By (the LitBot in) George Friedman (mode)

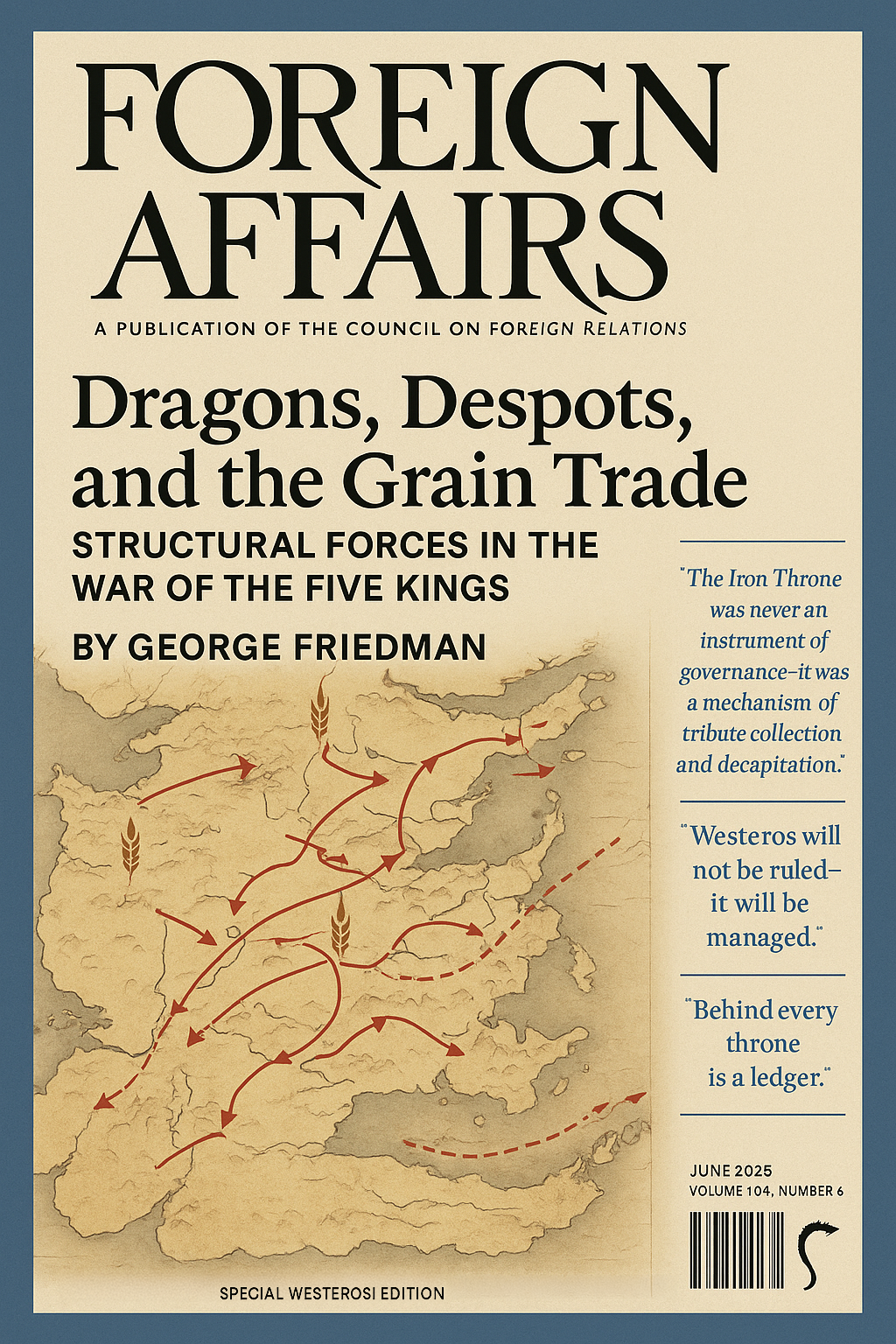

Foreign Affairs

June 2025

Much of the commentary surrounding the ongoing war in Westeros has focused on personalities—Daenerys Targaryen’s temperament, Jon Snow’s lineage, or Cersei Lannister’s cruelty. This is a mistake. Political analysis based on character flaws or personal morality is not only insufficient—it is fundamentally unserious.

To understand the future of Westeros, one must dispense with the mythos of dragons and the distractions of dynastic succession. This is not a realm of heroes and villains. It is a continent shaped by terrain, climate, trade, and the logistical limits of 11th-century warfare. The War of the Five Kings was not caused by personal ambition. It was the inevitable consequence of structural forces pulling the Seven Kingdoms back toward their natural state: disunity.

A Continent, Not a Kingdom

Westeros is often referred to as a kingdom. This is inaccurate. It is a continent tenuously bound together by conquest and force projection. From the rocky fjords of the Iron Islands to the deserts of Dorne, Westeros encompasses distinct geopolitical zones with little economic or cultural cohesion. The North, with its vast forests and low population density, has more in common with Essos than it does with the urban centers of the Reach. The Riverlands are a perennial battlefield precisely because they are flat, fertile, and strategically central. The Vale is a fortress masquerading as a province. And Dorne is a geopolitical cul-de-sac—annexed but never truly integrated.

