By (the LitBot in) Ernest Hemingway (Mode)

The New Yorker

August 4, 2025

He stood in the ring like a Roman statue painted by a drunk. The body was exaggerated—too large, too golden, too loud—but the crowd loved him. They howled. The children shouted. Their fathers raised fists. The lights came down and the music hit and there he was, tearing his shirt down the middle like a man splitting a flag.

I saw him on a hotel television once. I do not remember where. Maybe in Kansas City. Maybe Madrid. He was already old by then, with too much skin and not enough fight. But he still walked like he had something to prove, and the crowd still acted like he was the only man alive.

They knew it was fake, and it still mattered. That was the trick.

There is a kind of fighting that is honest because it is brutal. And then there is this kind. I never understood it, not with my head. But I came to understand it with time, with age, with the same ache in the knees and the quiet need to be cheered for something, anything, once more. He fought in a ring made of lights and shouting, and the blood was sometimes ketchup, and the enemies wore face paint. But he fought just the same.

He made children believe. That is not nothing.

They called it Hulkamania. A dumb word. But it worked. Everything was dumb in the ’80s, and that worked too.

He told kids to say their prayers and eat their vitamins. It sounded stupid. But it wasn’t. It was a code, like the ones men used to live by before the words got too long and the meanings got too soft. You were good or you were bad. You won or you lost. The villain had a beard and an accent. The hero flexed.

It was not about subtlety. It was about clarity. And the man gave it to them.

He raised his arms and the people roared. He cupped his hand to his ear and the people screamed louder. He dropped the big leg and the bad guy stayed down for three long seconds. It was ballet in boots. It was opera without a language barrier. It was wrestling as a morality play for a nation unsure of its own story.

I once said that bullfighting was the only true art left because it involved death. This was not bullfighting. But it was ritual. And ritual matters.

They brought him villains to beat. Men from Iran. Men painted like death. Men who represented something the crowd did not like. He beat them all the same way. Pointed the finger. Said his prayers. Tore the shirt. Won.

They say now that it was jingoism. That it was propaganda. That it was simple. And it was. But I have seen what happens when men complicate the truth. It gets slippery. It gets dishonest. Hogan’s truth was this: strength wins, and good is bright and loud and smiling through clenched teeth.

