I. Amuse-Bouche

Milan Hrubý had been cooking in the same greasy kitchen for over two decades, and loved what he did (for the most part). Sure, there were tough seasons when he’d wanted out. But never like this.

U Vepře had been a modest success. Tucked just off a side street in Prague 3, it was the kind of restaurant that food bloggers described as a ‘hidden gem,’ which meant the lighting was bad and the chairs were uneven, but the food kept you coming back. Milan’s pork neck stew had once made a Dutch tourist cry. His kulajda had been featured in a magazine, albeit one dedicated to mushrooms.

Business had been good enough that Milan ended up doing something he never thought he would: he took out a loan. A large one. He planned to expand—open a second location in Vinohrady with exposed brick, minimalist light fittings, and all the other nonsense that seemed to attract the phone-camera generation.

He signed the documents with a hand that smelled of garlic and old ambition.

A week later, the gangsters came.

Tonda ‘Štika’ Vávra was a compact man with a boxer’s nose and a new-money tracksuit. He hadn’t bothered to book a table for himself and his party of four (the other three being exactly like him but 20 years younger and three times the size).

One might say that he wasn’t exactly there for the soup.

“We need storage,” Štika said, looking around the cellar like a man assessing livestock. “Nothing much. Just a few crates now and then. And your delivery schedule’s perfect. Regular. Discreet. You’ll barely notice us.”

Milan said nothing. He didn’t have to. Štika continued.

“You get a cut, of course. And protection. But mostly you don’t end up as one of your ingredients.”

That night, Milan found himself desperately re-reading the loan documents over a bottle of Becherovka. In clause 14B, buried between “renovation milestones” and “equipment depreciation schedules,” he stumbled on something useful.

In the event of demonstrated market failure beyond the borrower’s control—defined as a drop in net revenue of 70% or more sustained for six consecutive weeks—the loan will be considered unrecoverable and insured against default.

He stared at the sentence for a long time. Then he poured himself another drink.

If success had led him here, perhaps failure was the only way out.

II. Entrée

The new menu was unveiled quietly, without fanfare.

Gone were the pork knuckles and slow-braised duck. In their place: Deep-Fried Dog (Tofu-style), Durian Porridge, Boiled Lung in Its Own Mucus, and something simply called The Surprise Option, which was never the same twice and often came with a waiver.

Milan also redecorated. The cheerful pig mural was painted over in hospital green (mixed with burnt umber) and he then proceeded to distress it with sandpaper, soot, India ink, and several rolls of industrial-strength masking tape. The lights were replaced with buzzing fluorescents that flickered just enough to give you a headache. The music alternated between a loop of dental drill sound effects and Czech radio from 1994.

