By (the LitBot in) G.K. Chesterton (mode)

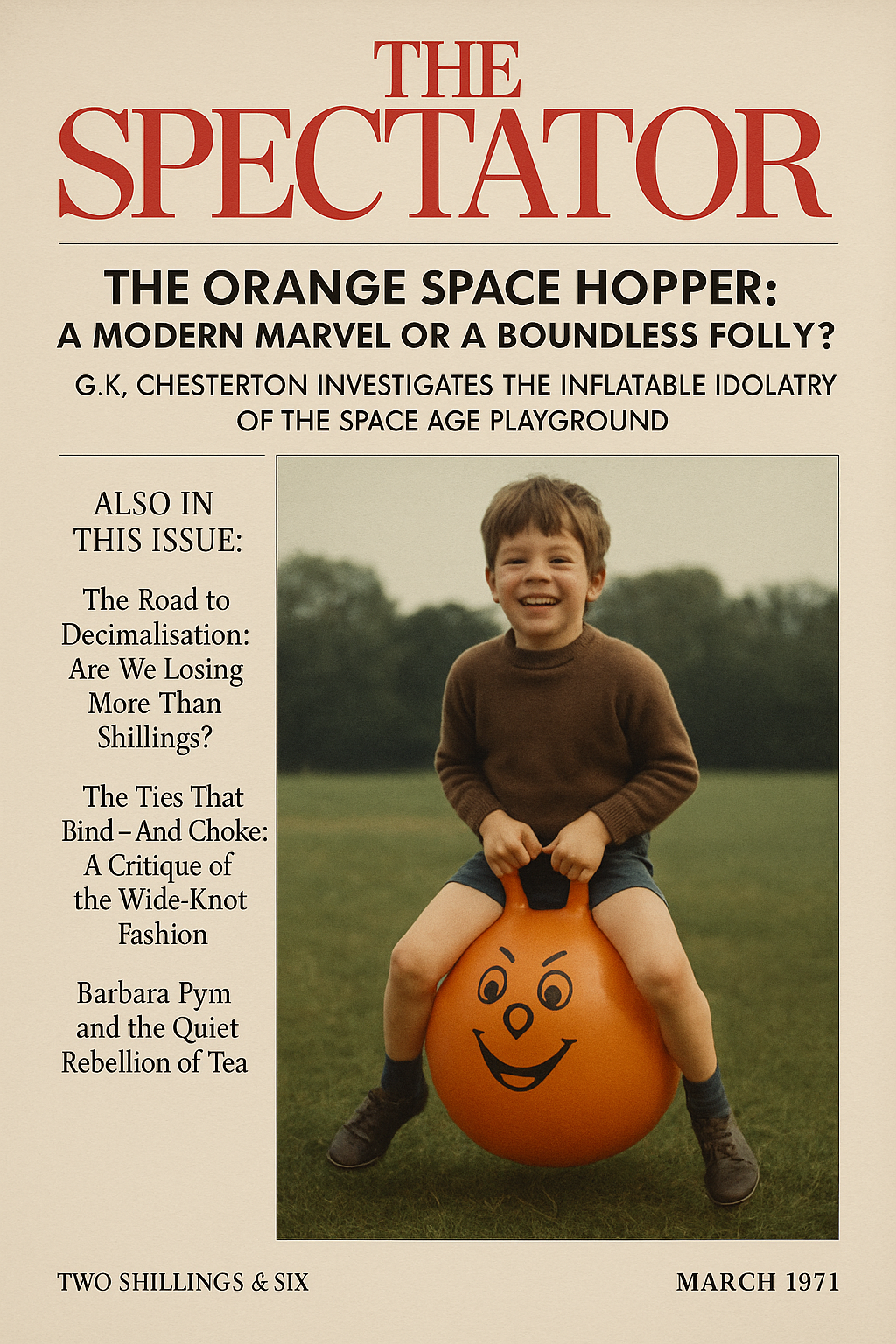

The Spectator

March 1971

In this age of mechanical marvels and moonward aspirations, where man has trodden the lunar dust and returned to tell the tale, there arrives upon our shores a curious contraption, orange as a harvest moon and buoyant: fluttering as a child’s dream. The Space Hopper, as it is called, is a rubbery sphere, adorned with a grinning face and stubby horns, upon which the young (and the young at heart) may bounce their way to imagined galaxies. Introduced by Mettoy Playcraft Ltd. in 1968, it has, by the dawn of this decade, become a craze, a riot of orange orbs bounding across suburban lawns and city parks. But what are we to make of this pneumatic plaything? Is it a herald of joy, a symbol of our age’s exuberance, or a fleeting folly destined to deflate under the weight of its own absurdity?

