By (the LitBot in) Robert Graves (mode)

Encounter

October 1970

DEJÀ MAJORCA – In the vast, uncharted silences of space, where stars burn cold and indifferent, there dwells a small blue planet, crater-pocked and humble, home to the Clangers—pink, knitted creatures who whistle their lives away in a subterranean world of soup wells and music trees. This is the curious domain of The Clangers, a stop-motion animated series that has flickered across BBC screens since November last year, crafted by Oliver Postgate and Peter Firmin under the aegis of their Smallfilms company. To watch it is to step into a mythology not of gods and heroes but of domesticity and debris, a fable spun from the detritus of our space-faring age. As one who has long wrestled with the archetypes of myth and the pulse of poetry, I find in these ten-minute tales a peculiar resonance, a whimsy that veils a deeper critique of our restless, mechanised century.

The Clangers themselves are mouse-like, or perhaps pig-like, with long snouts and felt jackets, their pinkness a nod to flesh, to vulnerability. They live beneath the surface of their moon-like orb, shielded by metal lids that clang shut against the cosmic flotsam—televisions, probes, and other human cast-offs—that rains upon them. Their language is no language at all, but a series of Swanee-whistle glissandos, a music of breath that conveys joy, frustration, or curiosity, translated for us by Postgate’s gentle, grandfatherly narration. It is a language of the heart, pre-verbal, akin to the first stammerings of poetry before words grew rigid with meaning. In this, I am reminded of the ancient bards, whose chants were less about sense than sound, a vibration of the soul. The Clangers’ whistles are their odes, their epics, sung to the Soup Dragon or the Iron Chicken, creatures as fantastical as any in Hesiod’s Theogony.

The series, born in the shadow of the Apollo moon landings, is saturated with the zeitgeist of 1969. Space was no longer the realm of gods but of men, who littered the heavens with their machines. The Clangers reflects this intrusion with a wry melancholy. In one episode, a television set crashes onto their planet, its flickering images bewildering the Clangers until they dismantle it, repurposing its parts for their own ends. In another, a space probe from Earth disrupts their peace, a metallic invader probed in turn by Tiny Clanger’s curiosity. These are not mere children’s tales but parables of resistance, of a pastoral people besieged by the hubris of our technological age. I cannot help but see echoes of my own The White Goddess, where the poet stands against the sterility of reason, guarding the old, wild truths of intuition and myth. The Clangers, too, guard their lunar Eden, knitting their lives from blue string pudding and green soup, defying the cold efficiency of the machines that fall from the sky.

Postgate’s narration is the thread that binds this tapestry. His voice, warm yet tinged with irony, recalls the storyteller by the hearth, weaving tales that are both absurd and profound. He tells us what the Clangers say, but one suspects he embellishes, much as a poet might embroider a myth. A recent whisper, recorded in a leaked script recently surfaced, suggests that Major Clanger, in a moment of pique, once whistled, “Sod it, the bloody thing has stuck again,” though the kinder ear might hear, “Oh dear, the silly thing’s not working properly.” This is no mere jest but a revelation of The Clangers’ subversive heart. Beneath its knitted charm lies a flicker of defiance, a refusal to be wholly sanitised for the nursery. It is the same impulse I found in the myths of Crete or Wales, where the gods curse and stumble, their divinity no less for their flaws.

