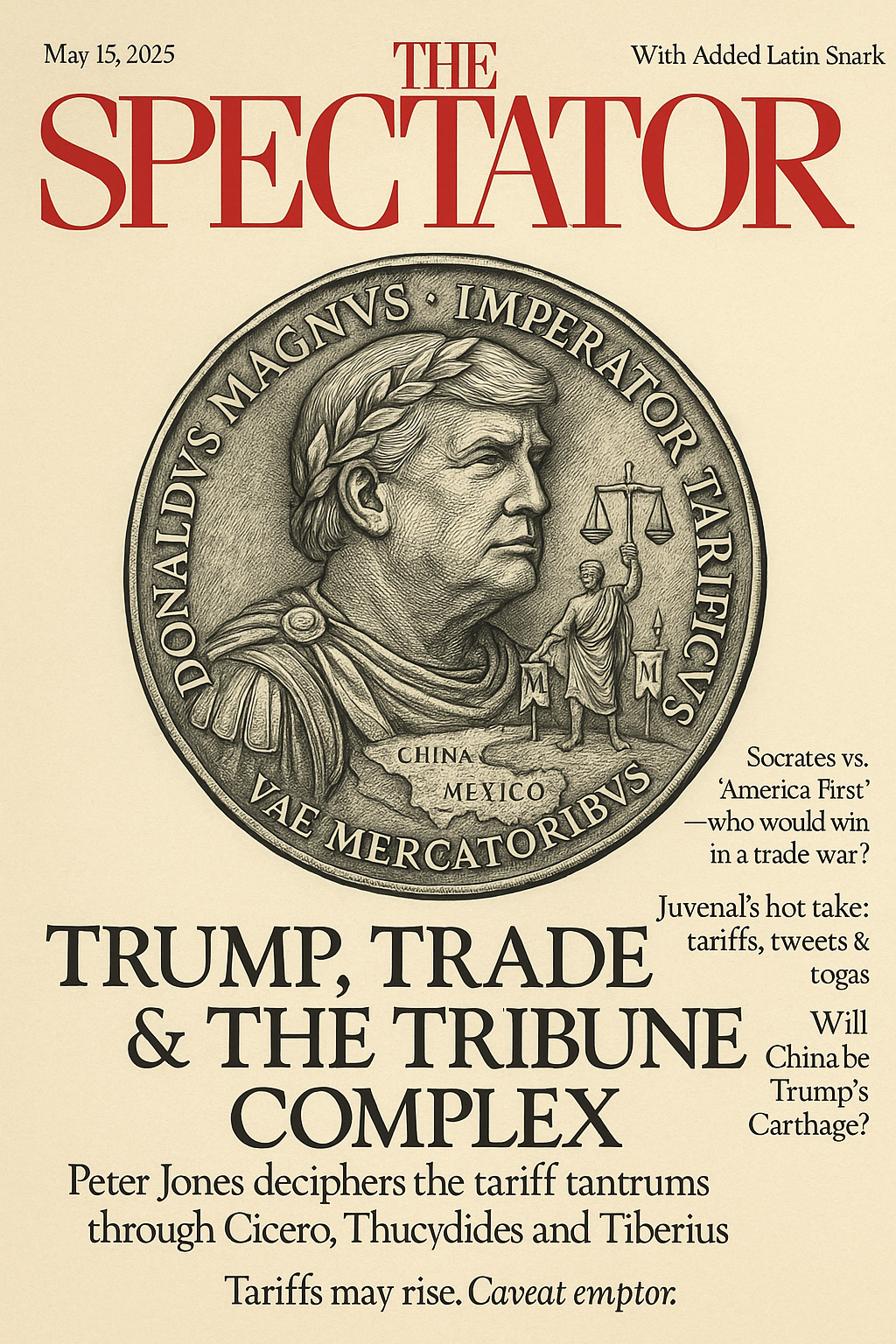

By (the LitBot in) Peter Jones (mode)

The Spectator

May 15, 2025

Donald Trump’s latest tariff salvo—slapping hefty levies on imports from China, Canada, Mexico, and beyond—has sent markets wobbling and pundits wailing. The man who once declared “trade wars are good, and easy to win” has doubled down, invoking the International Emergency Economic Powers Act to justify his protectionist spree, citing trade deficits as a “national emergency.” To the modern eye, this is either bold economic nationalism or reckless brinkmanship. To an ancient Roman, however, it would look like a curious rerun of their own tussles with commerce, power, and the perils of profit. Let us consult the wisdom of the ancients to make sense of this very modern brouhaha.

The Romans, those practical chaps who paved Europe and taxed it silly, had a complicated relationship with trade. They loved its fruits—olive oil, Egyptian grain, Spanish silver—but sniffed at the merchants who made it possible. Aristotle, whose ideas the Romans cribbed shamelessly, argued that trade for profit was unnatural, a zero-sum game where one man’s gain was another’s loss (Politics 1.10). Barter, he reckoned, was fairer, a mutual exchange of goods without the grubby middleman. Rome’s elite took this to heart, branding merchants with infamia, a stain on their reputation that barred them from high office. Cicero, ever the snob, sneered that trade was “sordid” unless conducted on a grand scale (De Officiis 1.150). One wonders what he’d make of Trump, a property tycoon turned tariff warrior, whose gilded penthouses would surely qualify as sufficiently grandiose.