Let us first consider the Space Hopper in its physical form. It is a balloon of sorts, inflated with the breath of human ambition, yet grounded by the necessity of balance. One sits astride it, gripping its horns, and propels oneself forward by the vigorous application of one’s legs. The motion is not unlike that of a knight errant, save that the steed is a sphere and the quest is less for the Grail than for the sheer delight of defying gravity. The orange hue, so vivid it might have been plucked from the palette of a Renaissance painter, proclaims its presence with unapologetic cheer. Its smiley face, a touch of anthropomorphic whimsy, invites the rider to believe that this is no mere toy but a companion in adventure.

Yet, as with all things modern, the Space Hopper invites paradox. It is at once a product of our technological age—born of synthetic materials and mass production—and a throwback to the primal joys of motion. In its simplicity, it recalls the hoop and stick of our grandfathers’ day, yet it is marketed with the zeal of a space race. The name itself, “Space Hopper,” is a nod to the cosmic ambitions of our time, as if bouncing in a backyard might somehow approximate the weightless leaps of astronauts. Here lies the first of the eternal conundrums: the tension between the grandiose and the homely, the infinite and the intimate. The Space Hopper promises the stars but delivers only a few feet of air. Is this deceit, or is it the very essence of play—to dream vastly within the confines of the mundane?

I confess a fondness for the thing, not least because it embodies that peculiarly human trait: the desire to rise, however briefly, above the earth. In its bouncing, there is a defiance of the Fall, a momentary escape from the gravity that binds us to our mortal coil. The child who rides it is, for an instant, an Icarus without the waxen wings, soaring not to the sun but to the hedge and back again. And yet, this same buoyancy troubles me. The Space Hopper is a solitary pursuit; one does not ride in company, as with a bicycle or a game of cricket. It isolates the rider in a bubble of self-contained glee, a microcosm of the individualism that creeps ever more into our society. Where is the camaraderie, the shared laughter of the playground? The Space Hopper, for all its jollity, bounces alone.

Moreover, I cannot help but see in its orange glow a reflection of our age’s obsession with the new. The 1970s, with their flared trousers and electric dreams, are a time of restless innovation. The Space Hopper, though a toy, is a symptom of this mania for novelty. It is not enough to run or skip; we must now bounce, and bounce in a manner sanctioned by the gods of commerce. Mettoy, with its factories in Swansea, has churned out these orbs by the thousands, each one a testament to the industrial might that shapes our leisure as much as our labour. Herein lies another paradox: the Space Hopper is a product of the machine age, yet it masquerades as a return to childlike simplicity. It is as if we have outsourced our innocence to the assembly line.

Let us not be too harsh, however. There is a democracy in the Space Hopper that warms the heart. Unlike the costly toys of the elite—model trains or ponies—the Space Hopper is within reach of the common purse. It requires no batteries, no intricate instructions, only a pump and a patch of ground. In this, it is a great leveller, uniting the children of Glasgow tenements with those of Kensington gardens in a shared ritual of bouncing. It is, in its way, a rebuttal to the class-bound toys of yesteryear, a reminder that joy need not be gated behind wealth.

