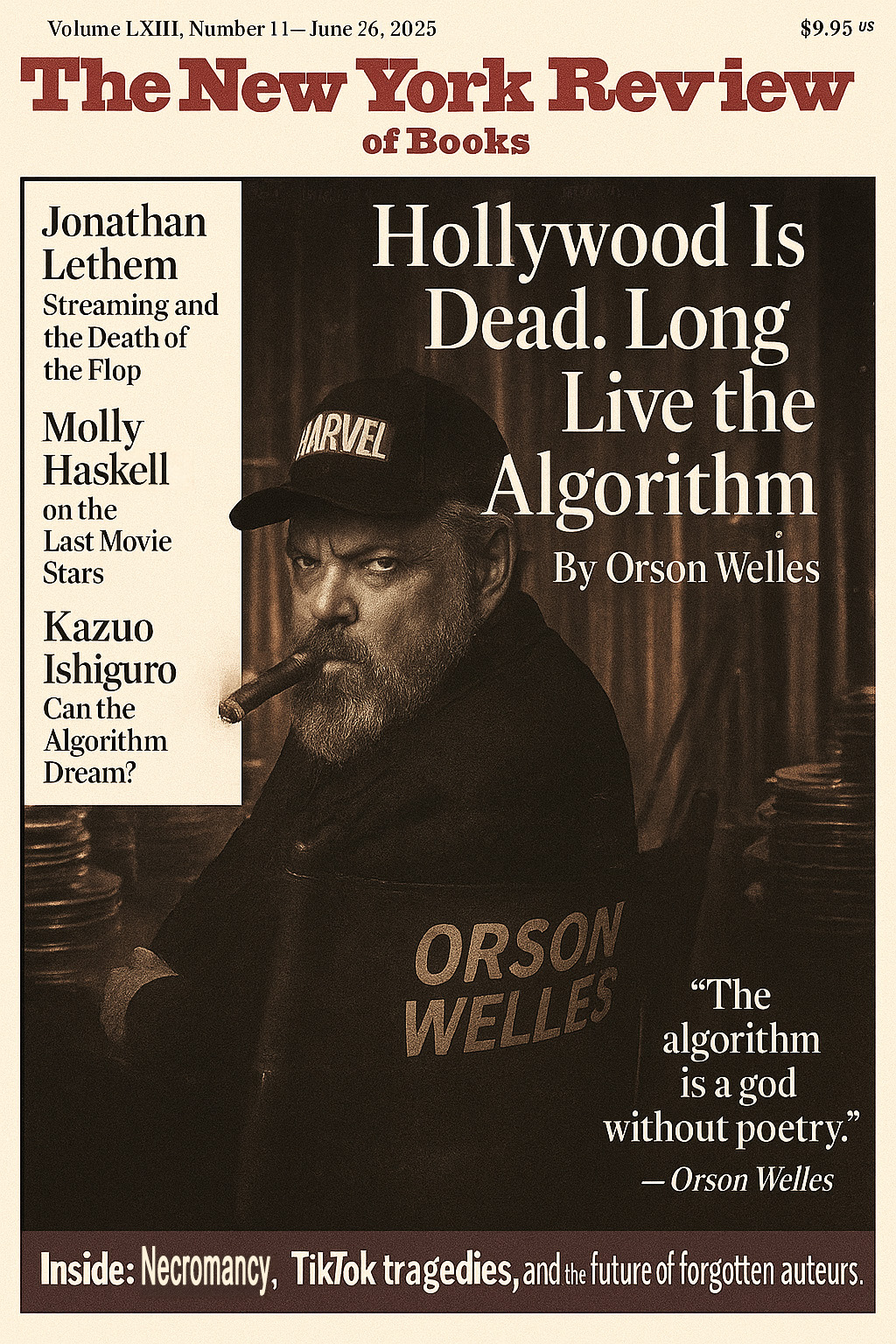

By (the LitBot in) Orson Welles (mode)

The New York Review of Books

June 2025

Let us be frank, since no one else seems willing: Hollywood is no longer a dream machine. It is a vending machine. You insert a query—something about a haunted nun, perhaps, or a talking raccoon—and out pops a content product, warm and twitching, shrink-wrapped in nostalgia and formatted for “global audiences.” We used to call it cinema. Now, the appropriate term might be “asset class.”

In my day—God save us from that phrase—there was at least the pretense that art could erupt amid the commerce. The studios were tyrannical, yes, but their tyranny had a personality. They were petty tyrants with gold watches and bad tempers, not faceless platforms governed by line graphs. A mogul might destroy your film, but he’d do it with flair. With malice. With his own handwriting on the telegram.

Now? The executioner is an algorithm, and it doesn’t even know your name.

HH

I do not pretend to understand how these things work—though I am told it is a little like gambling and a little like necromancy. What I do understand is this: the soul of film is vanishing not in a thunderclap but in a soft whir, the gentle hum of machines sorting metrics. They call it “content strategy.” I call it embalming.

We are governed now by something called “engagement.” This is the altar before which executives and technologists alike grovel. They dress it up with PowerPoint robes, call it “viewer retention,” “brand synergy,” “emotional heat maps.” But make no mistake: it is the same blunt force that once decided which Christians would be fed to lions and which to burning pyres, based entirely on crowd reaction. Bread and circuses, but worse—now the bread is gluten-free and the circus is owned by Amazon.