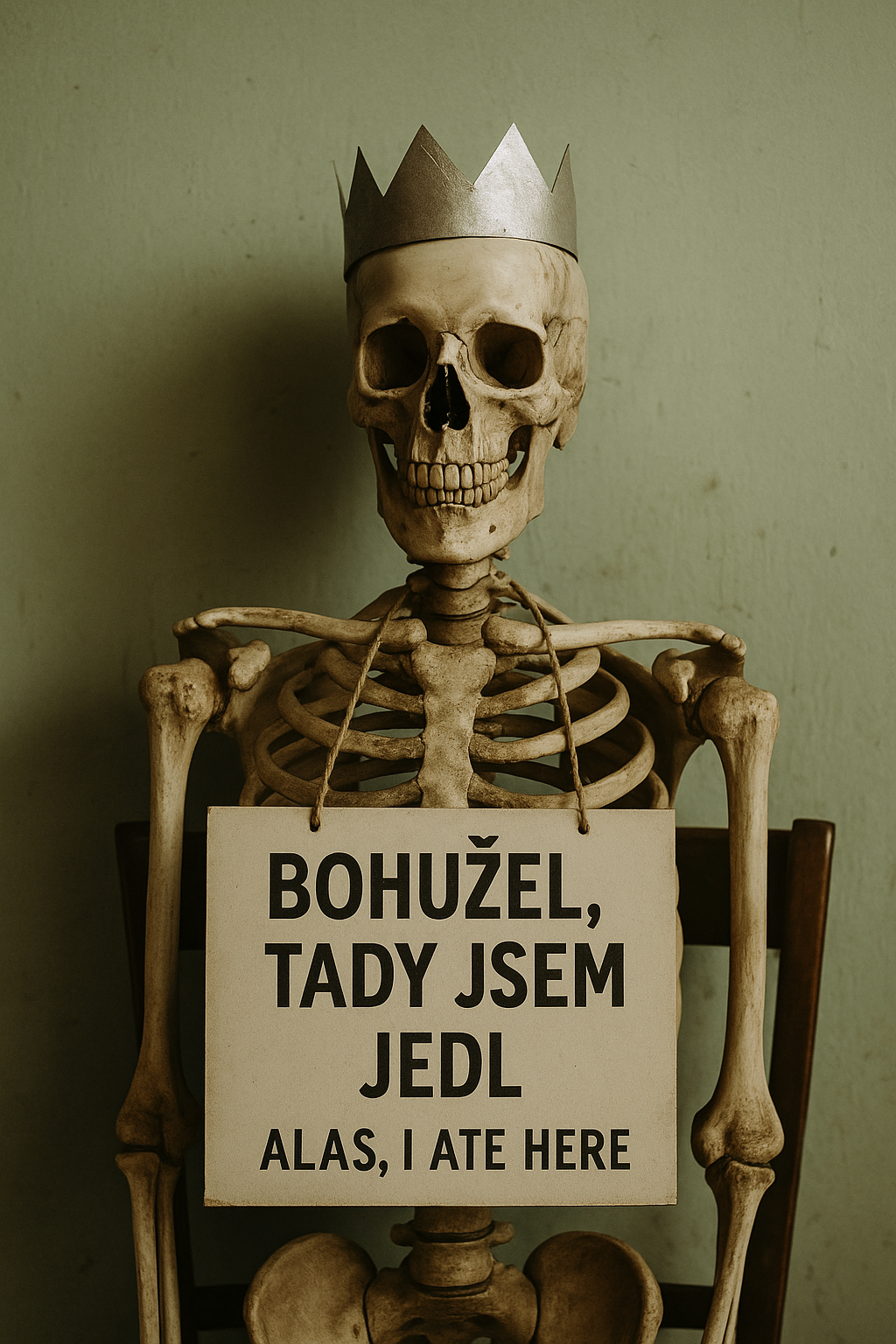

In the corner, a human skeleton—purchased legally, Milan insisted—sat slumped against the window in a crooked paper crown. Around its neck hung a cardboard sign: Alas, I Ate Here.

At its feet, on a cracked porcelain platter, were three taxidermied rats with glassy eyes and greasy fur. The accompanying sign read: Locally Sourced (Found in the Kitchen). Served Fried, Boiled, Fricasseed, or Raw Sushi Style on Request.

For the first few days, customers fled. A family from Brno left mid-meal. A German couple threatened to report him to their embassy. Milan felt a flicker of hope. It was working.

Then the influencers arrived.

One TikTok food critic called it “culinary masochism at its finest.” Another dubbed it “anti-capitalist gourmet.” Lines began to form. Tourists took selfies with the skeleton. (One American seemed to stare at it dreamily for a long time before asking if he could rent it as a prop for an ‘exotic home movie’ to be shot on his smartphone in his hotel room.) A BuzzFeed headline read: “We Tried Prague’s Worst Restaurant—And Loved It!”

Milan watched in horror as his revenue tripled. The insurance clause shrivelled with every grotesque success. Even Štika backed off.

“Too much attention,” he muttered over the phone. “We’ll find somewhere quieter. But listen—if things ever nosedive, if the circus dies down—we’ll be back. This place still owes us a favour.”

Milan hung up and stared at the wall. He’d failed at failing. And now he was trapped by success, with ruin waiting just behind the next bad review.

III. Main Course

By the time the third table had applauded their Blood Soup with (Used) Chewing Gum Reduction, Milan had stopped flinching.