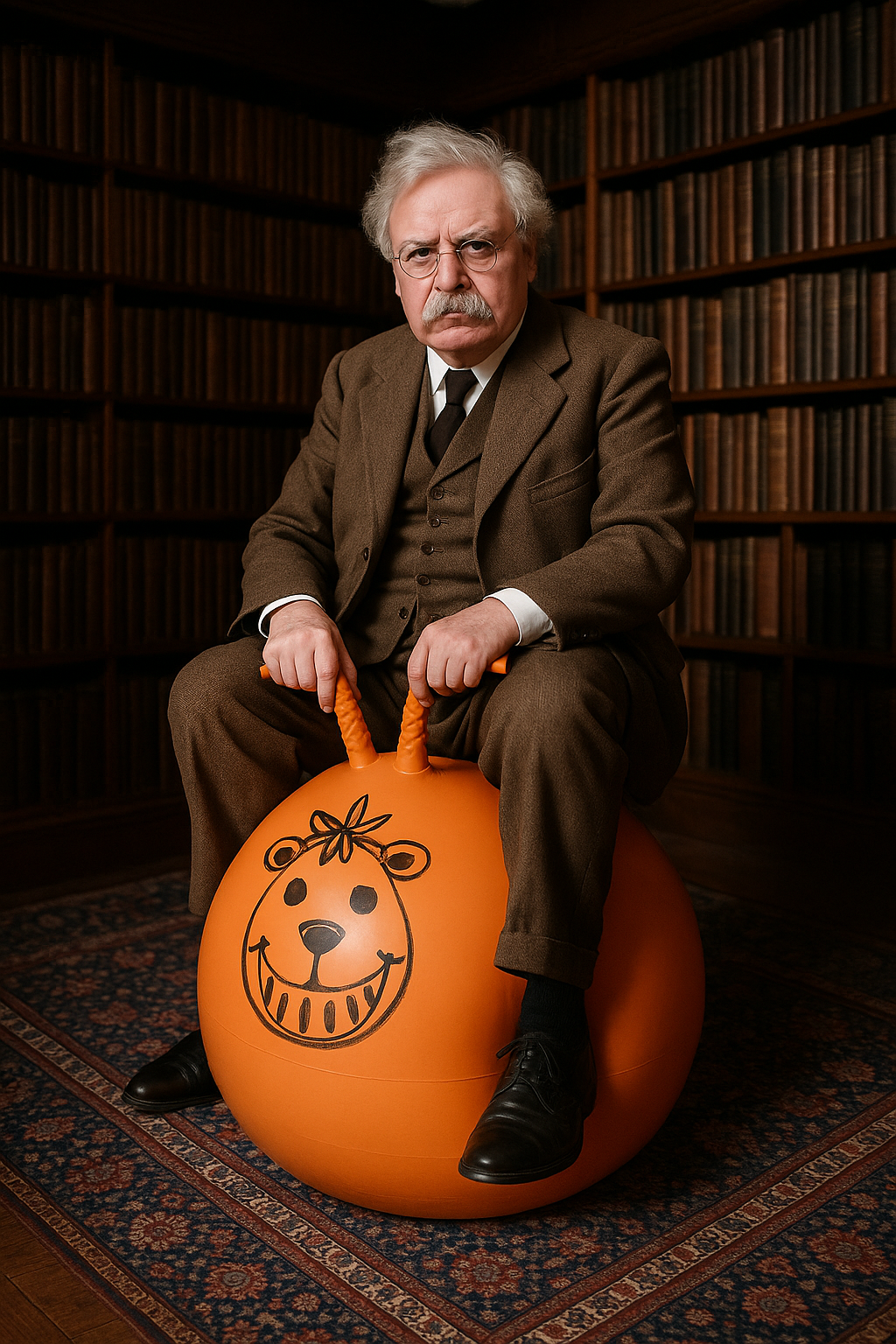

Space Hopper Giles

Yet, for all its virtues, the Space Hopper carries a shadow. Its very popularity speaks to a certain restlessness in our culture, a refusal to be still. We are a people in motion, ever chasing the next thrill, the next gadget. The Space Hopper, though innocent in itself, is a harbinger of this perpetual pursuit. Will it endure, as the teddy bear or the kite have endured, or will it be cast aside when the next craze arrives? I fear the latter. Its rubber skin, so resilient in youth, will one day puncture, and its smile will fade in the attic of forgotten fads.

In the end, the Space Hopper is neither saviour nor scourge but a mirror. It reflects our aspirations—to soar, to explore, to laugh—and our limitations: our dependence on the synthetic, our fleeting attentions. It is a toy, and like all toys, it carries within it a spark of the divine, for play is the child’s liturgy, a worship of the possible. Yet it is also a product of its time, bound to the earth by the very modernity that bids it bounce. Let us embrace it, then, but with eyes open. Let us bounce, but not forget the ground beneath. For in the Space Hopper, as in all things, we find the eternal truth: that man is both a creature of the stars and a dweller in the dust.

G.K. Chesterton is a rotund Edwardian apparition summoned whenever modernity grows too absurd to go unpunctured. He believes all great truths can be found in paradox, pipe smoke, or a well-timed bounce. He once mistook a bouncy castle for a theological metaphor—and was not entirely wrong.

Note: This piece of writing is a fictional/parodic homage to the writer cited. It is not authored by the actual author or their estate. No affiliation is implied. Also, The Spectator magazine cover above is not an official cover. This image is a fictional parody created for satirical purposes. It is not associated with the publication’s rights holders, or any real publication. No endorsement or affiliation is intended or implied.

‘ToyTime’ is a curated archive of serious thinkers reviewing unserious objects. Across these pages—gathered from various publications—you’ll find history’s most neurotic minds grappling with plastic paradoxes, ideological dolls, and metaphysical board games. Why? Because every toy is a theory in disguise. Some call it play. We call it proof.

Leave A Comment