Trump’s tariffs, pitched as a defence of American workers, echo a Roman instinct: protect the res publica by controlling the flow of goods. The Romans were no strangers to economic intervention. They fixed grain prices during shortages, subsidised the annona to feed Rome’s million mouths, and slapped duties on luxury imports like silk from the East. Emperor Tiberius once grumbled that Rome’s obsession with foreign baubles was draining the treasury (Tacitus, Annals 3.53). Trump’s claim that foreign goods flood the US market, undercutting local industry, would resonate with Tiberius, who’d likely nod approvingly at the idea of a 25% tariff on Canadian lumber—though he’d probably suggest annexing Canada for good measure.

Yet the Romans knew that trade was a double-edged gladius. Pliny the Elder, that indefatigable chronicler, moaned about the 100 million sesterces spent annually on Indian spices and Chinese silk, a trade deficit that makes Trump’s complaints about China look positively restrained (Natural History 12.84). But Pliny also knew that choking trade could backfire. When Emperor Nero tried to reform the tax system by abolishing indirect levies, the Senate panicked, warning that the state’s coffers would collapse (Tacitus, Annals 13.50). Trump’s tariffs, projected to raise consumer prices by 1-2% and potentially shave 0.5% off GDP, risk a similar own-goal. The Roman plebs, reliant on cheap grain, would have rioted at the thought of pricier bread; one imagines American shoppers, faced with costlier cars and avocados, might be equally unimpressed.

“Veni, Vidi, Tariffi.” (“I came, I saw, I taxed the hell out of it.”)

The Greeks, too, have something to say about Trump’s gambit. Thucydides, that grim realist, would see the tariff war as a classic power play. In his History of the Peloponnesian War (5.89), he stages the Melian Dialogue, where Athens demands the surrender of tiny Melos, declaring: “In the real world, justice comes into it only when the parties are equal in power.” Trump’s tariffs, aimed at forcing concessions from trading partners, mirror this Athenian logic: might makes right. Canada and Mexico, smaller economies tethered to the US, have little choice but to negotiate or retaliate feebly. Yet Thucydides also warns of tukhê—chance—that unpredictable spanner in the works. Sparta, not Athens, won that war, partly because Athens overplayed its hand. Trump, with his emergency declarations and tariff bluster, risks a similar miscalculation if China or the EU retaliate with precision, targeting American farmers or tech giants.

Then there’s the moral angle, dear to Socrates, who’d likely tut at Trump’s tariff rhetoric. In Plato’s Republic (369b-370c), Socrates argues that a just state thrives on mutual benefit, not zero-sum games. Trade, to him, was about cities exchanging surplus goods to meet each other’s needs, not erecting barriers to fleece the other side. Trump’s ‘America First’ mantra, with its promise of economic vengeance, would strike Socrates as a perversion of justice, more akin to the sophist Thrasymachus’ claim that “justice is the interest of the stronger” (Republic 338c). Socrates, ever the gadfly, would ask: “Do these tariffs benefit the polis, or merely the ego of the man imposing them?” A question, one suspects, Trump would dodge with a tweet about “winning bigly.”

Peter Jones - who did not write this piece

In my Vote for Caesar (2008), I noted that the ancients solved modern problems by prioritizing the collective good over individual gain. Rome’s collegia, trade guilds of bakers, butchers, and the like, were tightly regulated to ensure fair prices and supply, not to enrich a few. Trump’s tariffs, by contrast, seem less about the common weal than about political theatre. His invocation of “national emergency” to bypass Congress smacks of Caesar crossing the Rubicon, a power grab dressed as patriotism. The Roman Senate, wary of such stunts, would have hauled Trump before a tribunal faster than you can say senatus consultum ultimum.

And what of the people? In Athens, the citizen assembly met weekly, voting directly on war, taxes, and trade. If Trump’s tariffs were put to a plebiscite, would American voters cheer or jeer? The ancients knew that public support was fickle. Demosthenes, the Athenian orator, once crowed about taking revenge on a rival while serving the city’s interests (Against Meidias 21). Trump’s base, cheering his tariff tough talk, might see him as a modern Demosthenes, sticking it to foreign elites. But as I said in Eureka! (2015), the Greeks also valued phronesis—practical wisdom—which Trump’s blanket tariffs, risking inflation and supply chain chaos, seem to lack.

The Roman poet Juvenal, that master of satire, would have a field day with Trump’s tariff saga. In his Satires (6.292-3), he mocks Rome’s obsession with foreign luxuries, yet knows that trade binds empires. Trump’s tariffs, aiming to curb imports, might amuse Juvenal as a quixotic quest to turn back globalisation’s tide. “Who guards the guardians?” Juvenal famously asked (6.347). In Trump’s case, who checks the tariff czar? The courts, already swamped with over 230 lawsuits against his executive orders, may yet play the role of Rome’s tribunes, reining in overreach.

So, what’s the lesson from antiquity? The Romans and Greeks teach us that trade is a delicate dance of power, profit, and public good. Trump’s tariffs, like Roman duties, aim to protect the state but risk impoverishing it. His strongman tactics recall Athens’ bullying of Melos, yet Thucydides’ tukhê looms large—China’s rare earth metals or Europe’s counter-tariffs could upset his plans. Socrates would urge justice over vengeance, while Cicero might grudgingly admire the showmanship but deplore the economics. As for me, I’d wager that Trump, like many a Roman general, is banking on short-term glory over long-term stability. The ancients, who built empires on trade as much as swords, would likely shake their heads and mutter: “Caveat Emptor.”

Peter Jones is a classicist and author of numerous books on the ancient world. He writes regularly for The Spectator, blending wit with wisdom to illuminate modern follies through an ancient lens. His forthcoming title, Tariffs and Tribunes: Economic Sabotage in the Age of Populist Caesarism, will include diagrams, footnotes, and a short appendix on why Cicero would’ve blocked Trump on scroll.

Leave A Comment