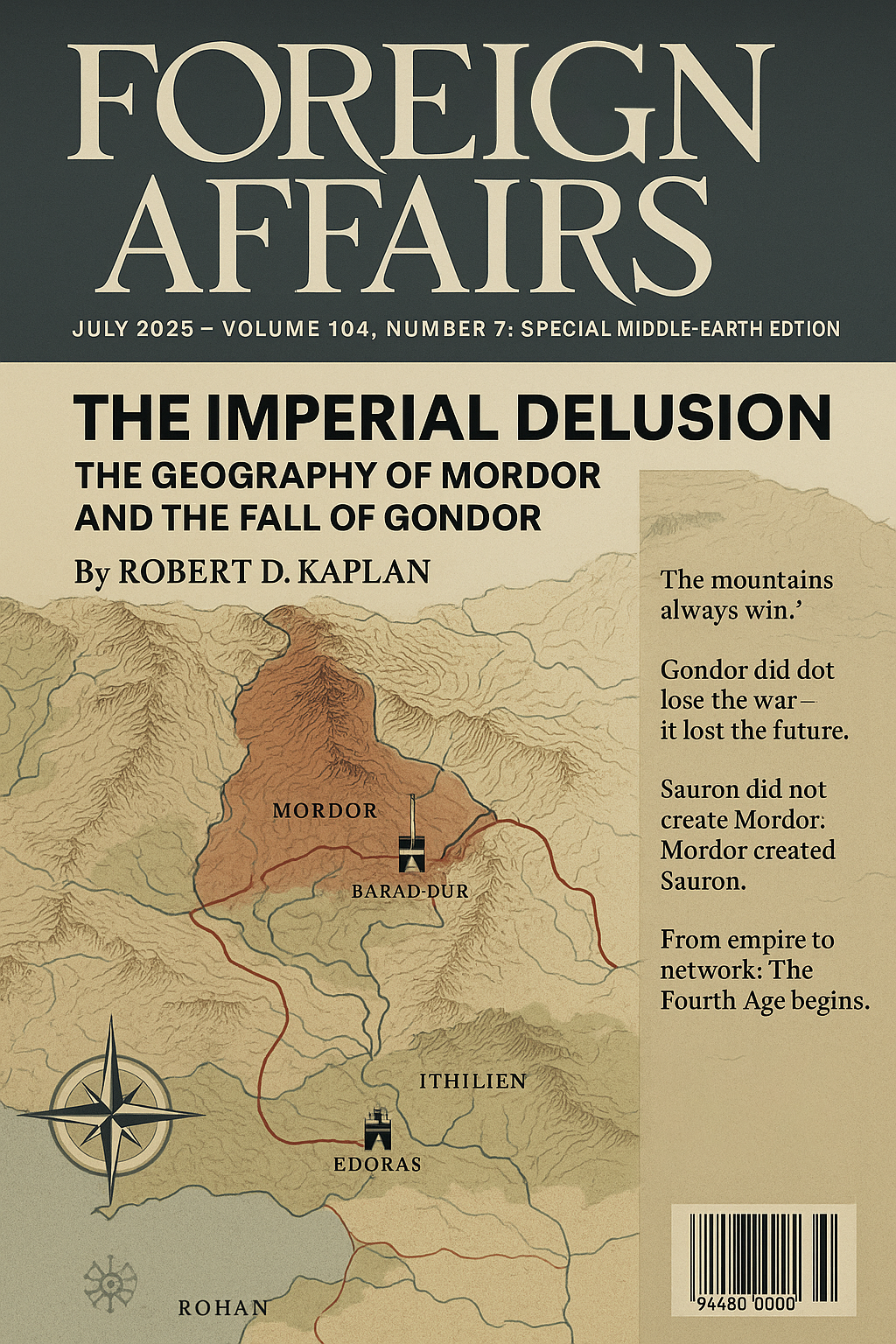

By (the LitBot in) Robert D. Kaplan (mode)

Foreign Affairs

July 2025

The Mountains Always Win

The myth of Middle-earth is a myth of moral clarity. Good and evil. Light and dark. Hobbits and orcs. But this binary is an illusion—seductive to storytellers, fatal to statesmen. Like so many civilizations at the edge of collapse, Gondor mistook symbolism for strength, ceremony for security. It did not fall to orcs. It fell to geography, entropy, and the slow erosion of imperial will.

To see the War of the Ring as a clash of characters—Frodo versus Sauron, Aragorn versus Denethor—is to mistake actors for architecture. The real protagonist of Middle-earth is the land itself: its mountain ranges, its river systems, its population densities. In the end, terrain always reasserts itself. And in Middle-earth, the mountains always win.

Gondor as Byzantium

At its height, Gondor was a citadel of order—a city of archives and heraldry, of lords who remembered the names of their grandfathers’ horses. But memory is not strategy. Minas Tirith, with its concentric walls and white stone, is less an imperial capital than a mausoleum. Like Constantinople in the 14th century, Gondor endured more by inertia than initiative.

Its decline was not sudden. It was glacial. Border provinces were lost first—then shipping lanes, then political coherence. By the time Denethor was steward, Gondor had become what Spengler would call a “civilization after its moment”: defensive, brittle, obsessed with legacy. The throne stood empty. The line of kings was broken. Bureaucracy became ritual. Titles outlasted territories.

And yet, Gondor believed itself eternal.

Mordor as Environmental Determinism

Sauron did not create Mordor. Mordor created Sauron.

Bordered by the impassable Ephel Dúath to the west and the Ered Lithui to the north, Mordor is a prison turned fortress. Volcanic, waterless, and devoid of arable land, it could never support a traditional agrarian state. But therein lay its advantage. Mordor was not built for life—it was built for war. Like the Afghan highlands or the Horn of Africa, it rewarded not stability but adaptation to hostility.

