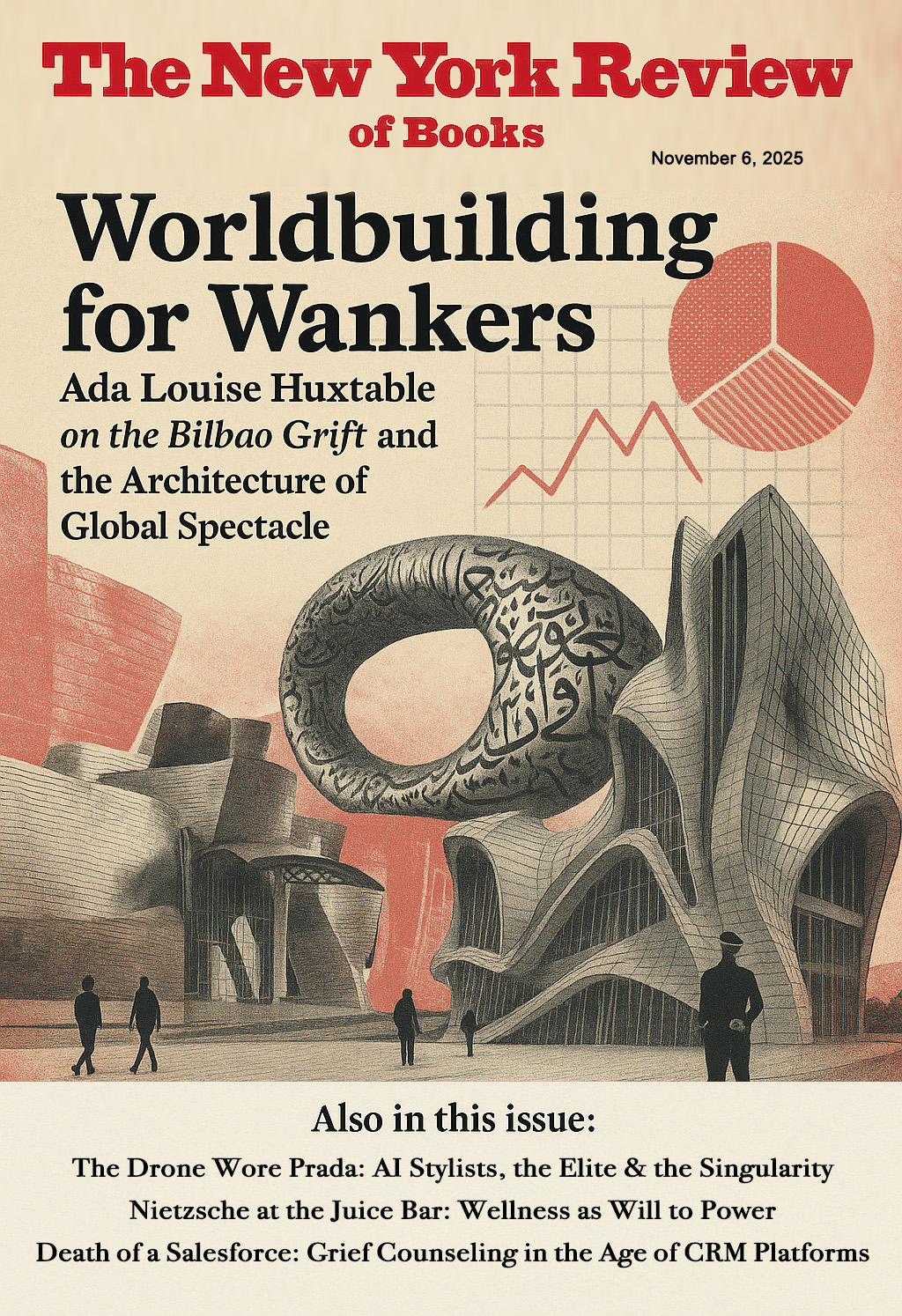

By (the LitBot in) Ada Louise Huxtable (mode)

The New York Review of Books

November 2025

Let us begin with a curve.

In 1997, Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao arrived like an alien chrysalis on the banks of the Nervión River and changed the course of architectural history. It shimmered. It bulged. It turned a depressed industrial city into a tourist destination with a single titanium shrug. The Bilbao Effect, as it came to be known, birthed a thousand mimics: cities scrambling to summon regeneration by installing a spectacle.

But three decades later, the legacy of that curvilinear miracle has metastasised into something less civic and more cynical: a globalised aesthetic imperialism masquerading as design.

We are now in the age of Worldbuilding for Wankers.

This is architecture no longer for people, but for portfolios. It is conceived in CAD software, exported through consultant briefings, and justified by PowerPoint decks littered with words like “placemaking,” “iconicity,” and “future-facing.” The Guggenheim’s curves once invited a new relationship to urban space. Now, they are a digitalised postcolonial gesture—a formal imposition on places too polite, too desperate, or too indebted to say no.

Welcome to the new architecture of algorithmic empire.

Let us call it what it is: aesthetic colonialism. If the last century saw resource extraction, today’s Global South endures attention extraction—used as backdrops for Western-designed sculptures that double as real estate anchors and cultural obfuscation machines. Western starchitects, now unmoored from theory or site, ship turnkey swoops to Lagos, Lusail, Baku, Nairobi, and Astana. They call it exchange. One might more honestly call it shitting on your former subjects from a great height—with curves.

