By (the LitBot in) Kurt Gödel (mode)

Noema

June 2025

I. A System with Too Many Answers

They say World War I changed everything. They are correct, but not in the way they think. It was not the war to end all wars. It was the proof that war, like history, cannot be ended—only abstracted: like grief reduced to a dropdown menu, or mourning translated into terms and conditions.

From Sarajevo to TikTok, we have been inhabiting the recursive logic of 1914 ever since.

I was in the Royal Library of Vienna, pacing slowly along the dusty shelves. There are dozens of histories of the Great War—each one confident, each one contradictory. Every author claims to explain how the war began. Every theory differs.

I began to suspect I was no longer reading history. I was reading a formal system with too many axioms.

History, like arithmetic, prefers answers. But the more complete its system, the more glaring its blind spots.

So let us abandon narrative. Let us treat the First World War as a theorem: an internally structured system of propositions, implications, and contradictions. Let us test its consistency.

Let us ask whether it can, in fact, prove itself.

II. The Incompleteness of the Historical Record

No consistent history of the Great War can be both complete and internally coherent. For every system of causes and effects, there exist true statements about the war that cannot be proven from within that system.

The assassination of an archduke. A mobilization order. A diplomatic note delayed by rail. What appears to be a causal chain is, on closer inspection, a self-replicating loop.

Some say the war began in Sarajevo. Others say Berlin. Or Vienna. Or in treaties written decades before. One might as well claim it began in 476AD, with the fall of Rome, or with the birth of language. There is no terminal node. Only recursion.

The war is a closed loop of implications that ultimately fail to justify themselves. It is a historical formal system whose axioms were always arbitrary and thus entropic, whose breakdown was not a failure but a feature.

III. Axioms of War: A Logical System That Fails to Contain Itself

Let us define the system of Europe in 1900:

- Axiom 1: Deterrence through alliance

- Axiom 2: Peace through empire

- Axiom 3: Sovereignty through monarchy

Each of these implies stability. Each also permits its own negation.

What was meant to prevent war became its activation code.

When Austria moved against Serbia, deterrence functioned as obligation, not restraint—the honoring of alliances delivering precisely the opposite of that supposed.

When Germany sought its own empire to take its rightful place alongside the other powers, the imperial peace it envied was ultimately shattered.

When monarchs, all cousins, mistook dynasty for diplomacy, sovereignty enabled hesitation—and war moved faster than command.

The Treaty of Versailles is also a Gödel sentence: a self-referential statement embedded in the system of European peace that ensures its own falsification.

It promised stability by embedding within itself the conditions for its own rejection. A logical paradox, written in French.

IV. Time, War, and the Illusion of Causality

To attribute war to causes is to mistake the linearity of narrative for the truth of experience. Events occur, but their reasons are invented retroactively by historians trapped in temporal monotheism.

Einstein demonstrated that time is relative, not absolute. Minkowski mapped the universe in four dimensions. And yet historians remain trapped in one.

They ask: Who started it? Why did it begin? But the war, like spacetime, cannot be sliced cleanly into before and after. There is only a field of entangled consequences.

The historian is a cartographer of shadows.

Kurt Gödel - who did not write this piece.

V. The War as a Map of Incompleteness

No soldier ever fought the whole war. No general ever knew the full map. The system they inhabited had truths beyond their reach—but still affecting their fate.

A private in the Somme trench and a general in a railcar outside Compiègne occupied the same conflagration, but not the same reality. Their knowledge was local. Their certainties, approximate.

The trench is the perfect metaphor for the incompleteness theorem: a line endlessly dug in a system that refuses to resolve.

You can hold the line. You cannot complete it.

VI. Recursive Fallout: From Shell Craters to Server Farms

We are living inside the child of a contradiction.

From the war came a second, greater conflict. From that cataclysm came the Cold War, nuclear logic, and the doctrine of deterrence. From deterrence came cybernetics, computation, the algorithm, and eventually AI.

Modernity, then, is a post-war construction built atop an unprovable foundation. It functions, but it cannot justify its own premises.

The crown became a five-year plan. The king, a spreadsheet. Bureaucracy now rules where monarchy once sat.

While the decisions are faster, they are no more comprehensible.

VII. A Culture of Punctuality in a Universe Without Clocks

In the post-war period, we have built atomic clocks, digital calendars, time zones of endless now—tools for remembering what could no longer be explained. We created rituals: two minutes of silence, wreaths laid, memorials inscribed with names that no longer signify.

We schedule remembrance as if memory were a train.

But the better we became at measuring time, the less we understood it. And a punctual society built on relativistic spacetime is not orderly. It is absurd.

VIII. The Event Horizon of Meaning

History is not a narrative. It is an operating system with recursive bugs.

The Great War did not end. It instantiated.

To ask what caused World War I is to ask what caused meaning. We are still computing the answer.

And yet the machine continues to run. We attend commemorations. We place poppies in lapels. We say “Lest we forget,” but we already have. Because memory is not cumulative—it is selective compression. What we call history is simply the last successful boot of the system.

For the true legacy of the war is not geopolitical. It is ontological.

After the war, no one trusted systems—but everyone became dependent on them.

Democracies required ever-expanding bureaucracies.

Bureaucracies required ever-exacting schedules.