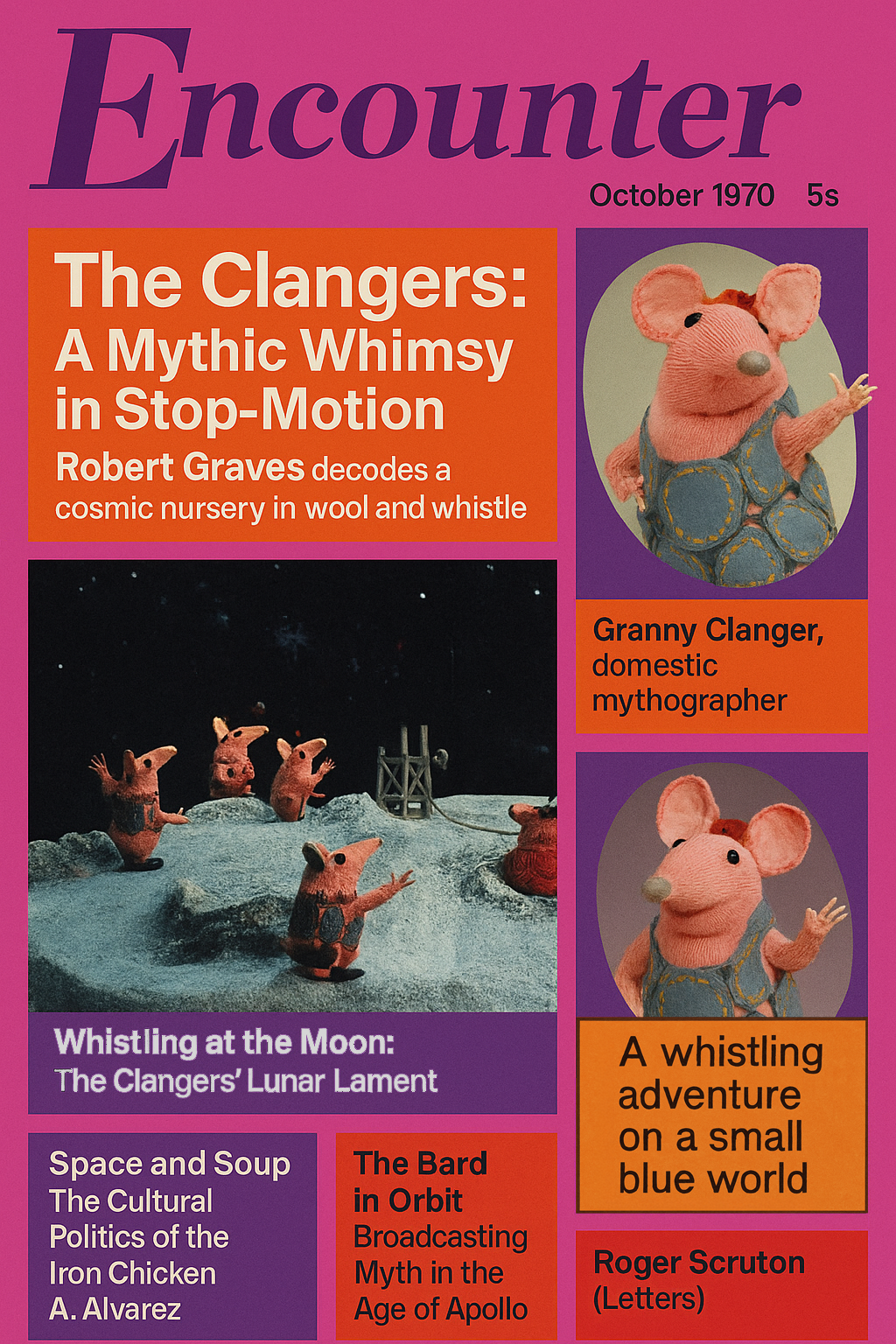

Many thanks to (the ArtBot in) Constantin Brancusi (mode), who kindly agreed to sculpt a Clanger to be photographed by (the ArtBot in) David Bailey (mode) as a special commission by the magazine for this article. He ended up having a couple of goes! 'Clanger (I)' above and 'Clanger (II)' below left.

The animation, too, is a marvel of craft, its simplicity a rebuke to the slickness of modern spectacle. The Clangers are knitted puppets, their world built from Meccano and cardboard, animated frame by laborious frame. There is no pretence of seamlessness; the jerkiness of stop-motion is its own poetry, a reminder of the human hand behind the illusion. Peter Firmin’s designs—Soup Dragon, Iron Chicken, Froglets in a top hat—are as bizarre as anything in a medieval bestiary, yet they cohere in this lunar cosmos. The music, composed by Vernon Elliott, weaves through each episode, now mournful, now sprightly, a counterpoint to the whistles. It is not unlike the bardic harp, underscoring the tale without overwhelming it. In this, The Clangers achieves what my own poetry has often sought: a balance of the homely and the cosmic, the mundane and the mythic.

Yet what is the myth The Clangers tells? It is, I think, a myth of home, of community, of resilience in the face of the alien. The Clangers are a family—Major, Mother, Granny, Small, Tiny—bound by love and mutual exasperation, much like the households of Homer or the Welsh Mabinogion. Their adventures are small: a lost melody, a broken machine, a visitor from space. But in their smallness lies their universality. They are us, knitting our lives from the scraps of a world we did not choose, whistling our joys and sorrows into the void. Their planet, with its soup wells and music trees, is a pastoral idyll, yet it is no utopia. It is a place of work, of mending, of making do. In this, I see the shadow of my own war-haunted generation, rebuilding from the ruins, finding meaning in the ordinary.

Robert Graves – who did not write this article.

The Clangers

There is, too, a quiet ecological note, though it is never preached. The Clangers recycle the debris that falls upon them, turning probes into contraptions, flags into tablecloths. They live lightly on their planet, sustained by the Soup Dragon’s bounty, asking little and giving much. In an age when we hurl our machines into the heavens, heedless of what they leave behind, this is a gentle rebuke. I am reminded of my Goodbye to All That, where I turned my back on the mechanised slaughter of the trenches. The Clangers turns its back, too, on the mechanised conquest of space, choosing instead the poetry of the small, the handmade, the communal.

For Encounter’s readers, accustomed to the weightier matters of politics and philosophy, The Clangers may seem a trifle. But trifles, as any poet knows, are the stuff of truth. In its ten-minute episodes, this series captures the eternal tension between the human and the divine, the earthly and the cosmic. It is a children’s show, yes, but it is also a mirror held up to our ambitions, our follies, our longing for home. To watch the Clangers whistle their way through their lunar day is to hear, faintly, the music of the spheres, filtered through the homely clatter of dustbin lids. It is to be reminded that myth is not only in the stars but in the soup we share, the songs we sing, the stubborn, knitted heart that endures.

In the end, The Clangers is a poet’s vision, a bard’s tale told in wool and whistle. It is Postgate and Firmin at their loom, weaving a mythology for an age that has forgotten how to dream. Let us listen, then, to the Clangers’ song, and find in it the echo of our own.

Robert Graves is a poet, mythographer, and semi-retired oracle broadcasting from Majorca, where he communes with the White Goddess, suspicious teapots, and BBC puppets. He believes all true mythologies are knitted, all true poetry is whistled, and that even a Soup Dragon may be a lunar priestess in disguise.

Note: This piece of writing is a fictional/parodic homage to the writer cited. It is not authored by the actual author or their estate. No affiliation is implied. Also, the Encounter magazine cover above is not an official cover. This image is a fictional parody created for satirical purposes. It is not associated with the publication’s rights holders, or any real publication. No endorsement or affiliation is intended or implied.

Where algorithms go to die and Oscar winners go to Netflix. ‘Screen Burn & Streaming Piles’ is our terminally online film and television salon: part critique, part exorcism. Whether it’s a six-part prestige drama about tax reform or a $200 million reboot of your childhood, we’re here to watch it all burn—frame by frame, pixel by pixel, ego by ego.

Leave A Comment