peace.”

Balderdash!

They’re projecting their own liberal pieties onto Dalí’s canvas, as if he were some kind of editorial cartoonist for The Nation. Dalí doesn’t care about your geopolitics, your sanctions, your NATO summits. He’s not here to mourn the Donbas or decry the Kremlin. He’s here to laugh—cackle, really—at the sheer, unadulterated lunacy of the human race. Look at that giant head in the first panel. It’s not a symbol of war’s victims. It’s a symbol of war’s ego. That’s us, folks, our collective id, bloated and decaying, staring at our own destruction with a kind of horrified fascination. Dalí’s saying: You think this war is about territory? About ideology? About freedom? Ha! It’s about you, staring into the abyss and seeing your own reflection—your own Apocalyptic Narcissism. You’re not fighting for a cause. You’re fighting to feel alive.

Salvador Dalí - Dnipro Summer II.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. Wolfe, you contrarian crank, how can a painting about a war not be political? Isn’t Dalí at least taking a jab at the aggressors? Isn’t he showing the horror of conflict? Sure, there’s horror here—plenty of it. But Dalí’s horror isn’t moral. It’s existential. He’s not judging. He’s observing. That red-caped figure in the first panel isn’t weeping for the fallen. He’s studying them, like a scientist peering through a microscope at a particularly fascinating species of bacteria. Dalí’s war isn’t Russia versus Ukraine. It’s humanity versus itself. And in that battle, there are no winners—only spectators, like the man and woman in the second panel, walking calmly down that road while the world burns behind them. They’re not fleeing. They’re strolling. They’ve seen the apocalypse, and they’ve decided to take a nice little walk anyway. That’s Dalí’s point: We’re all complicit, not because we fight, but because we watch. We turn war into spectacle, into art, into a mirror for our own egos. And Dalí, that old trickster, is the ringmaster of this circus.

Let’s talk about the style, because Dalí’s technique here is pure, unfiltered Dalí—hyperreal yet hallucinatory, a paradox wrapped in a nightmare. The colors are electric: the blues of the sky so vivid they hurt, the oranges of the flames so hot you can feel them on your skin. The details are obsessive—every crumbling brick, every tattered uniform, every feather on the birds circling that giant head. But it’s the composition that grabs you by the throat. The first panel is all verticality, a tower of chaos reaching for the heavens; the second is horizontal, a long, slow exhale, a procession toward nothingness. It’s as if Dalí is saying: Here’s the explosion, and here’s the aftermath. Here’s the scream, and here’s the silence. And in both, you’ll find the same thing: the human race, obsessed with its own reflection, even as it burns.

What’s most striking, though, is how apolitical this all feels. In an age when every artist and their grandmother is itching to “make a statement,” Dalí refuses to play the game. He’s not here to preach. He’s here to provoke. He’s not waving a Ukrainian flag or burning a Russian one. He’s not even waving the white flag of peace. He’s waving the flag of absurdity, of cosmic indifference. The Russo-Ukrainian War, in Dalí’s hands, becomes a stage for a much older drama: the drama of human folly, of our endless capacity to destroy ourselves while gazing lovingly at our own reflection. This is Apocalyptic Narcissism in its purest form—a state of mind where even the end of the world becomes a kind of performance art, a chance to say, “Look at me, I’m suffering so beautifully.”

Tom Wolfe - who did not write this piece - @ MoMA.

And isn’t that the ultimate Dalí move? To take a war—a real, bloody, ongoing war—and turn it into a meditation on the self? The curators at MoMA may want to frame this as a “statement on our times,” but Dalí’s statement is timeless: We’re all narcissists, even in the apocalypse. We fight, we die, we mourn, we paint—and through it all, we’re watching ourselves, marveling at our own drama. Dnipro Summer isn’t about the war in Ukraine. It’s about the war in us. And Dalí, that sly old fox, is laughing all the way to the gallery opening.

So, go see it, folks. Stand in front of this diptych and feel the heat of those flames, the weight of that giant head, the pull of that endless road. But don’t look for answers. Don’t look for politics. Look for yourself. Because that’s what Dalí sees: you, me, all of us, caught in the throes of our own Apocalyptic Narcissism, staring into the void and loving every minute of it.Your Content Goes Here

Tom Wolfe is the last man in America to wear a three-piece white suit unironically and the first to diagnose art-world self-delusion like a peacock wielding a scalpel. From Wall Street to Warhol, he’s seen it all, laughed harder, and written longer. In the grand gallery of modern madness, he remains the docent who won’t shut up—and thank God for it.

Leave A Comment