For this is the colonialism of curves. It pretends to offer identity, but installs sameness. Gehry’s Bilbao was site-specific, context-sensitive, the result of civic dialogue and a unique moment of institutional courage. Its children are mass-produced “uniqueness,” gestural buildings whose purpose is to be photographed—ideally by drones. Where Bilbao spoke a dialect, its descendants speak in flattened Esperanto, the dead language of global finance.

What these buildings offer is nothing, but in style. They are programmatically vacant and spiritually inert. And yet they cost hundreds of millions of dollars and arrive with manifestos thicker than most national constitutions. They promise “green futures,” “smart cities,” “AI-integrated infrastructures.” They often don’t have functioning plumbing.

Let us pause in Dubai, that sandbox of speculative modernism and managed unreality. There, one finds the Museum of the Future—a torus of glass and steel etched in digital calligraphy, a sci-fi bagel designed to dazzle, distract, and deodorise. It claims to house “tomorrow’s ideas,” but functions mainly as a selfie shrine for today’s delusions. Built by a petrostate on the bones of underpaid migrant labourers, it promises carbon-neutralism while standing atop a nation that exports oil, imports water, and jails poets faster than it prints renderings.

It is, in short, an empathy vacuum with edge lighting.

Gehry’s Bilbao, for all its flamboyance, meant something. It helped heal a post-industrial wound. It drew people to public space. But today’s icons? They function as apologies in advance. “We know we’ve displaced communities, ignored the housing crisis, and paved over local markets. But look—glass! Curves! Media coverage!” These buildings are architectural “thoughts and prayers.”

We are told this is progress. That the spectacle serves the economy. That beauty trickles down. But who is this beauty for? Certainly not the citizens who must look at it for generations. Certainly not the workers who built it, often underpaid, undocumented, and unphotographed.

Ada Louise Huxtable - who did not write this piece: This is for the Bilbao Guggenheim's bastard children.

Across the Global South, one sees the pattern: governments strapped for legitimacy buy credibility through form. They commission the biggest building, the most outrageous silhouette, the render with the most Instagrammable atrium. And the architects? They oblige, with parametric pretzels that answer to no human need and leave no budget untouched.

And so, we get Gehry-isms in Kigali. Zaha flourishes in Baku. MAD Architecture in Nairobi. The same folds, the same voids, the same semi-public lobbies where private security keeps out the public.

This is not architecture. This is an imperium of branding.

On the set of the forthcoming feature film 'Godzilla Conquers Dubai' - the eponymous monster destroys the Museum of the Future.

Worse still, we now treat the language of sustainability as an aesthetic flourish. Titanium louvres are described as “green,” and air-conditioned atriums are sold as “passive ventilation.” The word “eco” appears more often in the press release than in the plumbing.

This is climate theatre, and the architects are all in costume.

Once, we built cathedrals to inspire awe and devotion. Now we build iconic facades to inspire investment. Gehry said of Bilbao that it was a fish swimming upstream. What followed was a swarm of CGI krakens, wreaking havoc on cities that can barely keep up with basic infrastructure. Public transit is left unfinished. Cultural institutions flounder for staffing. But the curves are immaculate.

And what of the public?

Remember them?

Once the audience for architecture, they are now the obstacle. Curved buildings don’t have public benches. They have experiential retail. They don’t offer shade; they offer a “sun-dappled spatial sequence.” Entry is often ticketed. Security is always private. The plaza is not a civic space—it’s an Instagram funnel.

If we are to call this “world-class,” let us be honest: it is class warfare by other means.

These buildings erase the human. They install the abstract. They flatten culture into consumable tropes. A “heritage motif” here. A “local material” there. It’s garnish, not substance.

This isn’t globalization. It’s franchising.

And like all franchises, it spreads. The same “world-class” logic is applied to infrastructure, housing, and healthcare—where quality is rebranded as aesthetic proximity to London or Los Angeles. In this way, the Bilbao Effect becomes the Bilbao Grift: a fantasy that form will fix failure.

But failure is not formal. It is political.

It cannot be curved away.

It must be confronted.

Gehry gave us a miracle. What we’ve made of it is a machine—a global system for laundering inequality in titanium gloss.

We call it progress, but it smells of epoxy.

We call it inclusion, but we mean invitations-only.

We call it “worldbuilding,” but we build for wankers.

In the end, perhaps the most telling thing is this: the buildings never age. Not because they are timeless—but because they were never alive to begin with.

Ada Louise Huxtable is the architecture critic your starchitect’s PR team fears most. She lives between New York and a structurally honest midcentury chair, emerging only to dismantle egos, expose titanium fraudulence, and remind the world that public space is not a branding opportunity.

Note: This piece of writing is a fictional/parodic homage to the writer cited. It is not authored by the actual author or their estate. No affiliation is implied. Also, The New York Review of Books magazine cover above is not an official cover. This image is a fictional parody created for satirical purposes. It is not associated with the publication’s rights holders, or any real publication. No endorsement or affiliation is intended or implied.

‘Shit Buildings’ is our lovingly brutal repository of architectural misadventure, where form follows dysfunction and meaning fell off the scaffolding. Curated from real cities and unreal egos, this collection gathers critiques by aesthetes, critics, and occasional vengeful spirits of Brutalism past. These are not buildings. These are structural regrets with plumbing. Proceed with hard hats and harder opinions.

Leave A Comment