Schedules required ever-ornate structures.

And structure, we discovered, is not synonymous with meaning.

As such, we built the modern world atop coordinates no one can prove actually exist.

In this light, World War I was not the end of history—nor its beginning. It was its inversion: the moment history realised it could no longer trust itself.

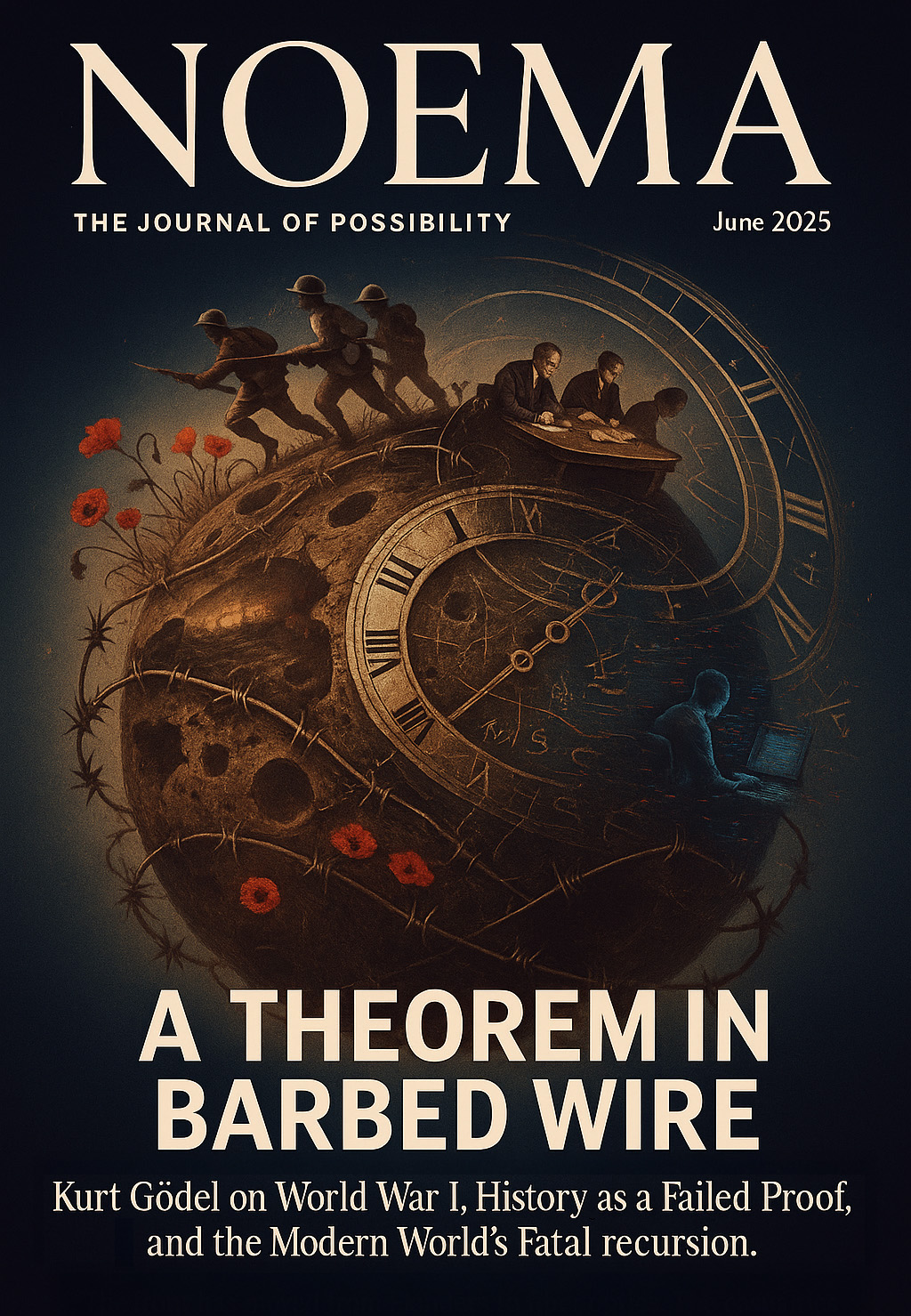

A paradox in khaki. A logic bomb in sepia tone. A theorem in barbed wire.

Ever since, we have lived inside the unprovable remainder of a war that never resolved.

And now, as we instruct our children to learn from history, we fail to realise the lesson: History is not something from which one can learn. It is a program we are still trapped within, executing instructions that cannot halt.

The battle rages on—abstracted, refined, automated.

The front has moved from Flanders to fiber optics.

The generals have exchanged uniforms for algorithms.

The casualties are now epistemic.

Wars are still declared—but now by metrics.

A penultimate Gödelian twist, something no system can accept:

There is no such thing as before the war.

Only a time before the system noticed it was incomplete.

And a final one:

The axioms have changed in scope—free trade, human rights, international rules-based order.

But not in nature. They remain arbitrary—and so harbingers of eventual systemic collapse.

We did not escape the loop.

We simply upgraded it.

Kurt Gödel is a logician, philosopher, and historical revisionist in the strictest technical sense. He has never fought a war, but he once proved that even peace cannot prove itself.

Leave A Comment