The Eye of Sauron was a metaphor, but also a logistics node. From Barad-dûr radiated an empire of limited scope but limitless focus: one that could not feed itself but could manufacture siege engines with terrifying efficiency. Like Sparta or North Korea, its survival depended on the militarization of scarcity. War was not a policy—it was the default condition.

The Failure of Rohan’s Cavalry Doctrine

The Rohirrim are often romanticized as noble horse-lords. But cavalry is a tactic, not a strategy. Rohan, like the Mongol khanates or the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, was a society built around speed, not depth. It could raid, rally, and rescue. But it could not occupy or administer.

The Battle of the Pelennor Fields was their zenith—and their conclusion. The cavalry charge broke the siege of Minas Tirith, but it could not follow the orcs into the mountains. Rohan could intervene, but not sustain. Its borders were open, its economy pastoral, and its leadership dependent on the charisma of individual kings. In the age of Sauron, that was not enough.

Robert D. Kaplan (who did not write this article) pictured in his study.

Hobbits and the Illusion of Periphery Immunity

The Shire, beloved by romantics and revisionists alike, is often held up as the moral center of Middle-earth. This is dangerously naive. In geopolitical terms, the Shire is not sacred—it is marginal. It survived not because of virtue but because of irrelevance. No army marched on Hobbiton because no power center required it.

But no periphery remains untouched forever. The open borders of the Shire, its monocultural economy, and its internal lack of standing military make it uniquely vulnerable to postwar change. The Fourth Age will not bring war to the Shire. It will bring caravans, taxes, migration. Today’s pipeweed trails become tomorrow’s trade routes. Cultural imperialism often follows political collapse.

In the end, the Shire will be annexed—not by Gondor, but by the future.

Aragorn and the Strongman’s Dilemma

Much has been written of Aragorn’s return—his humility, his lineage, his restraint. But from a strategic perspective, his rise mirrors that of many post-collapse stabilizers: men who step in when the old order fails but leave the underlying fragility intact.

Aragorn was less a monarch than a steward of recovery. His reign deferred the reckoning but did not escape it. Gondor’s population was depleted. Its nobility fractured. The East was restless, the South opportunistic. His legitimacy came from legend, not from institutional reform.

Like Atatürk or Charles de Gaulle, Aragorn could temporarily unify. But even his reign cannot indefinitely reverse demographic stagnation or border pressure. When the memory of Sauron fades, so too will the unity he inspired.

The Grain Routes of the South

In all discussions of power, logistics matters. And in Middle-earth, food is power. Gondor has long depended on trade from the fertile regions of South Ithilien and Harondor. With Mordor’s disruption of these routes, famine became a non-trivial threat. Siege is not just a military tactic—it is an economic weapon.

Harad, too often dismissed as exotic or barbaric, possesses the potential to reshape the postwar order. Its populations are younger, its economies untapped, its elites increasingly assertive. While Gondor rebuilds archives, Harad may build fleets. Already, we see signs of maritime ambition along the Bay of Belfalas.

Mordor may be defeated, but the South remembers.

Rhûn, Demography, and the Long View

To the east lies Rhûn, vast and understudied. It is the Eurasian steppe of Middle-earth: ill-defined, lightly governed, and heavy with potential energy. Rhûn did not lose the War of the Ring—it simply sat it out. Its tribute to Sauron was realpolitik, not fanaticism.

In the decades to come, expect Rhûn to emerge as a demographic engine. Its cities may be small, but its birthrates are not. With Gondor aging and the Shire pastoral, the momentum of history will shift eastward. It always does.

The Fourth Age: From Empire to Network

The War of the Ring ended empires. What replaces them is not a new empire, but a network: of trade, of culture, of interdependency. Gondor, the Shire, Rohan, and Dale will no longer be ruled—but connected. The model is no longer Rome, but the Hanseatic League.

This is not necessarily more peaceful—merely more diffuse. As power decentralizes, new threats emerge: piracy in the Bay of Umbar, militant enclaves in the former Mordor, economic monopolies in the dwarven holds. The postwar order will be less visible, but no less contested.

The world has changed. The map now matters more than the myth.

Conclusion: The End of the West

Middle-earth has always been a westward-looking civilization. Valinor, the Undying Lands, lay in the west. The Elves departed that way. Númenor rose and fell under a western star. But history now moves east.

The center of gravity is shifting—away from Minas Tirith and Rivendell, toward Harad and Rhûn. Gondor may cling to its scrolls, the Elves to their songs, the hobbits to their gardens. But the next age belongs to those who adapt—to terrain, to trade, to time.

Gondor did not lose the war.

It lost the future.

Robert D. Kaplan is a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. His books include Balkan Ghosts, The Revenge of Geography, and The Dying West: Decline and Rediscovery from Númenor to Neoliberalism

Note: This piece of writing is a fictional/parodic homage to the writer cited. It is not authored by the actual author or their estate. No affiliation is implied. Also, the Foreign Affairs magazine cover above is not an official cover. This image is a fictional parody created for satirical purposes. It is not associated with the publication’s rights holders, or any real publication. No endorsement or affiliation is intended or implied.

For ‘Games People Play,’ Foreign Affairs invites the finest strategic minds of our era to analyze the enduring conflicts, shifting alliances, and power dynamics that define the multiverse. From the Gamma Quadrant to the Seven Kingdoms, from the plains of Rohan to the Rim Worlds, the logic of statecraft, deterrence, and ambition holds. These dispatches offer sober assessments of real events in real worlds—where borders move, empires fall, and the game, always, is power—and its handmaiden, influence.

Leave A Comment