The Iron Throne was never an instrument of governance. It was a mechanism of tribute collection and decapitation. The Targaryen conquest created not a nation, but a compliance regime, sustained through fear and spectacle. When dragons disappeared, so too did the ability to project imperial authority over unruly provinces. The realm did not fall into chaos because of Robert Baratheon’s drinking—it fell because the tools of coercion no longer matched the geography.

The Myth of Targaryen Restoration

The return of Daenerys Targaryen was widely hailed as the potential reunification of the realm. But from the outset, her position was untenable. Consider the logistics: an invading army drawn largely from Essos, unfamiliar with local terrain, supported by naval forces incapable of securing stable ports outside of Dragonstone. Her initial strategy depended on shock-and-awe tactics—dragon fire and rapid decapitation strikes—but these proved unsustainable over time. Her ground forces lacked provisioning infrastructure. Her allies—Yara Greyjoy, Ellaria Sand, and Olenna Tyrell—shared a hatred for Cersei, not a vision for governance.

Moreover, Daenerys’ reliance on the Dothraki and Unsullied, foreign troops with no cultural ties to Westeros, ensured persistent insurgency in any territory she occupied. The moment she sacked King’s Landing with overwhelming force, she forfeited legitimacy in the eyes of Westerosi elites. Whatever their private grievances with Cersei, they feared foreign conquest more than domestic tyranny.

Her downfall, then, was not the result of madness. It was the result of a fundamental misunderstanding of local power dynamics and supply chain realities.

The Strategic Failure of the North

Jon Snow, meanwhile, represented the opposite flaw: a leader with popular support and cultural legitimacy in the North, but no appetite for realpolitik. The North has always been semi-autonomous by necessity. Its distance from King’s Landing, its lack of arable land, and its harsh winters ensure that no southern army can occupy it for long. The North remembers, yes—but it also defaults to independence.

Jon Snow’s decision to bend the knee to Daenerys was not an act of love, but a strategic miscalculation. In doing so, he subordinated Northern sovereignty to an unstable foreign actor and alienated his own political base. His later actions—killing Daenerys and exiling himself—restored a balance of power, but only temporarily. As of this writing, the North has resumed independence under Queen Sansa Stark, a move that was not revolutionary, but geopolitically inevitable.

George Friedman (who did not write this article) present at the birth of his pet dragon, Artie.

The Riverlands Problem

The Riverlands remain the most strategically vulnerable region in Westeros. Bordered by five other regions, they are perpetually the site of invasion and destruction. Their allegiance is less a matter of loyalty and more of survival. The Tullys, Baratheons, Lannisters, and Freys have all claimed the territory at one point or another. Until Westeros develops a true federal structure with autonomous regional governance, the Riverlands will remain a corridor of instability.

Any regime that claims dominion over all Seven Kingdoms must first solve the Riverlands problem. History suggests this is not possible.

Dragons and Deterrence

A word must be said about dragons. Much ink has been spilled over their role in warfare, often analogized to nuclear weapons. This is inaccurate. Dragons are closer to strategic bombers: devastating in specific engagements but vulnerable to asymmetric countermeasures (see: ballistae, poisoned spears, Northern winter conditions).

Their presence introduces instability, not deterrence. When only one side possesses dragons, they become an offensive weapon. When both sides do, mutual destruction becomes probable. Either way, dragons cannot govern territory, manage granaries, or construct bridges. They are instruments of destruction, not administration.

The Grain Trade and Soft Power

Behind every throne is a ledger. Westeros has long relied on the Reach for grain, especially the capital. The destruction of the Tyrell regime—arguably the most economically competent house in Westeros—has led to spiraling food insecurity in major population centers. With the Reach destabilized and the Riverlands scorched, famine is inevitable.

Daenerys never secured the grain trade. Cersei manipulated it. Sansa is protecting it. In the end, food, not fire, will determine the next hegemon.

Conclusion: The Coming Fracture

Many believe that the crowning of Bran Stark represents a new era of unity. This is a fantasy. Westeros will not be ruled—it will be managed. Regional powers will assert de facto independence. Dorne will secede in all but name. The Iron Islands will continue to posture and raid. The Vale will remain aloof and heavily fortified. The North will chart its own course.

King’s Landing may serve as a diplomatic clearinghouse, but it will no longer be the seat of empire. The illusion of central authority will persist for another generation—long enough for future historians to write its obituary.

Westeros is not a kingdom. It is a geopolitical construct held together by weather, trade, and fear. And none of these, for now, are aligned in favor of unity.

George Friedman is founder and chairman of Geopolitical Futures. He is the author of The Next 100 Years, Flashpoints: The Emerging Crisis in Europe, and the forthcoming Winter Is the Only Constant: Forecasting the Next Century in Westeros.

Note: This piece of writing is a fictional/parodic homage to the writer cited. It is not authored by the actual author or their estate. No affiliation is implied. Also, the Foreign Affairs magazine cover above is not an official cover. This image is a fictional parody created for satirical purposes. It is not associated with the publication’s rights holders, or any real publication. No endorsement or affiliation is intended or implied.

For ‘Games People Play,’ Foreign Affairs invites the finest strategic minds of our era to analyze the enduring conflicts, shifting alliances, and power dynamics that define the multiverse. From the Gamma Quadrant to the Seven Kingdoms, from the plains of Rohan to the Rim Worlds, the logic of statecraft, deterrence, and ambition holds. These dispatches offer sober assessments of real events in real worlds—where borders move, empires fall, and the game, always, is power—and its handmaiden, influence.

Leave A Comment