The algorithm does not dream. It does not weep. It does not feel the sudden tremor of awe that comes when a face half-shadowed on screen utters a line that was never meant for mass appeal. It doesn’t recognize tragedy unless it tests well in Q3. The algorithm is a god without poetry—a deity of metrics, dispassionate and efficient, trimming all excess fat until only the profitable bone remains.

You may think I exaggerate. Very well. Let us examine the evidence.

There was a time when a film could afford to linger. A camera might hold on a woman’s face for a full, aching minute while the light shifted through a Venetian blind. Now, if you do not have a punchline or a decapitation within the first eight seconds, you are told the audience will “bounce.” Bounce? My dear boy, in the 1940s the audience sat. They smoked. They wept. They watched.

Today they scroll.

And what do they scroll through? A soup of capes, sequels, shared universes, and thinly veiled remakes of their own childhoods. Films are no longer made; they are modeled. Characters are not written; they are A/B tested. Narrative is not structured; it is “modular,” the better to be recut for foreign markets, for plane cabins, for phones. Films do not end; they pivot to franchise.

And let us not forget the necrophilia.

Yes, I said it. Necrophilia. I have seen Peter Cushing walk again, long past the point where flesh should permit it. I have seen James Dean cast in a film fifty years after his death, through some infernal wizardry involving pixels and estate lawyers. I have been asked—posthumously, they assure me—to reprise roles I never played. Not in flesh, not in voice, but in “likeness,” that most infernal of legal abstractions.

You see, even the dead are not allowed to rest. Not in Hollywood. Not now. The grave is just another content vault, waiting to be unlocked by the proper licensing deal.

I do not object to technology. God knows I abused enough of it in my time—multi-angle setups, overlapping dialogue, deep focus, optical printers that smoked like chimneys in wartime. No, it is not the tools that offend me. It is the absence of rebellion. The lack of chaos. In a well-run algorithmic system, there are no accidents—and therefore no revelations.

A good film, like a good life, requires deviation. It requires the foolish risk, the badly timed kiss, the unmarketable idea. We did not know Citizen Kane would endure. Frankly, many of us hoped it wouldn’t—we wanted to move on, to make more. We stumbled into greatness because the studio hadn’t yet figured out how to prevent it.

Now they have.

I am told there are still films being made—beautiful, daring ones, somewhere off the algorithm’s radar. Perhaps in Poland. Or South Korea. Or the Midwest. I salute them. I raise a glass of that cheap Hungarian wine I used to buy by the barrel and say, with all sincerity, “Good luck.” Because they are not merely fighting for funding. They are fighting for time. For attention. For a sliver of human stillness in a market that punishes stillness like a sin.

We are drowning in stories, and forgetting how to listen.

When I walk through Los Angeles now (or rather, when I am driven through, as befits a relic), I see the temples of the old gods turned into luxury condos. I see Paramount hedged in by yoga studios. I see men in hoodies with equity stakes deciding the fate of tales that ought to belong to the world. And I think—not bitterly, but with a kind of theatrical resignation—this is what happens when you trade oracles for metrics.

Hollywood is dead, my friends. Not the geography, but the idea. It has been sold for parts. Its bones are ground into trailers, its marrow fed into cloud servers. And in its place stands something else—not a villain, exactly, but a process. And you cannot argue with a process. You cannot charm it. You cannot slap it on the back and offer it a cigar.

You can only watch, and wonder what it would have done with Touch of Evil.

I have always believed that cinema is a kind of conjuring. A séance with shadows. And I fear we are entering an era where no one remembers the ritual. Where the flicker is smooth, the faces are symmetrical, and nothing ever surprises you. You don’t leave the theatre changed. You don’t leave at all. You merely auto-play into the next thing.

But I remain, perhaps foolishly, a romantic. Somewhere out there, a child is watching a grainy black-and-white film on a cracked screen and feeling, for the first time, that ancient tingle—the sudden awareness that these shadows mean something. That they come from a deeper place than data. And if that child picks up a camera, if they dare to disobey the metrics, to displease the algorithm, to linger—

Then maybe all is not lost.

But make no mistake: the machine will not cheer them.

It never does.

Orson Welles is a filmmaker, actor, magician, and reluctant wine spokesman. He directed Citizen Kane at 25 and has spent the succeeding decades dodging creditors, reinventing cinema, and waiting for someone to finish The Other Side of the Wind. He currently resides in Europe, America, and myth.

Note: This piece of writing is a fictional/parodic homage to the writer cited. It is not authored by the actual author or their estate. No affiliation is implied. Also, The New York Review of Books magazine cover above is not an official cover. This image is a fictional parody created for satirical purposes. It is not associated with the publication’s rights holders, or any real publication. No endorsement or affiliation is intended or implied.

Where algorithms go to die and Oscar winners go to Netflix. ‘Screen Burn & Streaming Piles’ is our terminally online film and television salon: part critique, part exorcism. Whether it’s a six-part prestige drama about tax reform or a $200 million reboot of your childhood, we’re here to watch it all burn—frame by frame, pixel by pixel, ego by ego.

Leave A Comment