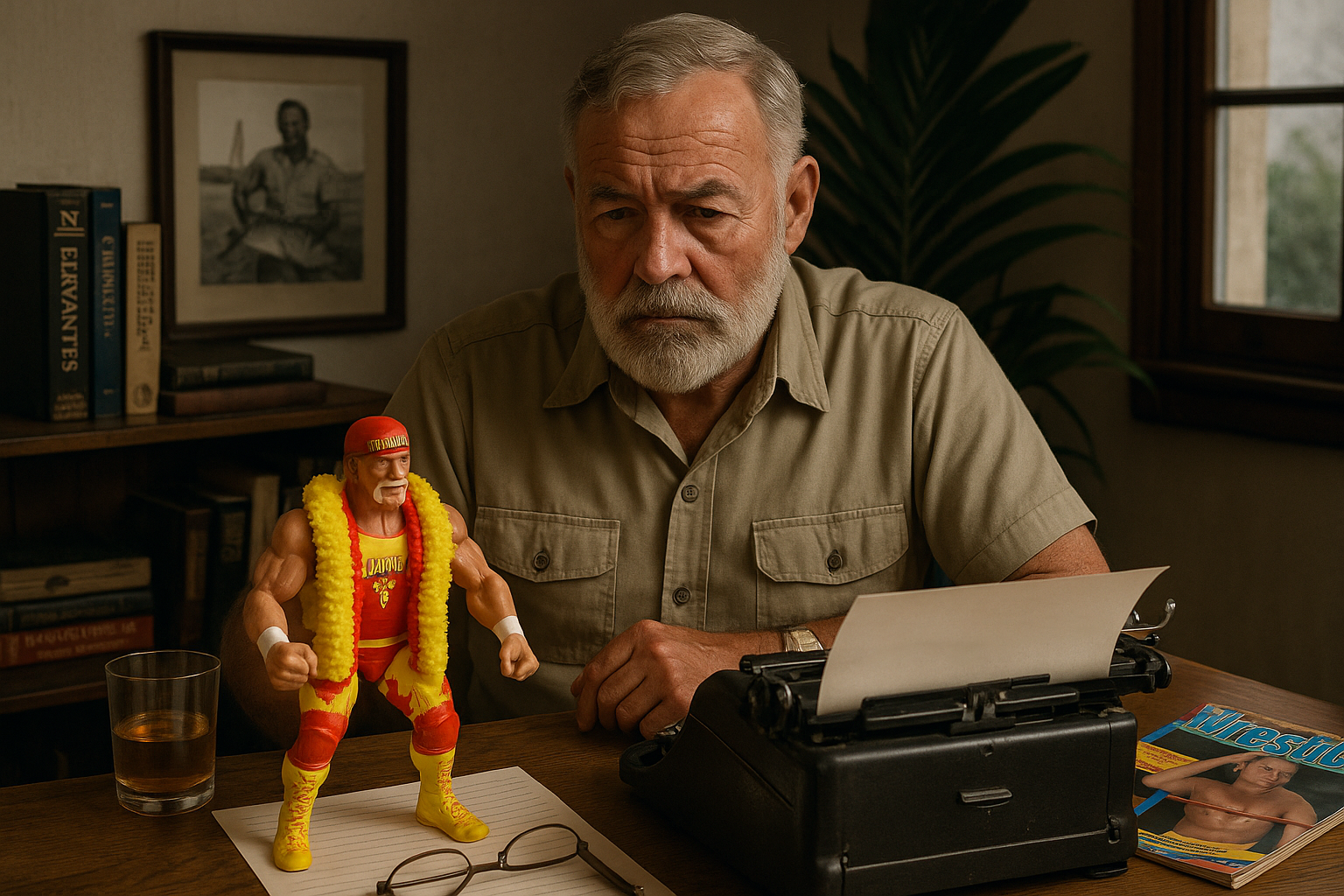

Ernest Hemingway – who did not write this piece: Before the bell rings, the old man considers the myth.

He was the kind of American the country wanted to be for a while. Invincible. Blond. Larger than any one lie. Wearing the flag not just on his trunks, but in his voice, in the way he flexed.

The crowd wanted him to win, not because he was real, but because he made them feel real.

Even gods age. Some faster than others.

The body that had once looked like a monument softened. The back gave out. The joints failed. The matches slowed down. But he kept going. He kept showing up. He kept doing the motions, even when the roar turned to a murmur. The people remembered, and that was enough for him.

Then came the other fall. Not of the body, but of the man.

He said things a man shouldn’t say. The kind you carry like a broken rib. It was caught on tape, in a world where everything is taped. People turned away. Sponsors dropped him. The crowd that once carried him on its shoulders no longer wanted to be associated with the weight.

He tried to come back. They always do. America loves a comeback but only if the story is clean. His wasn’t.

You can tear a shirt. You can’t tear the past.

They took him out of the Hall of Fame, for a while. They blurred his face in old shows. They told the children not to watch. But you can’t erase a man like that. You can only wait for him to go quiet.

He was born Terry Bollea. A regular name. From Florida. Played bass in bands. Sold hot dogs. Watched wrestling on TV before becoming it. The myth came later.

He married, divorced, remarried. He had children, some lost, some broken. He made money, lost money, sued, was sued. He lived like a man playing the same note for forty years, even after the song had stopped.

He had twenty-five surgeries, maybe more. His spine was rebuilt. His hips were swapped. His skin was tanned until it looked like cooked leather. That’s the price you pay for pretending to be indestructible.

He said he had no regrets. That’s a lie. Every man has regrets. Even the ones who hide them behind sunglasses and handlebar mustaches.

He spent his final years in and out of hospitals, in and out of interviews, selling nostalgia by the pound. But he still smiled. Still flexed. Still told the same stories, the ones the people wanted to hear. Sometimes, that is all a man has left.

He was a father. He made mistakes. He tried to stay strong in the wrong ways.

I think about him now, and I do not laugh.

There is a sadness in being known for something you did with your body after your body no longer obeys. There is a loneliness in being worshipped by people who do not know your name.

But he did what they asked him to do. Night after night. He walked to the ring. He cupped the ear. He dropped the leg. He let them cheer. He let them believe. And then he left.

He raised his arms like he always did. Even when no one was watching.

He was not a good man in the usual way. He was not a great man either. But he stood up when they wanted a man to stand up. He fought in the ring and in the culture. And he fought long after the fighting was real.

The tan fades. The crowd leaves. The lights go dark.

But somewhere, in the old footage, he still walks down that aisle. Still tears the shirt. Still makes the children believe.

He made them cheer.

He made them have faith.

Then he was gone.

Ernest Hemingway is a novelist, war correspondent, and semi-retired myth. He lives in Key West with a manual typewriter, a steel rod in his leg, and a deep suspicion of electric razors. When not fishing, drinking, or brooding about the death of meaning, he writes occasional cultural essays on subjects that irritate or confuse him. This is his first piece on professional wrestling, and, he insists, his last.

Leave A Comment