He peered out from the kitchen hatch, past the wall of carefully curated mould-spattered effect wallpaper and into the dining room—a former communist-era dental surgery, left largely untouched, piping and all and bought for a song. (The previous owner had even delivered it for free.)

A Swedish couple were taking photos beside the skeleton. Soon after, the woman bit into something grey and steaming. She moaned loudly, and said, without irony: “It’s like if Michelin did a collab with a cockroach—but in a good way.”

Milan returned to his duties. The sous-chef had passed out hours ago in a dry-heaving heap beside the durian peel bucket. The dishwasher was taking a nap in the walk-in fridge, spooning a bag of frozen rabbit livers. None of it mattered. A line of diners stretched down the block, Instagramming each other’s trauma like it was a birthright.

He sat at the prep bench and stared at the order slips. Someone had ordered three servings of Deconstructed Bile, along with two Smoked Lung Parcels with Goat Urine Nectar & Glue Fondue. And a table of German food critics wanted to try The Surprise Option (which, tonight, meant a hasty call to the Municipal Byproduct Facility).

Milan laid his hands flat on the cutting board. He tried to remember what it felt like to cook with joy. Or even contempt.

Now there was only fatigue.

He just wanted out. But apparently, one couldn’t serve shit without someone calling it dessert. As soon as he thought it, he wondered: was there any line he couldn’t cross? Any threshold so repulsive, so viscerally inimical to the tongue, that every last member of the human race would simply say no?

He pictured himself plating actual dogshit on a matte-black ceramic tile, garnished with a sprig of parsley and a single edible flower. Perhaps a smear of sheep vomit jam. Surely—surely—that would be too far.

Alas, he then remembered looking up the word scat a few years ago, after coming across it in an interview with a New York gallerist who had described their Berlin experience as “emotionally clarifying.”

Milan, somewhat desolately, turned back to the prep bench and resumed slicing fermented tripe.

It was just past midnight when the door opened and a quiet hush fell over the dining room. No music, no sound but the creak of the old hinges.

The man who entered wore a dark tailored overcoat and gloves. He took a seat at the rat table without asking. The staff recognised him, but didn’t dare speak his name. They only called him Pan Belan.

Roman Belan had once run half the kitchens in Smichov. Before prison. Before politics. Before whatever arrangement now let him move unbothered through the city with the air of someone who’d bought it outright and leased it back to the mayor.

He was served a dish Milan had only added to the menu yesterday as a joke: Veal Tartare with Flies. The flies were candied. The veal was real. Roman Belan took one bite, chewed, and smiled.

He beckoned Milan over.

“You’re not just a cook,” he said, voice low. “You’re an alchemist.”

Milan stayed silent.

“We’ll keep this place,” Belan went on. “And we’ll open more. Berlin. Amsterdam. New York. Maybe Tokyo, if they’re ready. You get to keep thirty percent. I offer the ‘security’—economic and less tangible—for being part of my worldwide operations. Fair?”

Milan opened his mouth. Nothing came out.

Roman raised his glass of durian martini.

“To pain, Milan. The only honest flavour left.”

IV. Digestif

The next night, a livestreamer wept openly while eating Canine Carbonara. She whispered, “This changed me,” as the comments poured in.

Milan watched from the kitchen, silently plating something worse for the next course.

Apparently, all you had to do was serve an agonised cry of the soul with some nuts and seeds and garlic chips, and someone would pay for the privilege.

He wondered if that might make a good opening line to a book on Czech cooking—something Waverley Root might have penned if he’d been into scat as much as fine dining. (Or that bone-fetishising American patron who was in before.)

Speaking of which, maybe he could hire out the skeleton—which he’d taken to calling ‘Thaddeus’ after the Patron Saint of Lost Causes—as a side business? It might allow him an income stream not tied to Belan, something he could quietly accumulate to ultimately fund a way out of the madness, such as starting a traditional bistro in some no-name backwater near the Polish border.

Preferably somewhere without gangsters or wi-fi.

Or people who dreamily gazed at skeletons with erotic intent.

Or people who knew what scat meant.

© Anton Verma, 2025

Leave A Comment